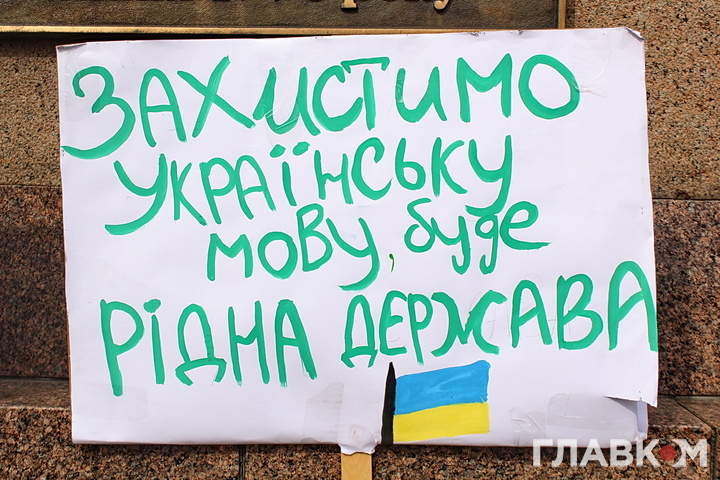

The text on the photo: “Let’s protect Ukrainian language to have our own state”

The language issue has never been easy in Ukraine, and it has become even sharper after the country gained independence. Ukraine is a multilingual state where Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian, Hungarian, Polish, Crimean Tatar, Bulgarian, Gagauz and other languages are spoken. In 2003, Ukraine ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and thus committed itself to protecting regional languages in the country. However, the most wide-spread languages are Ukrainian and Russian – the language of the former metropolis, currently a neighboring state that has been the aggressor towards Ukraine since 2014. The standoff between Ukrainian and Russian languages was frequently turned into a tool for the political fight inside the country and became subject to numerous manipulations. UCMC takes a look at what model of multilingualism is present in Ukraine, why the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages doesn’t work to protect Russian and what the new language law can change.

The multilingualism model. In the modern world in general and in the European Union in particular, there are quite a few states that have more than one official language. Also, there are states in which languages other than official ones enjoy a special status or are used respectively without any legal status. The list of such states includes Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland, Spain. The inclination for multilingualism grows inside any country as a result of migration and globalization. The language situation in Ukraine can be compared to that in some EU member states. At the same time, it would be wrong not to take into consideration how similar Ukraine’s situation is to the one post-colonial countries are facing. Historically speaking, for centuries Ukraine used to be part of the Russian Empire, then of the USSR, thus Russian was historically enjoying a higher, more favorable status in the society.

Language asymmetry.The historic absence of continuous statehood and the ties with Russia are still contributing to the so-called “language asymmetry”. After Ukraine gained independence in 1991, the majority of Ukrainians named Ukrainian as their native language (67,5 percent in 2001). However, it’s not only this choice that needs to be considered but the practical use of the language as well. When Ukraine gained independence, only 49,3 percent of the school children were studying in Ukrainian. Since then, the use of the native language at school has gradually increased, and in 2012 already 81,9 percent of the school children studied in Ukrainian. At the same time, even education does not ensure positive dynamics in the practical use of the language. Today, 68 percent of Ukrainians consider Ukrainian their native language, over 80 percent study in Ukrainian, but only 50 percent do speak it at home. Even less, 39 percent, use it at work. Thus, the language Ukrainians consider their native and are being educated in is not the one they use in their professional life.

The most widespread native languages according to the 2001 census.

Direct speech:

“The number of native speakers of Russian in Ukraine currently does not exceed the number of Ukrainian native speakers but they still have more power,” political analyst and language expert Volodymyr Kulyk.

Rigid and penetrable language borders. Ukraine’s situation is a particular one also because it is impossible to clearly outline the territory of the Russian-speaking “language minority”. Russian is neither the language of a certain region nor of an area of compact settlement of the minority but the language of the former metropolis that too many Ukrainians still has a higher status then Ukrainian. To compare, the situation in Ukraine is contrary to the Swiss model when the state is made up of cantons in which the languages are different and they are almost not mixed as such. In the Swiss model, the adaptation rule applies: one should switch to the language spoken in the region upon crossing the language border. The situation in Ukraine is different. A very small number of people consider their language being “just Ukrainian or just Russian”: the majority are fluent or have a strong command of both languages. The question is, how the spheres of the use and competence for the languages should be distinguished, in the situation when the majority of citizens are fluent or have sufficient command of both languages.

Ukraine and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) adopted in Strasbourg in 1992 under the auspices of the Council of Europe aims to “protect and promote historical regional and minority languages in Europe”. Ukraine ratified the Charter in 2003. According to the law passed to ratify the Charter in Ukraine, the provisions of this law are applied to the languages of the following national minorities: Belarus, Bulgarian, Gagauz, Greek, Jewish, Crimean Tatar, Moldovan, German, Polish, Russian, Romanian, Slovak and Hungarian.

Philosophy of the Charter: The Red List of languages. The Charter is intended to protect not as much the citizen’s right to speak a certain language but the languages themselves preventing them from disappearing the same way the Red List does for the threated plant and animal species.

Ukraine: protection of the stronger, not of the weaker. Many experts are of the opinion that a political mistake for Ukraine was not the signing itself and the ratification of the Charter but the fact of including Russian language in the list of minority and regional languages. The Charter is directed towards minority languages – the ones used by minorities, or the ones under the threat of disappearance or decline. It is not true in the case of Russian language in Ukraine. Ratification of the Charter became an additional tool for the political forces that were trying to apply protecting mechanisms of the Charter to the language that was dominating anyway. It leads to the discrimination of the language that is formally the language of the majority while in fact finds itself in the minority.

Direct speech:

“In Ukraine, three languages would need to be protected following the recommendations of the European Charter. They are Crimean Tatar, Karaim (its native speakers live in Crimea) and Gagauz (its speakers are found in Odesa region)”, language expert, professor Oleksandr Ponomariv.

What can the new language law change?

What is stipulated in the law. The draft law no.5670 “On the State Language” that is supposed to substitute the so-called “Kivalov-Kolesnichenko language law” that was recognized unconstitutional, only regulates the use of the official state (Ukrainian) language and does not apply to the languages of national minorities. [Read also: “The Truth Behind Ukraine’s Language Policy”] The law does not apply to private communication and religious rites, thus the law will not introduce any additional restrictions for an average citizen. At the same time, the law binds civil servants, teachers and medical workers to have an excellent command of the official language as well as regulates the use of the official language by the state agencies and in the public domain (including in advertising, media, science, cultural events, product information, services, healthcare and transportation etc.)

The law vs reality. Quite often misunderstanding starts when observers from outside of Ukraine do not understand what is obvious for Ukrainians: implementation is not a must for a law. In a rule-of-law state, it is enough to have something stipulated by law to have it implemented. It is not always like that in Ukraine. Despite Ukrainian has been enjoying the status of the official state language for over 25 years now, there is quite a number of Ukrainian politicians who willfully do not speak Ukrainian.

Direct speech:

“Realities of Ukrainian bureaucracy require that it is put down in the form of an instruction for civil servants. They will more likely follow the instructions that regulate their activities than the direct provisions of the law. Moreover, political will is required. A law is implemented only when someone insists that it needs to be implemented.

For example, the so-called “Kivalov-Kolesnichenko language law” foresaw the status of the official state language for Ukrainian in the entire territory as well as the status of a regional language for Russian and some other languages in particular regions. The regional status of Russian was adopted for all eastern and southern regions. But the “Kivalov-Kolesnichenko law” was not duly implemented. The overall majority of the document flow was in Ukrainian only, whereas it would have needed to be written in both languages. The oral communication there was made Russian, while the correct way would have been to let the citizens choose. Neither the rights of Ukrainian nor Russian speakers were secured. In practice, it happens the way in which it is the most convenient for the civil servants,” Volodymyr Kulyk, political analyst.

The new law and control over its implementation. It is exactly the reason why the new law foresees a monitoring and inspecting mechanism to implement it. The law introduces the position of the Envoy for protection of the state language as well as the service of language inspectors. They will be exercising language monitoring and inspections in public sector as well as in other spheres where the use of Ukrainian is mandatory. It goes unsaid that they will not interfere with private communication. When the law will be adopted and how it will work, the time will show.