HBO’s “Chernobyl” miniseries became a true success for its creators. The story of the world’s biggest man-made disaster has appealed to both the audience and the critics – the miniseries has been watched by about a million viewers, it has received lots of reviews internationally. “Chornobyl” (or “Chernobyl” as transliterated from Russian) skillfully reenacts the atmosphere, is dramatic and has an eye for detail so that the Soviet daily routines are recreated with much accuracy. Shortly after it premiered the viewers started discussing how accurate it is in transmitting the spirit of the time and the disaster details.

The miniseries is being watched in Ukraine with particular attention, as there are millions of people who have their own memories of the year 1986. Numerous media have analyzed what is true and what is made up in this film. In 2016, for the 30thanniversary of the disaster, UCMC published a longread on Chornobyl, we now try to figure out what is true and what’s invented in the film.

In try to assess how accurate the film is in relation to the actual events, we’ve used recent testimony of two direct witnesses of the disaster as well as Chornobyl-related books and documentary footage as sources.

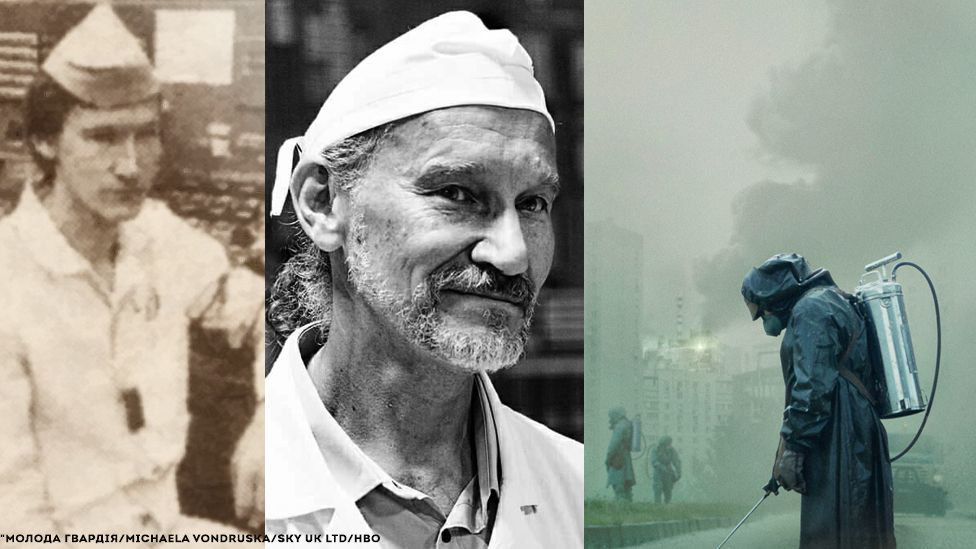

One of the witnesses is Oleksiy Breus. Back in 1986 he used to be a senior reactor operating engineer at the fourth block of the plant. His working place was the control desk seen in the first episode of HBO’s “Chornobyl” miniseries. He took his shift in the morning when the tragedy had already happened. He was interviewed by BBC’s Ukrainian service.

It was precisely Breus, a 27-year-old operator, who pushed the last button on the control desk of the plant’s fourth block. Oleksiy Breus saw and personally spoke to the plant workers who later became protagonists of “Chornobyl” miniseries.

After he was exposed to a considerable radiation dose (120 rem while the Soviet standard at the time was five rem per year), doctors advised him to refuse working at locations exposed to radiation. Oleksiy Breus later worked as a journalist. He is now 60 years old and lives in Kyiv.

Another important testimony is an interview of the senior reactor operating engineer Borys Stolyarchuk who was personally at the control desk of the fourth reactor on a night shift on April 26, 1986. He was a participant of the experiment and witnessed the explosion. Stolyarchuk is one of a few who found themselves at the heart of the disaster and survived. The interview was made by Sonya Koshkina, editor-in-chief of LB for the “KishkiNa” project in November 2018.

We also used as a source the book “Chernobyl: History of a Tragedy” by the Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy, professor of Ukrainian History and director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at the Harvard University in the US. In November 2018 the book published by Allen Lane received the Baillie Gifford Prize, Britain’s prestigious literary prize that rewards excellence in non-fiction writing. Another classic book on this topic is “Chernobyl Prayer” by Svetlana Alexievich, a Nobel Prize winner.

Legasov’s suicide and cassettes in the trash basket – exaggerations on screen

In the opening scenes of the series academician Valery Legasov, a key figure in dealing with the consequences of the Chornobyl disaster, records his testimony of what happened on audio tapes. He takes them out of his house in a trash can and hides them behind the ventilation grill in a bystreet. A KGB (State Security Committee) agent is watching him make all these moves. Being back home Legasov feeds his cat and goes to his room. In the next scene we see his legs hanging above the ground.

The real-life story is a bit different. Valery Legasov did kill himself and left audio tapes without hiding them behind the ventilation grill though. It was not the first time that he attempted suicide. A year earlier, in 1987, he took a lethal dose of sleeping pills but the doctors saved him. The reasons behind the suicide were complex. Legasov became a hero in the West after presenting an honest report on the Chornobyl nuclear power plant disaster. Soviet authorities were not that keen on him: he never got the USSR hero award – a star, despite the fact that the prospect of awarding him had been announced. Moreover one and a half year after the tragedy his colleagues doubted the method used to extinguish the reactor that he had suggested. The scientist was pushed to suicide as his self-esteem was hit and his colleagues did not accept his projects on reinforcing the security of nuclear reactors, suggests Serhii Plokhy in his Chornobyl book. There is a documentary about Legasov “After Chornobyl. Academician Legasov”.

The disaster and radiation exposure of personnel

Exposure to radiation, red skin, radiation burns and steam burns were previously subject to discussion but were never openly demonstrated as they are in the film, says Olexiy Breus, the witness of the tragedy.

“On that day I saw Akimov and Toptunov. They were not in their best form, so to say. It was clear that they were feeling very bad, they were very pale. Toptunov was literally white. They were saying that later at hospital his skin turned black. I saw my other colleagues who worked at night – they were very red.”

“There is an episode in the film, when a person that stayed close to the reactor then comes back and we can see red stains coming through his clothes. It’s hard for me to say if a radiation burn develops that quickly but those whom I saw red simply died then.”

On the first day after the disaster at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant a total of 126 persons were hospitalized, Serhii Plokhy states in his book. What then happens to liquidators suffering from radiation sickness is portrayed in detail including the “invisible” stage when burns pass and it seems that the patient is recovering.

Fire fighters: Chornobyl’s first victims

Firefighters as well as the plant operators were extinguishing fire in multiple locations that night. The film transmits very precisely the story of the firefighter Ihnatenko and his wife Lyudmyla. Lyudmyla’s monologue in which she describes in detail the night of April 26, the trip to a Moscow hospital where she was accompanying her husband while pregnant and the death of the child after the birth, is described by Svetlana Alexievich in her “Chernobyl Prayer“ book.

The funeral scene is also accurate – those dead in the first two weeks after the disaster were buried in two coffins: a wooden and a lead one, then concrete was put over the grave.

At the same time the information on the fire is inaccurate. Oleksiy Breus says: “Everyone heard that there was allegedly a fire on the roof and were afraid that the next block will get caught in fire and that it will spread. But the fire on the roof is a myth. There was no fire, the firefighters and the operators who were there confirm that”.

“There were local fire epicenters and they were quickly extinguished. On the roof there were firefighters who were pouring water into the hot and destroyed reactor with fire hoses. While normally the pumps would supply 48 tons of water per hour, the water supplied by fire hoses probably evaporated without even reaching the target. But this was what they were instructed to do, they were put there and they were extinguishing the reactor.”

“This is what they later died of. These were five firefighters from the emergency unit in Prypiat including Vasyl Ihnatenko. The sixth firefighter who died was Volodymyr Pravik, head of the guard at the firefighting unit of the Chornobyl power plant station.”

“Without lessening their heroism, there is a question left: should the reactor have been extinguished like that?” elaborates Oleksiy Breus.

Divers: those who prevented a bigger disaster

In the miniseries heads of the commission on liquidation of the disaster consequences Professor Legasov and Shcherbina are looking for the people who would get down under the reactor to let the water that accumulated there out of the reservoir. The scene is presented as a search for volunteers who “will die a week after” from exposure to radiation. In real life Oleksiy Ananenko, Valeriy Bespalov and Borys Baranov who accomplished the task and became known as “Chornobyl divers” survived the liquidation. Two of them are still alive, while Baranov died in 2005.

Oleksiy Breus says: “The meeting in search of volunteers portrayed in the film never happened. This work was planned in advance. The decision to let out the water from under the reactor came top down, the governmental commission was tasked to do so, it then tasked the power plant management that in turn tasked Ananenko, Bespalov and Baranov…

They were not volunteers but it does not lessen their heroism at all. Surely, they had neither scubas, nor bathyscaphes. What they wore were plastic diving suits with their heads uncovered.”

“Radiation levels were surely high – much higher than normal, not catastrophic though, they did not get radiation sickness. They ran wherever they could to decrease the radiation exposure”.

Miners: why digging the tunnel?

Another storyline in the series sees miners from Tula dig a tunnel under the reactor that was supposed to stop the advance of the melted part further downwards.

There were concerns that the “lava” inside the reactor will not only enter the reservoir from which the divers were letting the water out but will reach deeper to the ground waters. To stop it they were trying to dig a tunnel to inject liquid nitrogen and catch the lava. It turned out it was unnecessary as the liquid nitrogen was not being supplied anymore.

“The miners did everything and exposed themselves to radiation. Exposure did not happen in the tunnel though that was actually a radiation shelter but when they were out to smoke or to drink water. They were taking off the respirators and undressing but not the way it is shown in the film, not completely…” testifies Oleksiy Breus. Unconvincing is also the scene in which the miners talk to the Minister of Energy.

Watching the disaster unfold and the“death bridge”

In the series a few dozens of Prypiat residents gather on a bridge on the night of the disaster to watch the flare at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant not realizing the risks of exposure to radiation. There was no big flare at night in the first place.

This scene is rather an artistic invention. “I know that people actually went closer to the power plant to see what was happening,” says Oleksiy Breus. “I was in hospital with a guy, a student, who went by bike on the bridge in the morning of April 26. The dose of radiation that he got exposed to, as the professor treating him was saying, caused classic radiation sickness of the first stage. Simply going to see what was on turned to be enough for that.”

“I never heard that people were watching it at night. I guess it is fiction.”

Helicopter that fell is fiction too

Legasov as portrayed in the film upon coming to Chornobyl suggests extinguishing the reactor with a mixture of sand and boron. He counted that five thousand tons of the substance will be enough, it was decided to disperse it with helicopters from above. The series show one of them flying above the active zone and falling into the reactor after radiation made its equipment fail.

What happened in reality is Legasov did invent the way to put out the reactor but the substance also included lead. The helicopter scene is fiction – it did fall but in October 1986. The helicopter was supposed to pour water on reactor’s roof to cut the dispersal of the radioactive dust but its blades got trapped in the rope of a crane and the helicopter fell near the reactor.

Anatoly Dyatlov is less of an evil than in the miniseries

In the series action at the nuclear plant starts immediately after the disaster happens. A clearly negative protagonist is presented to the viewers – deputy head of the plant Anatoly Dyatlov. His aim is to experiment with the emergency stop of the reactor and he’s got personal ambitions. When explosion occurs, in the film Dyatlov blames it on the explosion of the cooling reservoir. Plant management holds on to the same version and demands to supply water to cool the reactor’s core. He also orders the interns to manually bring the rods into the reactor’s area to stop it.

In reality as Plokhy explains in his book, Dyatlov never insisted that it was the cooling reservoir that had exploded. Senior reactor operating engineer Borys Stolyarchuk also says there were no serious discussions between the staff. In his interview to KishkiNa Stolyarchuk reassures that it was not the actions of the personnel that caused the tragedy but reactor’s imperfect structure. He also says that Dyatlov and his colleagues were tried because all the responsibility was attributed to them.

A year after the explosion, during the trial of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant management Dyatlov acknowledged that he failed to resume the reactor’s work after a sudden output fall. According to his version the main reason for the disaster is reactor’s imperfection.

“The film conveys very well the emotional mood that both the personnel and the authorities then had. Indeed, no one knew how to act. We, operators, the plant’s management, officials, Gorbachov – no one knew, nothing similar had ever happened before. It is ok for such situation, one needs time to figure out what happened and how to act on it,” Oleksiy Breus says.

“As to the personality of the key figures of Chornobyl disaster, like director Bryukhanov or chief engineer Fomin, deputy chief engineer Dyatlov, what we see in the series is not fiction but mere lies,” he claims.

“Their characters turned to be absolutely twisted, they are portrayed as pure evil. In fact they were not like that. I guess Dyatlov who was in charge of the tests that night on April 26 at the fourth block became the main anti-hero in the series because it is the way he was seen by many plant workers and operators shortly after the disaster. It was a quick conclusion, the opinion then changed.

He indeed was a very strict person, people were afraid of him, when he showed up at the block everyone felt uncomfortable. However Dyatlov was a highly-qualified professional… and the reason for the disaster to have happened was not his authoritarian style but the reactor’s drawbacks,..” Breus says.

Dyatlov died of infarction in 1995, his version of the events is available in the video.

***

There are enough inaccuracies in the series but screenwriters paid much attention to details recreating photographically accurate shots: a convoy of white-and-blue buses evacuating the residents out of the exclusion zone, divers going under the reactor, the reactor in flame. Even though “Chornobyl” doesn’t have the 100-per-cent accuracy from the documentary standpoint it is made with big respect to the tragedy’s victims and big attention to detail. The series also led to the increase of interest to documentary testimony and historic research of the tragedy.