It’s not a secret that Ukrainians consider corruption one of the country’s main problems ranking higher than the war in the east and economic hardships. But people perceive the problem differently as well as its impact on daily life and own possibility to affect the country’s purification. UCMC collected and analyzed the results of three independent researches, seeking to answer the questions: what don’t we know about the perception of corruption by Ukrainians? How to decrease the corruption tolerance threshold in everyday life? We herewith publish the main findings of the analytical documents.

The methodology: what opinion polls we are referring to

- The public opinion poll on corruption in Ukraine held by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KMIS) and commissioned by the USAID’s Enhance Non-Governmental Actors and Grassroots Engagement (USAID/ENGAGE) program. KMIS interviewed 10,169 persons older than 18 years of age representing entire Ukraine except for the occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

- A research giving an insight on what values people base on when they decide to get to corrupt actions or refuse them as well as on what’s the rationale behind the corrupt actions. The research was conducted by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation commissioned by the USAID’s initiative “Support to Anti-Corruption Champion Institutions Program” (SACCI) using the focus group method. Fifteen focus groups were held in Odesa, Lviv, Sumy, Dnipro and Kyiv regions.

- The research showing how media cover corruption (NOKS Fishes and UCMC supported by the USAID’s SACCI initiative held content analysis of media). The research was made based on the media monitoring in January-July 2018. The overall number of the news pieces on corruption that were analyzed is 4,542; 3,241 of them were released by online media, 998 were broadcast on TV and 285 were published by print media.

Who is responsible for corruption?

One of the paradoxical conclusions revealed by the above researches is that the majority of Ukrainians think that corruption is happening only at the highest political level. At the same time the citizens’ daily participation in corruption schemes goes unnoticed.

The share of respondents convinced that the citizens are one of the three forces responsible for anticorruption action decreased in 2018 to the record-breaking 10,6 per cent (the lowest result since 2007). Many justify bottom level corruption stating that “there are no alternatives”. Personal security prevails as the motivation: 43 per cent of focus group participants claim they were taking part in corrupt acts for personal security. In 39 per cent of the bribe demands take place in the healthcare sector.

Corruption is “them”

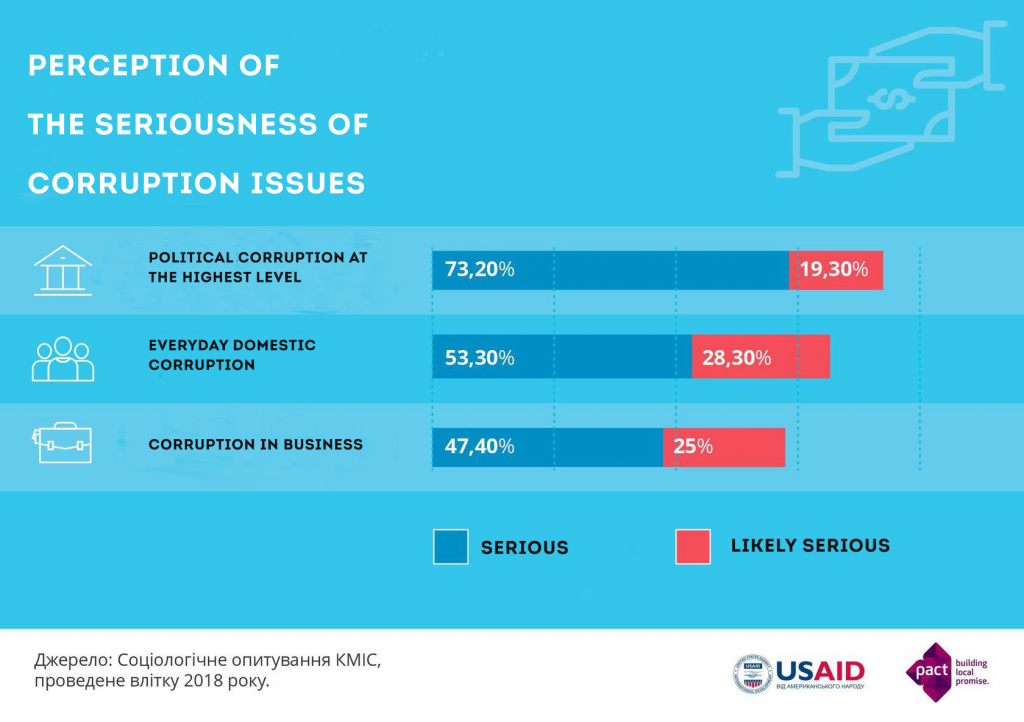

Seventy three per cent of the citizens consider corruption at the highest level a serious problem, 53 per cent take petty corruption seriously and just 47 per cent of respondents are concerned with corruption in business.

Corruption is “them”, the respondents think. Main corruptionists as seen by people are high-level officials. Grand corruption is thus seen as the main problem. Corruption in local self-governance and in business is viewed as a considerably smaller problem.

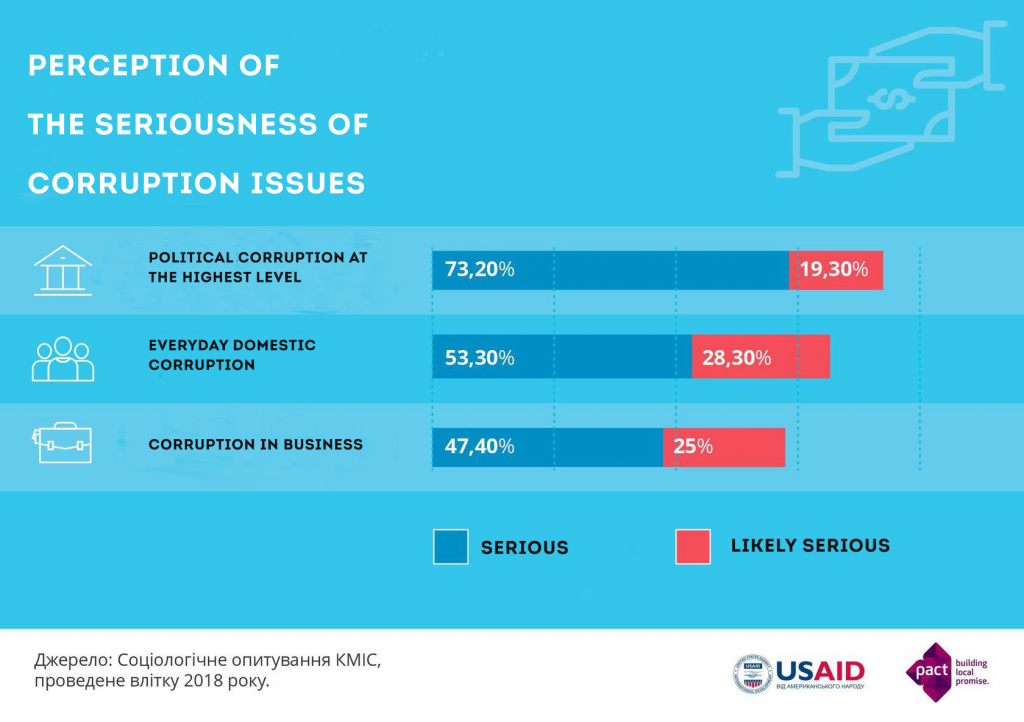

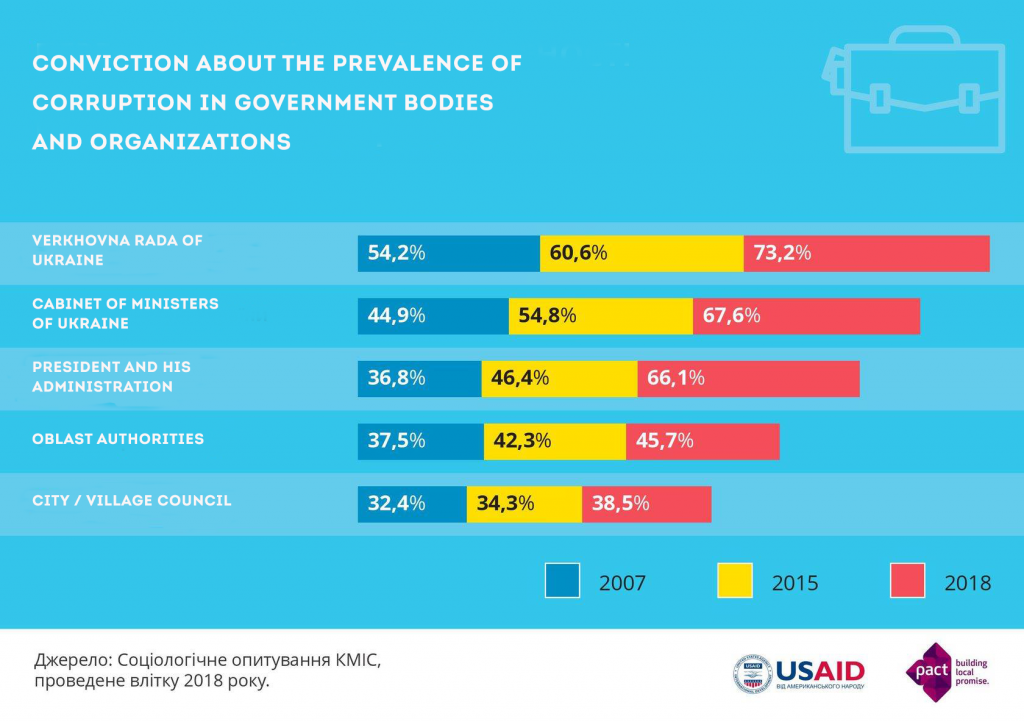

In the last 10 years Ukrainians’ conviction that the highest level of the authorities is corrupt keeps growing.

In 2007 54 per cent were of the opinion that corruption is pertinent to the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine’s Parliament); in 2018 73 per cent are of the same opinion. While in 2007 36,8 per cent thought the Presidential Administration is corrupt, in 2018 66 per cent of respondents share the same opinion.

As the decentralization is unfolding, there is much more money at the regional level today, and it is actively being spent. The level of trust to local authorities is much higher than to the national authorities. At the same time people hold local authorities less responsible for overcoming corruption.

Who is speaking about corruption and how do they speak?

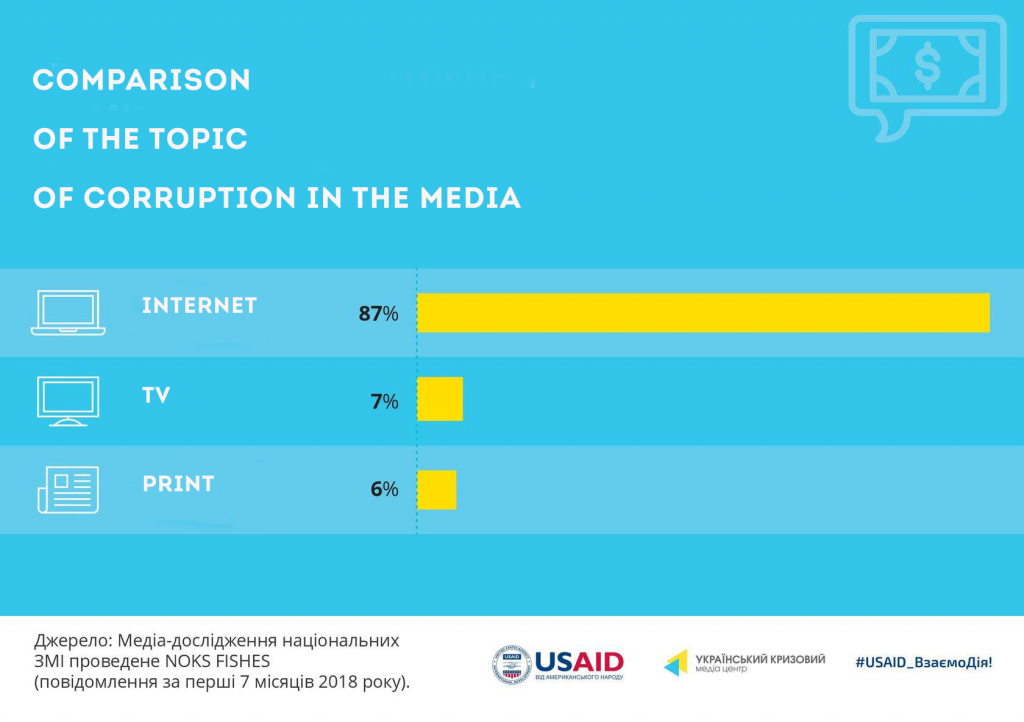

The popular conviction that corruption is somewhere on top can be explained by the fact that 80 per cent of the news pieces analyzed by NOKS FISHES company are about the “institutional corruption”, while 12,7 per cent are not attributed, they just “report corruption”.

Media speak about the problem largely generalizing it, often turning it into a politicized matter that is not related to real life. Eighty seven per cent of news pieces are from online media. Television dedicates less time to the subject (just seven per cent), while the majority of the citizens use it as the primary medium to learn about the news in Ukraine.

What should be done?

Ukrainians are convinced that “a fish rots from the head down”, so that the anticorruption policy striving to meet their expectations needs to include the Hong Kong tactics of “imprisoning three friends”.

However it is not enough to resolve the problem, it also needs to be addressed at the basic level where corruption directly influences the lives of the citizens and where they support it by their own actions.

The researches show that people will give priority to the actions that will guarantee that they will solve their problem of getting a diploma at the university, getting a job, having their child enrolled in a kindergarten or a school, getting a business license, clearing goods at customs, getting healthcare services and so on. If they see that the corrupt way (a bribe, personal connections etc.) considerably increases their chances to solve the problem, they feel nothing that can stop them.

Secondly, they will be saving their time and efforts and sometimes money by taking up the corrupt way. If paying 100 hryvnia (approx. USD 3,7) to a nurse will free them from the need to undergo a long-lasting medical examination, the majority of students will do so.

At the same time if people are granted the possibility of getting a service that is critically important to them quickly and definitely: for example, through the centers providing administrative services (TsNAP) or e-services, and if the possibility is widely publicized, people will be ready to use it and will not be getting to corruption.

It does not mean that corrupt top officials need not be prosecuted and jailed. On the contrary, the inevitability of the punishment is what the majority expects. As long as it’s not there, disbelief grows while politicians and officials are sabotaging positive changes.

On the other hand if the focus stays on grand corruption only, while petty one as well as zero tolerance to corruption is neglected, Ukraine risks creating a system with demonstrative punishment and no real changes.