The resurgence of invasive psychiatric treatment in Russia? Or a method of torture that never dissappeared?

Since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia on February 24, 2022, there has been a surge in reports of invasive psychiatric treatment within Russia. This phenomenon signifies a strategic approach to suppress opposition and exert dominance over individuals.

This article aims to examine the widespread implementation of these methods, drawing on the research conducted by Russian video blogger and journalist Karèn Shainyan, who shed light on their historical roots in the Soviet era and their resurgence during the Russian-Ukraine War. In addition, insights from experts, journalists, and individuals some of whom have experienced these forms of torture provide valuable perspectives on the implications of a country which claims to support the UN charter of human rights.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, the Russian government has been found using invasive psychiatric treatment in a number of cases across Russia on individuals suspected to have behavioral abnormalities. These individuals, as shown by Shainyan, have been subjected to this heinous torture methods for actions against the state, such as pouring paint over a banner which supports Russia’s genocidal policy against Ukraine, refusing Russian citizenship, and engaging in acts deemed to undermine the state and its objectives.

These cases include a Ukrainian citizen from Kharkiv, which was then temporarily occupied by Russian territory in 2022; was forced to evacuate through Russian territory. Upon her evacuation she refused to comply with the enemy authorities, and refused to accept the forced Russian citizenship, leading to her arrest and being subjected to invasive psychological methods in a psychiatric hospital. Another activist Dmytro Lamany, who set fire to a military enlistment office due to forced mobilization, is reported to have been subjected to the same treatment.

There were also numerous individuals who were also subjected to the aforementioned invasive treatment for allegedly spreading false information or publicly displaying Ukrainian symbols in public or via internet streams. Shainyan recounts the most famous case of all, involving Aleksandr Gabyshev, a shaman from Yakutsk, Siberia, who has been confined to a psychiatric hospital in Novosibirsk for four years due to his organized protest. This protest was to walk from Yakutsk to the Kremlin, (over 5000 miles) with the intention of exiling Putin from the Kremlin.

Institutionalized Torture: The Grim Reality of Invasive Psychiatric Treatment in Contemporary Russia

In Russia, invasive psychiatric treatment has a dark history dating back to the Soviet Union. These methods were not intended for genuine treatment at the time, but rather as a form of torture.

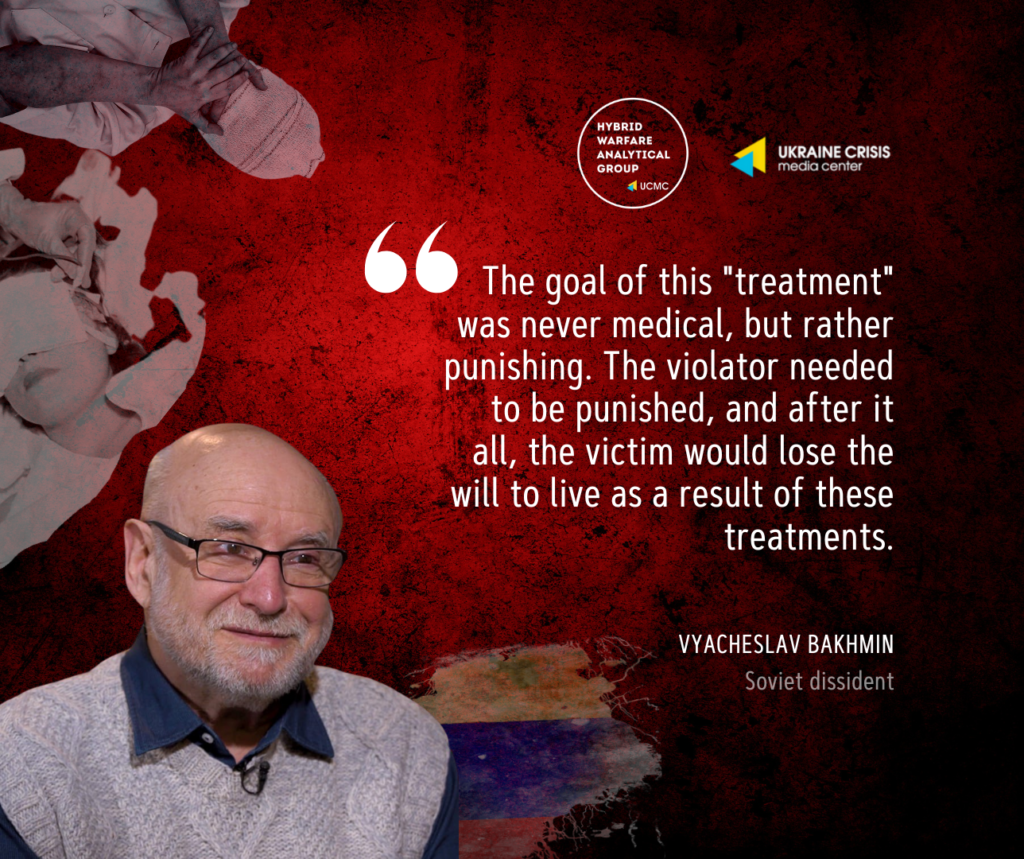

For their opposition to the state, dissidents such as Vyacheslav Bakhmin and Viktor Davydov faced imprisonment and psychiatric confinement. The Soviet regime regarded those who rejected the societal state as mentally unstable, because, as Bakhmin points out, even the thought that the state was less than perfect was considered a sign of mental illness. As a result, in order to maintain power, the authorities used psychiatric hospitals to silence any forms of dissent.

In Russia, invasive psychiatric treatment is designed to inflict pain and discomfort, inhibiting thought and reducing individuals to a submissive state. As repression in Russia grows, so do the use of these methods. Vyacheslav Bakhmin, a dissident and the former member of the Moscow Helsinki Group’s oldest human rights organization – founded in 1976 to monitor Soviet compliance with the Helsinki Accords and to report to the West on Soviet human rights violations. The organization was, however, dissolved on January 25, 2023, and employees of the company were imprisoned for spreading lies and fabricating evidence to discredit the state.

He describes the use of large doses of tranquilizers as well as torture techniques such as wrapping a wet blanket around the bare skin of the violator, which in the process of air drying would then shrink and squeeze the wrapt surface of the body, causing excruciating pain.

“The goal of this “treatment” was never medical, but rather punishing. The violator needed to be punished, and after it all, the victim would lose the will to live as a result of these treatments,” Vyacheslav Bakhmin

From Human Rights Activist to Zombie

Viktor Davydov, a journalist and Soviet dissident, described how staff in the psychiatric prisons restrain individuals and openly express their intention to reduce the prisoner to helplessness. “Prisoners may be physically bound for an extended period of time,” he told, “accompanied by agonizing screams.”

They added how, often, prisoners exhibit a zombie-like demeanor after being released from this treatment, with drooling saliva, which therefore teaches the prisoner to submit, using the fear of the pain to force their subservience. But the torture is not limited to medical, they are frequently isolated, humiliated, and subjected to sexual violence.

It is clear that this treatment is based on control and punishment rather than genuine medical care, and Bakhmin explains how it would be a mistake to say that these treatments are seeing a revival; they were still used over the last 30 years, but the Russian-Ukrainian war has highlighted these cases. Bakhmin claims he has never heard of political prisoners being tortured in an actual prison. The difference, he claims, is that political prisoners are subjected to morally humiliating treatment, whereas political dissenters are subjected to physical treatment such as torture.

According to Davydov’s personal experience, standard hospital treatments pale in comparison to the harsh methods used in Russian prisons. These treatments have serious psychological consequences, such as loss of body control and a distressing inability to remain still – which he referenced as to one of the most gruesome parts of the treatment. “Inner anxiety necessitates constant movement.” According to Davydov, psychiatric hospitals in Russia where these treatments are administered resemble the oppressive environment of gulags. “Patients are constantly monitored, and the use of neuroleptics exacerbates their suffering.”

“They won’t let me out until this war end”

Alexsi Onoshkin, a blogger from Nizhny Novgorod, was sent to receive invasive treatment in April 2022 after complaints about his ‘deviations’. He is currently in a psychiatric hospital, where he is allowed one hour of phone time per day for communication. He told the interviewer that the only previous diagnosis of mental ‘deviations’ he had been as a child, when he was misbehaving at school.

While speaking on the phone with the journalist, he displayed signs of severe isolation, fear, and exhaustion, describing how his usual sociable self is no longer who he is. He has become isolated and has no way of knowing how the treatment is affecting his mental condition because isolation is a major factor in his depression.

A Technique Deeply Rooted into the Institution

Vera Shengelia, Trustee of the Vital Way Foundation, describes how efforts to reform the system are hampered by the regime’s authoritarian nature and a lack of democratic processes.

“It was not and still is not possible to reform these ways during the Putin years because reform necessitates a number of democratic processes, such as elections and government officials’ accountability for the normalization of violence. But it wasn’t possible because if you started talking about reform and freedom on such a large scale, the authoritarian regime’s system would explode with such ferocity that you’d never be able to do it.”

Addressing these widespread human rights violations necessitates significant structural changes, as well as the establishment of an independent court system capable of ensuring justice and protecting individual rights. The use of invasive psychiatric treatment as a tool of repression and control underscores Russia’s desperate need for change. These methods are used to manipulate and coerce people into complying with authorities, infringing on their basic rights and freedoms.