According to the Razumkov Center analysis, published on April 10, 2017, 69% of Ukrainian experts believe that the implementation of decommunization policy in Ukraine as a whole has a positive influence on the formation of national identity, 21% are convinced otherwise. The survey conducted by experts (a total of 105 questionnaires received) included scientists, professionals of public and private research institutions, politicians, experts, academics and journalists.

What are the grounds for a positive assessment of decommunization processes in Ukraine? UCMC tried to answer this question, based on the analytical report “European legal practices of decommunization: implications for Ukraine.”

Decommunization: definition by PACE, European Parliament and OSCE

Decommunization in Central and Eastern Europe started after the fall of communist regimes. In contrast to Nazism, there was no international trial of the crimes of communism, which would have condemned its criminal practices and identified common principles. As of today, some general decommunization principles have been defined by resolutions of PACE, OSCE and European Parliament. However, they are mostly of general scope and advisory in their nature.

Eastern European context of decommunization

Analyzing decommunization legislation of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as a the former Soviet Union, one can divide the countries into three groups.

The first group (the Czech Republic, Poland, the Baltic states) includes the countries where decommunization covered all or most areas of public life in one form or another. Decommunization resulted in condemnation of the communist regime with a possible ban on the use of communist symbols, lustration of the former officials, access to archives of communist repressive agencies and the provision of a certain status to individuals who had fought against the communist regime.

The second group includes the countries in which decommunization covered only certain areas of public life and was limited, for example, to lustration, opening access to the archives of the communist repressive agencies, ban on the use of communist symbols, etc. For example, Germany and Albania can be assigned to this group. In Germany, neither communism nor communist ideology were legislatively recognized criminal. Decommunization in Germany, in fact, was reduced to opening the archives of state security service of the former German Democratic Republic, lustration of its former employees and the ban on the use of symbols of one of the communist orientation parties.

Finally, in the countries that belong to the third group decommunization either have not taken place at all or was formal. This group includes such countries as Belarus and other former Soviet republics. Before the Decommunization Laws were adopted in 2015 Ukraine also belonged to this group.

Decommunization in Ukraine: legislation

On May 21, 2015, a package of the following “Decommunization Laws” came into force in Ukraine: “On perpetuation of victory over the Nazism in the World War II 1939-1945”, “On the legal status and honoring the memory of fighters for independence of Ukraine in the XX century”, “On access to archives of repressive agencies of the Communist totalitarian regime 1917-1991” and “On condemnation of Communist and National-Socialist (Nazi) totalitarian regimes in Ukraine and ban on propaganda of their symbols.” In a broader sense, the adoption of these laws means that Ukraine has made a decisive step aimed at breaking with the totalitarian past and its criminal practices of governance.

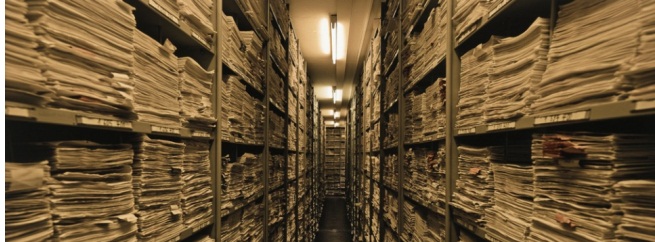

Opening KGB archives in Ukraine – the most open regulation in Europe.

While renaming streets and demolishing monuments of the Soviet era, as well as commemorating fighters for Ukraine’s independence in the twentieth century is sometimes criticized in the Ukrainian society and abroad, opening of KGB archives is definitely a revolution for adequate assessment of the past. Ukraine is one of the post-Soviet countries with the easiest access to KGB archives. This was experts’ conclusion based on the analytical report “European legislative practices on decommunization issues: implications for Ukraine.” Experts analyzed the practices of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, the Baltic countries, Albania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Georgia and Romania.

“Everything is open to everyone“

Ukrainian legislation practises the principle “everything is open to everyone”. That is, it does not matter whether you are a citizen of Ukraine or not, a relative or have some other relation to those who are mentioned in the documents. All have equal rights for access.

Increasing attendance of archives

In 2016, compared to 2014, the number of requests to visit the archive grew by 138%. The number of foreign researchers coming to work with the KGB archives increased twice in 2016 compared to 2015. More than half out of over 3,000 people who applied in 2016 asked for information about their relatives.

Conditions for access: general accessibility

To access KGB archives in Ukraine, there are minimum requirements: it is enough to provide all available information about a person you want to look up information about. You do not have to pay for the access, making copies using your own technical devices is also free. Foreigners are requested to send a copy of the first page of their passport. If a person sends this within a week, this will be enough to access the documents. Those papers that are still “top secret” in Russia (cases of victims of Soviet repressions), in Ukraine are generally available.”

“Right to know” vs. “right to privacy”

During the drafting of this bill, one of the main discussions was about the priority of rights. What is more important – the right to privacy, or the right of society to know what really happened under the communist totalitarian regime. Legislators came to the conclusion that, based on the risks associated with the hybrid war that Russia continues against Ukraine, it is important that everyone should have an opportunity to see what is actually stored in the archives, and everyone made their own conclusion. Therefore, one of the important points of the law is that the law on the protection of personal data does not apply to documents of repressive bodies. This makes it possible to say that Ukrainian legislations is one of the most liberal in Europe.

Terms for closing the information: 25 years of silence for the victims of repression

However, the law provides for the possibility for those who want to close information about them to do this, but not for more than 25 years. First of all, this applies to those who fell under repressions. Those who were perpetrators of repression, or were involved in them (for example, authors of denunciations) cannot do this at all, they cannot close anything concerning them.

“There was a case when a daughter of a former NKVDist wrote us a letter asking to close information about her. When we give her father’s case for examination, we will make copies from the pages where she is mentioned, anonymize them and give copies of pages with anonymous information about her,” says Andrii Kohut, director of the archive.

“There are no former KGBists“: opening archives and lustration

Lustration has been under way since 2014. It provides that everyone who worked for the KGB cannot work in state bodies of Ukraine. The archive makes a check, answers the lustration requests to the institutions. According to the Ukrainian lustration legislation, each institution carries out a check itself. In each department, there is a personnel department engaged in lustration inspection. They send a request for a person to the archive and ask us to give information whether they were employed. The archive searches and answers. If there is information that a person worked for the KGB, this is the basis for this person to be fired from or denied a job.

“There was a case when we received some letters from a man trying to prove that the KGB of the Udmurt ASSR had nothing to do with the KGB of the USSR, because the law says the KGB of the USSR, and Udmurtia was an autonomous republic,” the director of the archives said. “There were cases when people tried to prove that a person was just as an officer in some border guard unit, and during the Soviet Union border guards were part of the KGB. Sorry, the law is one for all. If you think that this does not apply to you, please go to court.”

The archive director described cases when people wrote requests to give information whether the archive has anything on them as KGB people, because they wanted to take part in the contest for a position.