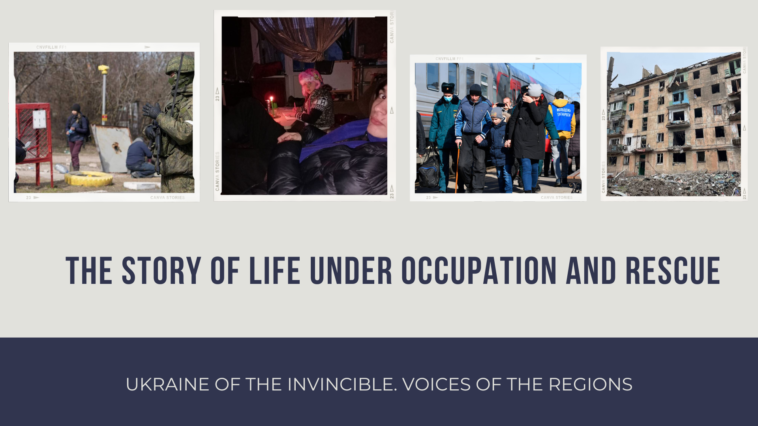

The forced displacement of Ukrainian people from temporarily occupied territories committed by the Russian invaders is genocide. This is the conclusion of the international legal report “An Independent Legal Analysis of the Russian Federation’s Breaches of the Genocide Convention in Ukraine and the Duty to Prevent”

According to Human Rights Watch, Ukrainian civilians detained by Russian troops not only lose their freedom, but also face threats to their health and lives because they are held without legal or public control. It demands that the Russian authorities immediately disclose the whereabouts and release all Ukrainian civilians who are in custody, detained in the previously or currently occupied territories.

Forced to bury neighbors and walk past corpses on the streets

Those who left Mariupol even remember the day – February 26. On that day the Russians felt that without blocking the road to Ukraine, they would lose all their hostages.

Viktoria Tereshchenko, 37, who now lives in Katowice, Poland, with her 16-year-old son Kyrylo and 7-year-old daughter Polina, shares harrowing details of life under occupation and rescue.

At first we didn’t leave because we believed it wouldn’t last long, – Viktoria recalls. – In 2014, we saw what hardship our acquaintances had to go through when they went to Western Ukraine, rented housing, spent all their savings and returned. Our whole life was in Mariupol, the apartment we bought 9 years ago and decorated with love. My husband is a sailor, at that time he was on a voyage. So we decided to stay in the city. We only moved in with our parents and took all the food we could from our fridges, pantries and a garage. This saved us from starvation, because we became hostages in our hometown.

Soon the family realized that they had made a mistake – they could not move even within the city. The shelling never stopped. Later, airstrikes were added to the shelling. The daily “norm” was 2-3 missiles that Russia fired at schools, hospitals, factories, theaters, and homes.

In early March, it got colder, – says Viktoria, – heating, electricity and communication were gone. We wore warm clothes and hats inside the apartment. We went to bed in the same way, only with our boots off. Many people moved into basements. We surrendered to fate and stayed in our apartment. Hunger did not threaten us. The frost made it possible to do without a fridge. The biggest problem was water. We drained the water from the heating batteries and drank it. It snowed on March 8. We were so happy and collected it from cars, railings, roofs – although mixed with soot from constant fires, it was our water supply.

The family cooked food in the yard. Not far from the house, a shell hit a bookstore, so there was a hole in the wall. Through it people were able to get books to make a fire.

We also collected wooden shelves in abandoned shops, – the woman recalls. – For some time, we went to the local pumping station to get water, but when we came across dead bodies there, we no longer risked leaving our yard.

In two months, the woman saw more deaths than in her entire life. She was happy the spring was so fierce – the frosts didn’t let corpses decompose and there was no smell of death in the air.

I don’t know what made me hold on and not go crazy, – says Viktoria. – Perhaps rare conversations with my husband. We learnt by word of mouth in which neighborhoods there was cell service, and my son and I went there to make a phone call while we could still charge our phone. The last trip took 2.5 hours instead of the usual 25 minutes. We passed by the drama theater, which was later bombed by the Russians. We walked along a street with corpses lying on it. They were just covered with something, as there was no time to bury them. I told this to my husband – I myself could not believe that I was living in that horror.

Then all the gadgets were discharged and they lost connection with the outside world. Viktoria says that many of her neighbors and friends could not stand it and just went out the fifth-floor window.

We saw horrible things: people torn apart by explosive waves, their remains collected in boxes to be buried in the yard, – she says. – We saw the death of a couple who went in search of water, and their three children were orphaned. Neighbors were buried. For weeks, we couldn’t get to the other end of the city, where our 84-year-old grandmother lives. Later we found out that she had fallen in her apartment and lay motionless on the floor for four days – without water or food. Luckily, she lived on the first floor. During the shelling, some people who were looking for shelter broke into her apartment. They saw our granny – put her on the bed, wiped her from defecation, gave her something to drink, brought something to eat. They looked after her all the time, until we finally got to her neighborhood. For our part, we also took care of our elderly neighbors, shared food with them.

In the early days, there were brave people who ventured out towards the unoccupied territories of Ukraine by cars. People envied them and resented that they stuffed their cars with things instead of taking a few fellow passengers. But after the convoys were shot, no one risked leaving.

People, driven to desperation, board Russian evacuation buses

After months in basements, cut off from the world, hungry and thirsty, people were glad for any help. Even if it was the face of a Russian soldier who peeked into the basement.

Later, my parents told me that the Russians had robbed our dacha, – says Viktoria. – They even took my father’s working rubber galoshes, and left their trampled shoes instead. They relieved themselves on beds and sofas, and wrote on the walls with their feces – “forgive us.” But the terrible humanitarian crisis made people rejoice when they were asked to leave for Russia. They just wanted to survive.

Nadezhda Kolobaeva, a Russian filmmaker from St. Petersburg, one of the few Russian women who help Ukrainian refugees to get out of Russia to the European Union, says:

All the refugees have the same narrative: they started bombing us, we moved to the basement, we had no water, no food, our house was completely bombed, after that we decided to flee, we saw evacuation buses – got in and left.

There was only one way: through filtration camps and interrogations to Russia. Only a few managed to avoid this route and get out through the previously occupied territories of Ukraine within the Donetsk region.

I was lucky to get out not through the camp, but through the village of Nikolske (old name Volodarske), – says Viktoria Tereshchenko. – I think that if I had got into a filtration camp, I would have failed to restrain myself. I was in a terrible psychological state and could have shouted anything in the face of soldiers. I would have called them fascists.

The woman was taken out by a volunteer who made his way to Mariupol with humanitarian aid from the Ukrainian side.

We left through the previously occupied territories of the Donetsk region, – Viktoria says, – a pregnant woman was in the car with me. Imagine, she’s in her 40s, in the last weeks of pregnancy – and 40 days in the basement with almost no water or food. We supported each other. She didn’t have warm clothes. I gave her my tights, helped her get dressed. The scariest moment was when we passed a checkpoint with Kadyrivtsi – soldiers of Chechen nationality. One took the birth certificates of all the children in the car and began to read the names in a terrible voice. The fellow traveler’s boy was frightened and did not respond. I thought that we would all be shot on the spot.

From there, the woman managed to leave for Zaporizhzhia, then for Vinnytsia, and from there for Poland. Here she visits a psychologist and dreams of forgetting the horrors she saw and experienced in Mariupol. She says that she still covers her head with her hands when she hears the sound of a plane or helicopter in the sky.

Money is a ticket to freedom

In order to get out of Russia, you need money, which refugees usually do not have, and psychological support of relatives who are in the unoccupied territory.

For four months, I persuaded my parents to move to neighboring Estonia, and from there to Poland, – says Ukrainian Tetiana Taranenko. – They were sure that the world had forgotten about Ukraine, that Ukraine had turned its back on its citizens, surrendered its territories to Russia. It is impossible to transfer money to Russia, because payment systems are blocked due to sanctions.

The woman says that she looked for an opportunity to evacuate her parents in secret chat bots in which Russians communicate. Someone feels guilty for the actions of their state and tries to help Ukrainian refugees break through to Europe, even buy them tickets. But most of them just profit from someone else’s grief.

We lived in Mariupol near Azovstal, – Viktoria Kuksiba shares her story, – it was shelled day and night. Many of our friends and neighbors died. They were buried in flowerbeds and parks. We managed to leave through the territory of Ukraine in the first days of the war. Our relatives – mother, brother, uncle – remained blocked in the city. I thought they had died. They thought that we had died. In Poland, I started looking for their names in various lists: dead, missing, evacuated. It turned out that they were “evacuated” to Russian Rostov-on-Don. I left my contacts through a Telegram bot. They spent three days looking for an opportunity to call me to Poland. They said that they were living as hostages, they could lose their Ukrainian documents, but they found a “volunteer” from Russia who undertook to deliver them to the Polish border for 60,000 rubles (almost $1,000). We collected money for a month, a month of tears, online communication, hopes. There was a huge queue at the Russian border, ten hours of waiting. And finally – a meeting.

It is very difficult to get our people out of Russia. Not only because of money, but also because of Russian propaganda. People who get into the Russian information field very quickly lose their critical thinking and common sense.

Viktoria Tereshchenko’s relative from Mariupol missed an evacuation train and left occupied Mariupol on foot. Her 1.5-year-old child fell ill. There was no other way to help her. Along the way, the woman threw away things she had taken with the intention of selling (laptops, expensive clothes, household appliances).

Several more of my friends were able to get out of the surrounded city on foot, – says Viktoria, – we managed to free my relative. We transferred the money and organized her departure through Latvia. A friend whose house was destroyed by a Russian shell, who took almost 60 buckets of earth out of the room to dig her wounded son out, now says from Russia: everything is ambiguous, Russia is not as guilty as it is accused of. She knows for sure that she lived in a peaceful city and that everything was fine with her before the Russian attack. Such strange metamorphoses happened to a person who shared a room with Russian television for several months.

If you are a man, why don’t you fight against “nationalists”?

Leaving Russia for Europe is half the trouble for a woman. It is much more difficult for men to do this. They are thoroughly checked – stripped down to their underwear, checked for patriotic tattoos and asked many questions.

Why aren’t you in the army? Why aren’t you fighting fascists, nationalists, and Banderovites? – they ask Ukrainian men at the border.

They are encouraged to fight against their country on the side of the Russian army. Orcs try to provoke our men so that they show their real attitude towards Russia.

Viktoria Dubovalova, who currently lives in Poland, says that she witnessed such interrogations. The woman was traveling from occupied Kherson through Crimea to Poland. The road to freedom cost her 1,500 hryvnias to Crimea and 500 dollars to the Polish border.

There were a lot of men on the bus, so it took almost a day to get through the filtration camp. The woman saw the humiliation that men had to go through. Although their only fault was that before the war they had worked as sailors, plumbers, and farmers. Hostilities took them by surprise in a peaceful city. They were forced to save their families from starvation, and then evacuate unarmed to safe European countries.

They were asked a lot of times if they were sure they wanted to leave Russia, because they would not be allowed back, because they were cowards and traitors, – says Viktoria Dubovalova. – But they were let out.

Russian mass media show that Russia not only bombs and destroys peaceful Ukrainian cities, but also allegedly saves people there. The Russian-appointed “mayor” of Mariupol, Kostiantyn Ivashchenko, says in an interview with the Russian propaganda media “Izvestia”: “whenever Russian military appear on the city streets, they give citizens their can of stew or a bottle of water.” However, the cynical PR actions of the Russian army do not mislead the majority of Ukrainians who have found themselves in the status of hostages. People continue looking for an opportunity to leave the territory of Russia, exchange contacts of carriers, look for volunteers and leave Russia.

Halyna Khalymonyk

8.07.2022

The material is prepared within the project “Countering Disinformation in Southern and Eastern Ukraine” funded by the European Union.