Soviet propaganda was long claiming that Stepan Bandera, Roman Shukhevych and all OUN(b) members used to be agents of Gestapo, SS, SD or Abwehr and were just taking orders from these services. What was the actual state of play?

UCMC publishes a translated short version of the original Ukrainian-language article by Novoe Vremya. The author of the original text is Ihor Bihun of the Center for Research of the Ukrainian Resistance Movement.

The Myth

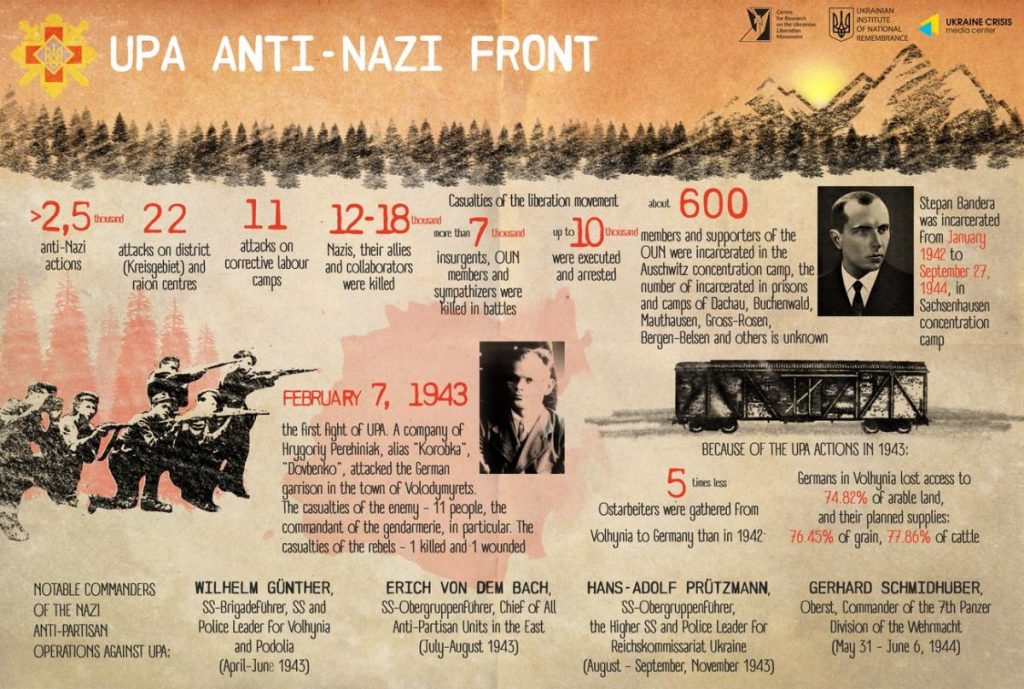

Stepan Bandera, Roman Shukhevych and all members of OUN(b) (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) were agents of Gestapo, SS, SD (intelligence agency of the SS and of the Nazi party) or Abwehr (military intelligence organization). They were accomplishing the orders of these services. The Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) was established by the special services of the Third Reich and was fighting alongside Hitler supporters.

Facts

The myth originates from the incorrect understanding of events that relate to the period of time when the OUN was cooperating with the Nazi Germany in the 1930s – in the beginning of the 1940s. OUN started cooperating with Germany for geopolitical reasons – as Germany was a traditional opponent of Poland.

Back in the 1920s the Ukrainian military organization (UVO) was in touch with intelligence of the democratic Weimar Republic. As the Nazi came to power Germany became the biggest country on the European continent (except for the USSR) that was most actively pursuing the intention to change the Versailles system. It coincided with the intentions of the OUN as the countries – winners of the World War I could not map independent Ukraine. Ukrainian nationalists considered Germany as an ad-hoc ally.

Relations between OUN and Germany were not smooth. After the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact was signed in 1934 OUN leader Yevhen Konovalets moved from Berlin to Switzerland. The same year Germany passed to Poland active OUN participant Mykola Lebid who was hiding there after OUN attempted the life of the Polish Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki. Finally, contrary to what the nationalists expected, Hitler agreed to the Hungarin occupation of Zakarpattia and to the Soviet occupation of the Western Ukraine. Germany was severely criticized by Ukrainian clandestine publications, for example, by Pozbudova Natsii (“Development of the Nation” – UCMC) magazine. OUN’s relations with Lithuania, who was Poland’s enemy as well, were much better.

However, Germany remained the only real power capable of challenging Poland and the USSR, that’s why after the split of OUN (into OUN(b) headed by Stepan Bandera and OUN(m) headed by Andriy Melnyk – UCMC) both the supporters of Bandera and of Melnyk continued cooperating with Germans.

OUN(b) had managed to set up the military training system for the members of its organization using its contact with Abwehr and with some generals who sympathized with the Ukrainian Resistance Movement. Ukrainian nationalists were able to get trained in the German occupation zone of Poland alongside security units at factories, workers’ units and police schools in exchange for intelligence information they were providing. Moreover the organization established a network of military training courses not dependent on the Germans. These courses were attended by all its members including Stepan Bandera.

In February 1941 Bandera reached an oral agreement with the chief of the Abwehr admiral Wilhelm Canaris and the commander of Wermacht’s ground forces Walther von Brauchitsch as to the creation of the Ukrainian legion. Two battalions – Nachtigall and Roland were created from OUN members. They were supposed to exercise subversive and reconnaissance activities. Instead when the war started Nachtigall’s functions were limited to providing security at the strategic infrastructure objects, while Roland did not take part in the combat actions at all.

Moreover, Nachtigall’s commander from the Ukrainian side was Roman Shukhevych. When his battalion was being formed, its fighters refused to swear loyalty to Germany and instead swore loyalty to Ukraine only.

In August 1941 after repressions against the nationalists related to the Declaration of Ukrainian State Act started the Nazi reorganized Nachtigall and Roland. The Germans reorganized part of the battalion’s personnel into the 201st police battalion that was safeguarding the Nazi base positions and counteracting the Soviet partisans in Belarus between March and December 1942. In contrast to Nachtigall and Roland, the setup of the 201st battalion was not agreed with OUN(b), Ukrainian combatants were enlisting in it not to get arrested.

On December 1, 1942 battalion fighters refused to continue their service. Then the Nazi dissolved the unit and arrested the officers. Shukhevych was arrested but succeeded to escape, he became the military “referent” (responsible for military training) of OUN(b) and later became the head of the organization.

One needs not overestimate the importance of cooperation between OUN(b) and Abwehr. As a rule Abwehr was recruiting OUN members individually, while the command of the OUN was making use of it and was giving the agents tasks of their own. The nature of these ties was pragmatic and ad-hoc, when both sides were only pursuing their own benefits without any political implications. In April 1941 Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller said to his colleague from SD Walter Schellenberg that “Ukrainian nationalistic leaders are moving to their goals in an uncontrolled way.”

Right after the German offensive on the USSR on June 23, 1941, OUN(b) sent to the Reich Chancellery a memorandum on how the Ukrainian issue should be resolved after the dissolution of the USSR. The document said: “Even if the German troops after they enter Ukraine will surely be greeted as liberators, the situation might change soon if Germany comes to Ukraine not for the purpose of restoring the Ukrainian statehood and not with the mottos expected.” Already at that point Bandera supporters foresaw a possibility of the anti-German armed resistance should Germany take an unfriendly position towards Ukraine’s independence.

Thus, despite the military cooperation with Germany OUN(b) was pursuing their own political line that the Nazi were not aware of. A good example of such behavior was Declaration of Ukrainian State Act of June 30, 1941 in Lviv. It came as a surprise for Hitler’s supporters as independent Ukraine was never part of the Third Reich’s plans. On July 5, 1941 the Nazi arrested Bandera, on July 9 – head of the newly established government Yaroslav Stetsko.

In July-August the occupants were pushing on OUN(b) so that they call back the Act of June 30. However, Ukrainians firmly refused and were sent to prison in Berlin. Between September 15, 1941 and the end of the same year the German punitive agencies arrested about 1,500 Bandera supporters. On November 25, 1941 the security police issued an order to arrest and execute the activists of the “Bandera group” who “were about to stage a riot in the Reich Commissariat Ukraine aiming at establishing an independent Ukrainian state.”

The military training delivered by Germans became later of use during the anti-German fight that OUN and UPA were conducting through 1942-1944. Many veterans of Nachtigall, Roland and of the 201st police battalion became part of UPA as instructors or military commanders. Personnel of the first UPA Staff including chief commander Vasyl Ivakhiv, chief of staff Yulian Kovalsky and aide-de-camp of the staff Semen Snyatetsky got killed in combat with the Germans on May 13, 1943. The last two were former Nachtigall officers.

It is unlikely that the agents and puppets of the special services would be fighting against their leaders and sponsors. Seeing OUN(b) command as agents or as those who were accomplishing the orders of German special services without any hesitation is not correct. OUN had their own logic of fighting, the ultimate goal of which was an independent Ukrainian state. All efforts including military cooperation with the Germans were set to achieve this task. OUN was hiding their plans from the Nazi. That’s why the Declaration of Ukrainian State Act of June 30, 1941 became a moment of truth in relations between OUN and Germany.

It became obvious that the German Nazi and the Ukrainian nationalists were actually enemies.