The Russians killed hundreds and injured thousands of Ukrainian kids. Tens of thousands were kidnapped and forcibly taken to Russia. Many more were orphaned, had to flee to another city or country, and lost not only the opportunity to study, but also ordinary peace. You can understand the scale of this catastrophe only by looking closely at individual fates.

When I ask her to tell me what her life was like before the war, Yulia says: it’s hard to recall, the war seems to have erased and distanced everything. Of course, she will recall and tell me. However, her memories of the war are more vivid.

I’m also looking at this panorama through the eyes of a teenager, now 19-year-old Yulia Lahuta. Of course, I read and constantly heard about their Velyka Pysarivka, the outskirts of the Sumy region and the country, bordering Russia’s Belgorod region. In the first weeks of the war, we kept calling our colleagues from the occupied or actively shelled towns with a not-yet-traditional “how are you?” But adults’ attitudes and our gradual habituation to the war aren’t as frustrating as those of children and teenagers, when a girl says: “At some point, I looked and understood – where’s my childhood, I no longer have it…” And she talks about home: “…I’m drawn to Pysarivka. It’s mine… We come home from time to time to see how it is. There are very few people there. I take a stroll, walk the streets, listen to music. And for some reason I’m not afraid. I know what to do if shelling suddenly starts: when it hits far away, when it hits close…”

What to do if war breaks out?

It was scary in February 2022. Their Velyka Pysarivka, which is less than 10 kilometers from the Russian border, was among the first in the country to see convoys of vehicles moving in from abroad. Yulia woke up early and heard her father telling her grandmother that the war had begun. And then panic struck – without hysteria, it just filled everything inside, because something’s happening, and you don’t know what to do, what’ll happen next. No one had the necessary experience, let alone a girl who has not turned 17 yet…

Her father knew what to do. He began to pull mattresses, blankets, pillows down to the basement – it was already clear that they would have to use the basement. They put documents in one bag and medicines in another. And then they carried the bags with them all the time, one for dad and another for mom, to and from the basement.

In those first hours, questions appeared in the school chat room: should we go to school or not? Now it even seems ridiculous: what lessons when enemy vehicles are moving down the neighboring street? But at that time, there was uncertainty, confusion, and a desire to at least somehow understand what to expect. The students were told to stay at home and hope for the best.

Then people began to write: tanks and cars are passing through our street. Then the news came that Okhtyrka – their district center – gave a fight. Then, that planes were flying, that Okhtyrka was heavily bombed… The only good thing in those days was that the Russian convoys that were transiting through the town were returning. While 30-40 cars went there, only three or four cars returned, and at high speed. It was comforting and hopeful.

Meanwhile, shops and pharmacies in Velyka Pisarivka were emptied, as residents stocked up. There were few people on the streets. However, there were people who cared, dared to go to nearby villages, where they could buy something, and brought it. It was a time of restrictions – a kilo of cereal per family, a loaf of bread. So that there was enough for everyone…

Her father and other men discussed what to do if their homes were attacked, how to defend themselves. “Someone made Molotov cocktails, and it’s good we didn’t use them,” says Yulia, because in the rear of the Russian troops, where they were, it would have been more like a suicide. Her father got some fuel for the car in case they had to leave. But there was no chance to leave – the enemy was driving on the roads.

No, no one in their village seemed to be personally affected. The Russians rushed to Kyiv, stumbled over Okhtyrka, but had not yet committed the horrors that would later shock the world. Of course, there was constant shelling. And soon the basement made everyone feel sick, just sick, and people began to fall ill because of the humidity. Grandma Nina was the first to protest and didn’t go to the basement during the next shelling. The others went down, and then suddenly there was an explosion, very close. They got scared and ran upstairs. “I screamed at my grandmother for not going down to the basement,” recalls Yulia. “It wasn’t me screaming, it was my fear…”

And one day, after some distant explosions, there was a bang so close that it hurt the ears. Oleksandr, her father, looked outside, and then looked back at them: the neighbor’s fence was gone. And then he saw their fence was gone too, as well as the windows, the slate on the roof was damaged. He returned to the basement and said flatly: pack your things and leave tomorrow.

It was March 24 – a month after the occupation began, right before Yulia’s birthday. She was born on April 1 – exactly on April Fools’ Day.

“Although mom was already in hospital and dad knew I was about to be born, he couldn’t believe it when he got a call on April 1 and was told he had a daughter. He thought he was being pranked,” the girl says.

Until 2022, she always celebrated her birthday at home, with her family. Her godparents and closest friends came, but always at home. That pre-war life, which still breaks through in her memories, is very homely. Together they would have breakfasts and dinners, play board games, especially Monopoly.

“I used to tell my parents everything, well, just everything: what I did well, what I did wrong. My brother told me everything too. Since he’s younger, I could tell him that something he did wasn’t okay. Well, I could tell on him to our parents, and we would fight. Now we are true friends…” says Yulia.

If you love home, a foreign country won’t warm you…

… Each destiny is unique, although somewhat similar to others. Each misfortune is personal, but when it is big and shared, then one story reflects thousands or millions of similar ones… A relative took Yulia, her mother and her brother Stanislav to Poltava. From there, they took an evacuation train to Lviv. A long line at the pedestrian crossing to Poland. Finally, Riga, Latvia. Mom bought a cake for her birthday, but Yulia didn’t want it, she couldn’t… It turned out that it’s not the cake that matters, but where and with whom you can share it…

The aid provided in Latvia was important, but not enough to live on. Mom got a job. Yulia, already 17, was offered a job as a waitress. She was afraid because she didn’t know the language, but over time she learned the necessary phrases.

Later, she went to Latvia for a few more months. They decided that the war might drag on, the situation would be uncertain, so it would be good to get a residence permit to facilitate a probable evacuation. She worked as a waitress again, 26 days a month, sometimes for 12-15 hours. Because she is stubborn and, it seems, wanted to prove something – either to herself, to someone, or to her fate. But that’s when she realized: her childhood was gone…

Dad and grandma stayed at home. They patched up the roof, boarded up the windows, fixed the fence, lived… For six months, Yulia begged to go home, and finally her father allowed her to. After the region was liberated from the invaders, it was regularly fired on, but mostly villages that were very close to the territory of Russia, less often – Velyka Pysarivka. So Yulia’s mother stayed to work in Latvia, and Yulia and her brother went to Ukraine.

There are no classmates left in the town. When any of their friends came back from time to time, they met up and went for a walk. There was a lot of destruction, many people died.

And what were people’s attitudes? People are different. Some try to do what they can. Some bring food. For example, Yulia’s father and other men put sandbags in the windows of the surgery: the hospital was under fire, but they had to treat and operate. Some people leave, while others refuse categorically. Someone just waited…

But you have to live

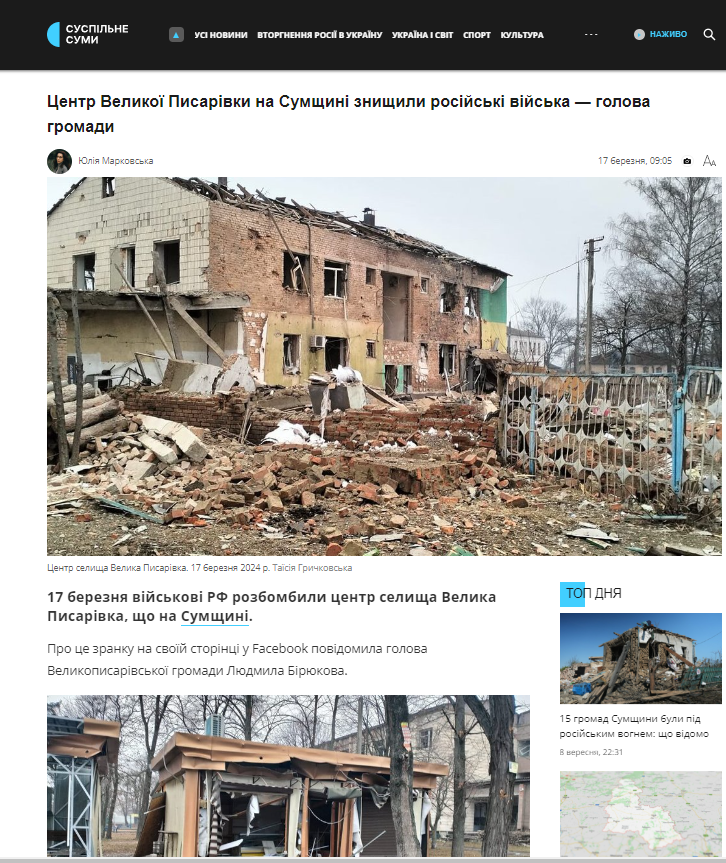

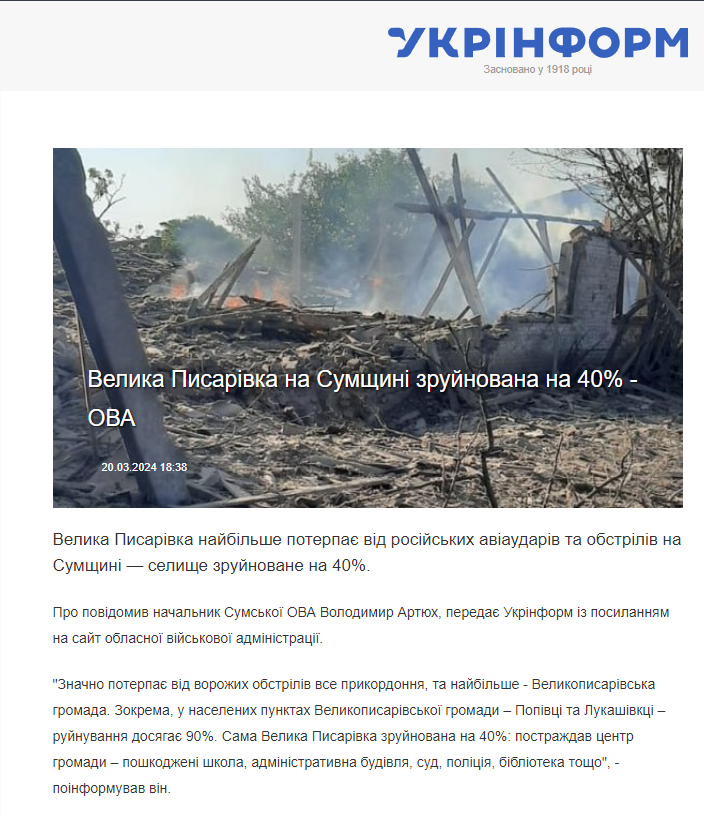

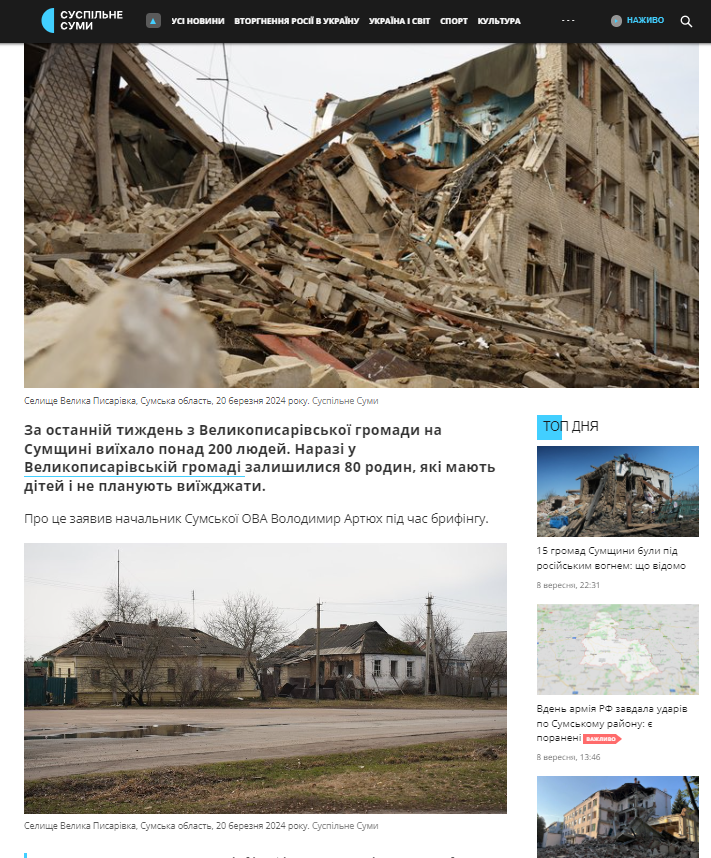

In March 2024, the Russians began to destroy the Sumy region, first of all, the Velyka Pysarivka community. The shelling was simply devastating. Smart bombs flew in every day, and explosions never seemed to stop. Yulia’s school was hit by what is said to be the heaviest bomb of the war and was almost destroyed. The town center was methodically destroyed. People from the villages and Pysarivka were evacuated by buses and cars, and where shelling and bombing had already destroyed roads and bridges, people were taken out on foot – it was dangerous to stay in the villages that were being shelled.

“I’m used to explosions. We lived with them for six months after we returned from Latvia. When there is an explosion, we know what everyone has to do. But then it became depressing. I’m sitting here, I have to do my homework, but I’m just sitting “between two walls”. And what do those walls matter, even if there are two, if smart bombs are flying…” recalls Yulia.

They moved to Okhtyrka. They live near the forest, so during air raids Yulia often goes there – it’s more comfortable among the trees than in the basement…

They share an apartment with another family. It’s expensive to rent a separate apartment, and it’s almost impossible to squeeze in behind those who want to.

Dad works as a leading specialist in the plant protection, phytosanitary diagnostics and forecasting office of the phytosanitary safety department. Stas is at school, yes, the one that no longer has premises, but has teachers and works online. Julia is also an online student at Sumy State University. She entered during the war, in 2022. She decided to be a journalist. The idea came to her after a training session. When she was in the ninth grade, her class teacher Kateryna Obidets made her participate in it. There was Covid, quarantine – who needs training? However, she liked working in a team, and was also impressed by online communication with professional journalists who spoke so interestingly about their work. She makes her dream come true.

“And this year, I told my dad that I didn’t want to work in the summer. He agreed that I needed to rest. No, he never pushed me to work. But I wanted to agree it with him. And finally, I decided that I should work on myself,” says the student.

What does it mean work on yourself? Yulia wants to get her driver’s license – she has already passed the theory, and practice is still ahead. She organized the first family vacation in years. She bought tickets to Odesa and made her father face the fact. So the three of them, her dad and brother and she, had a little vacation at the sea.

She also had her first non-online practice: she went to Sumy to talk to the website’s editorial staff and make live materials. “… I also work in the project “News camp Ukraine-Germany”. The first training was in the Carpathians, the second in Leipzig. I learned a lot. And most importantly, I communicated live and I’m happy to have made new friends,” Yulia says.

We are talking in the training room of the project that Yulia liked.

“And who’s the boss in your house – you or granny?”

“My dad,” she smiles, “but we usually agree. When it comes to cooking, it’s the one who has time, me or my granny. If we have to do something hard, it’s my dad or my brother.”

…She will go home to Velyka Pysarivka again next weekend, although special access to the 20-kilometer border zone has been introduced. She has to clean up, help in the garden, because they planted everything in the spring.

This is the life of a girl who was forced to grow up. Because of the war.

Numbers and people

Perhaps it’s natural that people get used to everything – it’s a way of self-defense, otherwise they might go crazy. But it’s scary when death, destruction, and separation become commonplace.

In the first weeks of the war – I know it from my own experience and from other people’s stories – there was some inner burning shame when, say, I made myself a cup of coffee, because somewhere in Mariupol people didn’t have water at that time. After one of the latest shelling of Sumy, when a missile destroyed almost forty cars in a parking lot, smashed windows and mutilated the balconies of nearby high-rise buildings, an elderly couple of passers-by summed up: well, it’s okay, they didn’t hit the house.

We are changing. And we stop feeling. And when we read another report that with the intensification of the bombing in the Sumy region, more than 20,000 people were evacuated from border settlements in August (only in August!), we sometimes block ourselves from understanding that behind each unit of those thousands, out of those millions of displaced, destitute, and dead people, there is a particular person. For example, a girl from a small town…

Author: Alla Fedoryna.

Photo from the heroine’s archive

Supported by the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine. The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Government.