Photo credits: UCMC and the Administration of the President of Ukraine. Go back to reading.

On March 15th Nataliya Popovych, co-founder and board member of Ukraine Crisis Media Center, and Oleksiy Makhuhin, Head of Hybrid Warfare Analytical Group of Ukraine Crisis Media Center testified before the Special Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods of the Parliament of Singapore. The lessons learnt by UCMC in the four years of serving on the frontline of the information warfare and defending Ukraine’s interests against the Russian aggression were shared with the honorable members of the committee and will inform Singapore’s policies to tackle the challenges of hybrid warfare against sovereign states. The write up is below and in the attachment. UCMC thanks the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Ambassador in Singapore for facilitation.

In the last four years, Ukraine has experienced first-hand the undermining effects of massive foreign-based fake news attacks that were aimed at destabilizing and manipulating public opinion at home and internationally and weakening of the national dialogue within the Ukrainian society. Non-governmental organization Ukraine Crisis Media Center (UCMC), which was created in March of 2014, has become one of the first civil society organizations in the post-Revolution-of-Dignity Ukraine that started identifying and drawing public attention to information distortions, misrepresentations against Ukraine revealing the cases of deliberate misinformation that were produced and disseminated both nationally and abroad.

Serving as an independent media platform for the journalists, public activists, key opinion leaders, civil servants and volunteers UCMC has had a unique opportunity to analyze in-depth the intricacies of miscommunication between the actors and vulnerabilities that were professionally exploited by the anti-Ukrainian elements. UCMC started producing its own content including visual, infographics, Op-Eds, etc., for international as well as the national audience to better explain what was happening in Ukraine and Crimea at the time. The system of fake news, troll attacks and propaganda disseminated by Russia was so massive that conventional means of only countering them were ineffective. We understood that this challenge requires a comprehensive response and approach from Ukraine, one that would address the day-to-day information crises, but also be able to enhance the role and responsibility of journalists and social media users, improvement of communications on behalf of the government institutions, providing training opportunities on strategic communications to government agencies and civil society, and advising both on information policy and national resilience-building strategies. UCMC was able to engage international donors to implement many of the above-mentioned efforts with a degree of success that is possible given that Ukraine is a democracy. The most profound success has been achieved in building the national identity and resilience, as well as establishing and streamlining communications efforts in the security and defense sector of Ukraine.

UCMC operates through a number of teams and task forces, including the press center, international and national outreach, hybrid warfare and security analytical group and others. UCMC is a non-governmental and a non-profitable organization which is not linked to any political party. It maintains an independent editorial policy on the topics of research or analysis its units work on or the experts it promotes via press briefings, seminars, conferences or roundtables, etc. UCMC develops its own content and provides a platform for analysis and communications of its partner organizations benefiting both the experts and the wider public. Its events provide a platform for dialogue amongst politicians, experts, journalists, businesspeople, and students.

Since Russian direct military intervention in Ukraine in 2014, our country has been actively fighting against Russian disinformation, informational operations (IO), various falsehoods and fakes, hostile narratives, as well as military, economic, diplomatic and political actions defined under the term of hybrid warfare. Now we understand that the hybrid warfare against Ukraine (by the Soviet and then post-Soviet Russia) started decades before, with only the most recent hybrid attack attached to the new doctrine of the Russian leadership. In 2006 Russian President Putin officially introduced new ideological platform, known as “Russkiy mir” (the Russian World or Pax Russica). Its greatest ambition was the recreation or re-establishment of the Russian Empire in accordance with the borders of the former USSR. Russia also declared that its duty is to protect all compatriots of “Russkiy mir”, which were defined as all Russian-speaking people, not only in Russia but also abroad. In April 2007 Putin said, “The Russian language not only preserves an entire layer of truly global achievements but is also the living space for the many millions of people in the Russian-speaking world, a community that goes far beyond Russia itself.” Although most of the world leaders back at the time reckoned that Putin implied harmless cultural diplomacy, the ensuing military aggression in Georgia in 2008 and in Ukraine in 2014 proved they underestimated the threat.

Ukraine’s painfully learned lesson in 2014 has become to counter all risks and threats emerging from soft power policy of aggressive countries by strengthening the resilience of Ukrainians in their pursuit of progress and well-being for Ukraine and contributing to the efforts of Ukraine’s allies in defending the values of the free world shared by Ukrainians. Ukrainians began to notice vulnerabilities that may be contained in language issues, culture, religion and history and reflect on how they should be prioritized as they are used as main pretext for informational (and, subsequently, military) attacks. As formulated by a Soviet historian M. Pokrovskiy “History is politics targeted at the past”, and as such the war Russia initiated on Ukraine in 2014 cannot be understood without delving into history.

Even though Moscow and Russian state emerged centuries later than the medieval state of Kyiv Rus which is the cradle and capital of modern Ukraine, the Russian empire has dominated different parts of Ukraine for centuries and has worked to systemically exterminate the Ukrainian language, traditions and people before. In 1932-1933 Moscow-based Communist regime initiated Holodomor, a man-induced Great Famine, which killed minimum 4 mln Ukrainians. According to Anne Applebaum’s recent work titled “Red Famine”, there is no doubt that Stalin’s decision to impose such inhuman policy on Ukraine was ethnically targeted. He perceived Ukrainians to be advocates of freedom and individualism which was against the values of communist ideology around which the USSR was built. Ukrainians were labeled as a threat. Ukraine happened to be at the core of the Russian version of the history of our region, and part of the Russian national idea to the extent that many Russians till today genuinely believe that Ukrainians do not exist. Only for a brief moment, right after the breakup of the Soviet Union and in the massive wave of democratization of the republics of the former Soviet Union, that the world trusted Russia’s democratic future enough to make it one of the nations-guarantors of Ukraine’s sovereignty in the Budapest Memorandum. According to the memorandum, Ukraine gave up its vast nuclear arsenal to contribute to the non-proliferation of the nuclear weapons and for peace in the world. But ever since Putin, only years later, declared that “the breakup of the Soviet Union was the biggest geopolitical catastrophes of the 20th century”, it was clear that again – neither in the Russian history nor Russia’s aspirations of the future there is a place for a sovereign and independent Ukraine.

At the same time, Ukraine, ever since regaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 has never defined Russia as its existential threat. The country has not undergone any significant de-russification or de-communization or worked to recover from any post-genocidal syndromes. Its economy and politics have soon become dominated by the post-communist elites and oligarchic groups controlling vast sectors of the economy. In this way, till 2014 there have been numerous vulnerabilities which Russia has continued to exploit: the language issue, infiltration of the Ukrainian economy through financial capital, natural resources, in particular, gas dependence, cultural diplomacy, corrupted political landscape etc. 2014 became the turning point because slowly but surely the Ukrainian society was becoming stronger even as a former post-colonial nation and drifting towards European community. When Russia-backed President Yanukovych refused to sign the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, Ukrainian rose to the biggest protest in the modern history – Revolution of Dignity. It weakened the country, as in the aftermath of the revolution, Russia used its strength to attack and annex Crimea. But the Revolution has strengthened the backbone of the Ukrainian identity and created a ground for the resilience of Ukrainians towards the war and further influence from Russia.

There are many different classifications of strategies countering informational interventions. We believe one of the most descriptive is the one suggested by M.C. Libicki. He identified two major strategies: “Castle” and “Market”. “Castle” puts all efforts into not letting in anything foreign, while “Market” is fundamentally open to all foreign and progress by embracing and processing of new information. It is easy to sort key world states by this criterion. On the rhetorical level, it is usually represented through narratives of Stability vs. Progress. That is to say, closed (stable) states assess win as a failure of opponents, while open (progressive) states assess win as cooperation. Russia is an example of a “castle” society, in which the state prevails over the individual, stability is treasured more than progress (this is one of the reasons Russia has not modernized in its essence for centuries) and for which a win-win approach is not acceptable. If Russia does not win, it loses, and losing is not an option to the current leadership of Russia, nor to its people.

One also has to take into account that according to RAND research by Rand Waltzman Russia has a very different view of Informational Operations (IO) than the West in general. For example, a glossary of key information security terms produced by the Russian Military Academy of the General Staff contrasts the fundamental Western concepts of IO by explaining that for the Russians IO are a continuous activity, regardless of the state of relations with any government, while the Westerners see IO as limited, tactical activity only appropriate during hostilities. In other words, Russia considers itself in a perpetual state of information warfare, while the West does not. This makes the West so vulnerable to systemic influence from Russia, as we have seen in the elections of the US President, the French elections, and Brexit campaign.

In February 2017, Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu openly acknowledged the formation of an Information Army within the Russian military: “Information operations forces have been established that are expected to be a far more effective tool than all we used before for counter-propaganda purposes.” The current chief of the Russian General Staff, General Valery Gerasimov, observed that war is now conducted by a roughly 4:1 ratio of nonmilitary to military measures. In the Russian view, these nonmilitary measures of warfare include economic sanctions, disruption of diplomatic ties, and political and diplomatic pressure. The Russians see information operations as a critical part of nonmilitary measures. They have adapted from well-established Soviet techniques of subversion and destabilization for the age of the Internet and social media.

State-sponsored propaganda and disinformation have been in existence for as long as there have been states. The major difference in the 21st century is the ease, efficiency, and low cost of such efforts. Because audiences worldwide rely on the Internet and social media as primary sources of news and information, they have emerged as an ideal vector of information attack.

R. Waltzman says that the most important from the U.S. perspective, Russian IO techniques, tactics, and procedures are developing constantly and rapidly, as continually measuring effectiveness and rapidly evolving techniques are very cheap compared to the costs of any kinetic weapon system and they could potentially be a lot more effective.

Nowadays informational battlefield is virtually not limited. But fighting with fakes and falsehoods is not only a war with their industrial distribution. From our experience, it is first and foremost about strengthening the resilience of the people to fakes and falsehoods in the first place, as fakes rely on the strength of the weak (people) (G. Pocheptsov). Disinformation is organized in narratives, which we suggest considering as key structural elements of disinformation campaigns. Once established narratives are supported by fake news in smaller part, but mainly by deliberately manipulated interpretation of real events. These narratives keep the attention of target audience in the desired frame and are more sustainable comparing to just fake news because even when countered by arguments they do not fail.

The tactics of offensive disinformation campaigns can be broken down into the following stages.

- Identify major target groups by the most basic and rooted characteristics (nationality, age, sex, church, race, language, income) (For example, in Ukraine all Soviet, often Russian-language, migrants into Ukraine, especially with predominant place of living in the South and East of Ukraine, Russian Orthodox Church parishioners in Ukraine may be easily exploited, LGBT community or foreigners living in Ukraine may be manipulated by Russia-backed provocations, pensioners as a vulnerable category to economic conditions and poverty may be manipulated etc.);

- Design map of distribution channels and plan to ensure superiority there (for example “Russkiy Mir” was promoted since 2006 by PR companies and information campaigns for both internal and external Russian-speaking audiences through mass media, social media, and in Russian popular and scientific literature, especially historical, political, economic journals etc. Also, two massive international media channels “RT” and “Sputnik”, as well as Ruptly, were launched);

- Design and distribute overarching narratives that “explain” fundamental reasons of the conflict (for example, “Russia and Ukraine is one nation separated by the West in attempt to weaken Russia” or “Russia is attacked by the West because it fights for multipolar world order”);

- Design and distribute more specific local narratives (for example “Leadership of your army has betrayed you” or “You shouldn’t even try to fight against our army, because it is much bigger”);

- Support narratives with emotion, image/picture, and “proofs” or explanations – doesn’t matter if all are false or manipulated (when using deliberate falsehood make sure that information is outsourced);

- Leverage local opinion leaders, also known as “useful idiots” among the local academia, think tanks, politicians, community leaders to advance the narratives and make them feel as “own”;

- Monitor, measure the result and adjust the messages.

Negative news is spreading much faster and reaching a wider audience than positive. Recent study by Reuters Institute and University of Oxford on Measuring the “reach” of fake news concluded that despite clear differences in terms of website access, the level of Facebook interaction (defined as the total number of comments, shares, and reactions) generated by a small number of false news outlets matched or exceeded that produced by the most popular news brands. Fake news can be compared to “junk” food, as they are much easier (and cheaper) to take & go. Nevertheless, fakes won’t have any power in the media world, unless they fit into powerful narrative and fall onto a weak or unprepared ground.

In case of Ukraine, during almost two years we worked to consult different state authorities on strategic communications. During those years a number of resilience-building campaigns were developed and introduced to strengthen the Ukrainian identity and make it better prepared to Russia-backed provocations, fakes, and misinformation. As part of de-communization, a new state calendar of official holidays and state commemorations was developed. It included, for example, the efforts to help Ukrainians draw more reflections and lessons from our history, for example:

- Kruty Campaign which marked a heroic defense of Kyiv before Bolsheviks in the Russia-Ukraine war of the 20s of the 20th century;

- reemphasizing the tragedy of the Second World War, in which over 6 mln Ukrainians died (in military formations and civilians) vs the Russian narrative of glorifying the Red Army and neglecting the number of victims who suffered in the process;

- creating new date and tradition to commemorate the Defender of Ukraine – on October 15th, which is historically a date aligned with the history of the Ukrainian Cossack state of centuries before

- highlighting commemoration of Holodomor as the tragedy which Ukrainians should never allow to happen again, neither against the Ukrainian people nor in principle and many others.

Other campaigns included new ways to commemorate the memory of the Heavenly Hundred, those 116 civilians who gave their lives in 2014 for the free and European future of Ukraine.

Steps to defend the Ukrainian information space on behalf of the state included a law on quotas for the Ukrainians language content and music on TV and radio, prohibition of the Russia-own social media networks etc. As the result of the latter, Russia-owned websites lost their dominant position. Their number in the top-10 went down from five to three, and for the first time in years, Facebook became the most popular social network in Ukraine (instead of Russia’s VKontakte). The use of Russian sites is still possible due to VPN. Nevertheless, using it requires bigger effort from the user and keeps away those who were not aware that they were using Russian networks (like many soldiers), which was the primary goal of the ban.

All of the above-mentioned efforts on the back of the real war and its consequences in the shape of victims, veterans, losses from which Ukraine is suffering has led to a continuous strengthening of the Ukrainian identity.

According to the research “The Ukrainian society and European values” conducted by Gorshenin Institute in cooperation with Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Ukraine in November 2017, over 92% of people living in Ukraine consider themselves Ukrainians and only 5,5% – Russians. The younger the respondents, the more often they identify themselves as Ukrainians. In the western part of Ukraine, the Ukrainian national identity was declared by 98,3%, in the northern – 94,8%, in central – 94,2, in the southern – 84,6% and in the eastern – 84,6%.

Also, the attitudes of the Ukrainians towards the EU and NATO, which highlight the shared values and a common understanding of the collaboration around values have become stronger. According to the Kyiv International Sociology Institute’s recent research, 57% Ukrainians support Ukraine joining EU and 62% Ukrainians support Ukraine joining NATO.

But Ukraine has no means to influence what Russia is preparing its own population for.

In our recent research of newscasts and political talk-shows at top three Russian TV channels during the period of 2014-2017, we have learned that Russian media constantly create narratives about the EU that are often not based on important events. As a result of it Europe is mentioned 17 times every day in negative context just at the researched channels – compare to “only” six daily ads of such top of mind brand, as Coca-Cola at the same channels. Another demonstrative fact is the average ratio of negative to positive news for all European countries – it is 83% for negative. However, there are only two countries with this ratio at 60% for positive and they are Belarus and Switzerland. Both countries Kremlin sees as partners, though for different reasons.

Russian media fundamentally changed the whole paradigm of news: facts and events are used to support the already prepared narratives (please refer to the chart below). That’s why top channels have similar news agenda.

90% of all the researched above negative coverage may be divided into six main narratives. 43% of negative news belong to alleged insecure and unstable life in Europe. According to it daily life in Europe is difficult, dangerous and unstable. To “prove” this Russian media constantly select minor, insignificant problems of European countries, while real issues are heavily exaggerated. Thus Kremlin is building up “stability” as the most important value worth degradation in most other spheres.

We reckon that tremendous resources that Kremlin puts within these narratives create the following threats for Europe:

- Convince of Russian population never to accept European liberal values, neither today nor tomorrow.

- Get Russian population ready for potential conflicts with the West and feel right and motivated to take over the weak and divided Europe.

- Increase awareness, that if Russia isn’t resistant, Europe will impose their “toxic” values.

The research findings are a call to action on behalf of the research countries to better understand the gaps in attitudes between a given nation and how it is perceived by the Russian population, research thoroughly the level of infiltration by Russia into the local economy, information space, resources etc. and determine a respective strategy.

An example:

Our analytical group was involved in Ukrainian military strategic communications in the period of 2015 – 2017. At the beginning of that period, Russia used various tailored narratives against the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Here are some of them:

- The leadership of your army is weak. It must be fired.

- Conditions of service in your army are terrible.

- Your President betrayed you in Minsk negotiations. He and his generals are traitors.

- West doesn’t care about you. You are doomed.

- You can always escape from the army going to Russia or Donetsk.

- Don’t let yourself be fooled by your illegal government.

The above narratives were also supported by informational operations, like demoralization of soldiers through threatening personal messages; recruiting to rebel groups in Russian social networks (VKontakte, Odnoklassniki); providing free WiFI to our soldiers at the front line in order to steal their personal information, etc.

Altogether, the Russian propaganda resulted in 62% negative coverage of the Ukrainian military leadership in the Ukrainian media and trust to the Army was at its low.

To counter Russia’s disinformation campaigns, the following had been done:

- NGOs got a mandate to become an engaging chain between the State, including the Army, and the Society (Civil society trusts to NGOs).

- The military commanders from the front line at the battalion and brigade level spoke openly on Ukrainian TV channels.

- A pool of credible speakers was created within the Army.

- The Chief of Armed the Forces came into the spotlight with regular information sessions for the media.

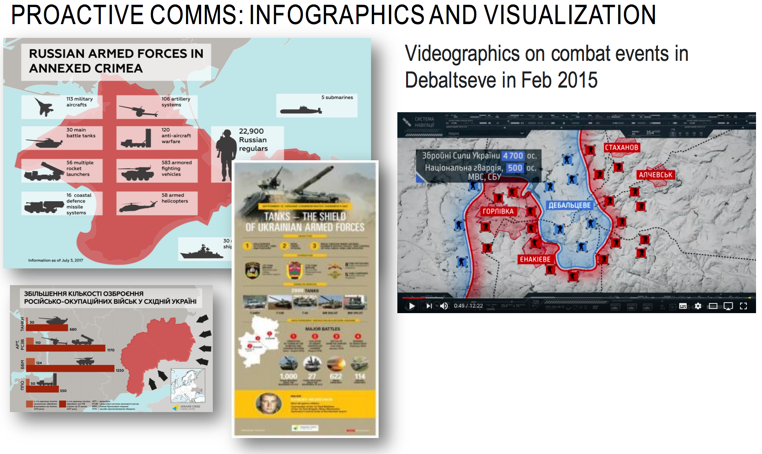

- A decision was made to make information about the Russian Army units location and their captured soldiers and officers public – support with explanations easy to comprehend (see below).

- The launch of several advertising campaigns on the prestige of service to the nation in the army.

On February 21-28, 2015, when in the international media space, the notion that the events in Ukraine are an international conflict and not a “civil war” was still not widely understood, we organized an exhibition titled “Presence”. The exhibition showcased a wide variety of Russian weapons and military equipment that Ukrainian soldiers had seized during the conflict in eastern Ukraine. It was for the first time that the actual pieces of Russian military hardware, including tanks, multiple launch rocket systems, drones, sniper rifles, side arms, etc were demonstrated to the Ukrainian and international media as well as to the general public in the heart of downtown Kyiv, as clear evidence of the Russian Military Aggression against Ukraine. This was the first joint effort of the UCMC Strategic Communications team in the Security and Defense sector, the military, law enforcement, intelligence and other government agencies of high caliber. President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko opened the exhibition together with the President of the European Council and the leaders of Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and Georgia (check the gallery in the header).

All the above mentioned proactive measures and communications resulted in the reduction of negative coverage on the Ukrainian Army and its leadership in the media from 62% to 1% in five months.

But tactics are tactics and for the understanding of the systemic impact of Russia’s IO aimed at the Ukrainians and the Ukrainian army in particular, it is imperative to constantly conduct appropriate measurements and devise strategies based on a quickly changing situation.

One of the first and key elements for countering informational attacks and informational operations is to design and study an accurate map of actors, targets, channels, and resources. As part of such effort, our group initiated first in a kind survey of Defense Will within the Ukrainian army, civil population and civil population close to the war zone. Although the research was for internal usage, it became an effective tool for setting KPIs for many, previously vague, activities. After the survey was repeated in two years with the same methodology it became possible to measure dynamics of changes (see the chart below)

Estonia, for instance, has adopted the practice of making all their research results public to communicate (to Russia) that continuously over 80% of their population are ready to defend the country, should an act of aggression against them occur.

General measures to combat disinformation attack can be broken down into 5 steps:

- Become aware that you are under attack (until that moment the attack is the most effective).

- Identify channels, actors, and targets of the attack. Make a map.

- Design and proceed with fast counter-attack: communication and action (In some cases that would require from authorities to acknowledge the fault and take responsibility. Unlike wine bad news is not getting better with time).

- Think of your own positive narrative that would be proactive.

- Measure the result – adjust the message.

Based on our experience of countering ongoing Russian disinformation campaigns we can identify these recommendations as the most important

- Formulate/update the definition of disinformation (propaganda) and hostile language. Make it adequate to the challenge of the ever more creative Kremlin’s efforts.

- Change / adopt national legislation accordingly

- Do not let the Russian Media abroad enjoy preferences of free media, since they are not:

- Prove it legally

- Scrutinize budgeting sources

- Inform/educate the population about their manipulations

- Ban them

Special attention should be paid to the countries’ information space prior to the parliamentary or executive leadership elections since they are usually most vulnerable to information attacks during this time. Our colleagues from European Values Think Tank recommended to all EU states: “Given the evidence and urgent warning by many European intelligence agencies and security experts, European countries should develop their own national defense mechanisms & policies against hostile foreign influence and disinformation operations. Many countries are now facing prospects of Russian hostile interference in their elections and it is most probably not going to disappear during the upcoming years. Elections should be considered a part of the national critical infrastructure as they are a cornerstone of sovereignty.” And the infiltration of the country’s economy, energy, financial etc. sectors, transportation, security, information space needs to be analyzed holistically on a continuous basis.

Fakes, including from the states with vast resources, like Russia will remain and will not disappear from the modern media or political landscape. Therefore, it is pivotal for a state to obtain superiority in these fields:

1) Build resilience on a national level by strengthening of the national civic character as well as nurture critical thinking, tolerance, humanism and media literacy;

2) Build systems which enable faster responses to the attacks.

3) Be more creative with authentic responses and proactive strategic communications.

This is usually a challenge for any democratic state authority acting alone. But in cooperation with an enabled civil society and gradually more individual citizens actively engaged in defending the sovereignty and spreading knowledge and truth to others, it is doable. For all to win, however, an international collaboration of higher level is required, one that would ensure a continuous sharing of information as well as stepping up the regulation or self-regulation of the social networks, whose responsibility for spreading truth vs. contributing to truth decay globally should be leveled up.

Authors:

Nataliia Popovych, Co-Founder, Board Member, Ukraine Crisis Media Center

Oleksiy Makhuhin, Head of Hybrid Warfare Analytical Group of Ukraine Crisis Media Center