During the Soviet era, disability sounded like a sentence. People were cut off from society, confined to special boarding schools and enterprises. Disability was supposed never to exist in the Soviet world, because it spoiled the ideal picture of the state’s “success and power”. Echoes of such narratives can still be heard today. Not all Ukrainian cities have facilities with ramps, audible traffic signals and public transport, not to mention smooth sidewalks. People with disabilities often feel frustrated, the voice of the Soviet past seems to whisper to them: “You’ll never have a happy life.” But in Ukraine there’s a caring civil society that believes in changes and makes them happen. The war adds to the urgency of the matter, as the number of people with disabilities increases every day.

Anatoliy and Daria Sass are the founders of the NGO Initiatives of Slobozhanshchyna, and have been working on inclusiveness for a long time. Since 2015, they’ve been transforming post-Soviet Sumy into a modern and accessible city and helping the blind to believe in their future. The couple meets people who are absolutely unsure of their abilities, and eventually a smile appears on a face that has been deprived of it for a long time. Indeed, disability is not a sentence.

“Once a woman from the Krasnopillia district visited our NGO,” Anatoliy begins. “She had completely lost her eyesight as a result of diabetes, when she was 37. We helped her learn how to use TalkBack, an accessibility feature that lets blind and visually impaired people to interact with their Android devices using taps and voice prompts.

When TalkBack is enabled, objects on the screen are highlighted with a focus frame, and the device uses audio prompts to tell you what’s on the screen. Today, the woman teaches visually impaired people at the Podillia Comprehensive Rehabilitation Center to use smartphones and computers and inspires others to keep going.”

Anatoliy and Daria have been visually impaired since childhood. When they got married, they ran a joint business, recording audiobooks first for themselves, and later for the people of Kramatorsk, where they lived before Russia invaded Ukrainian territories. The family led a fairly active lifestyle. Daria worked as a tutor, teaching Ukrainian language and literature. Anatoliy worked as a security chief at the local enterprise of UTOS (Ukrainian Society of the Blind – Ed.). The Sasses helped transform Kramatorsk into a barrier-free city. Before it was seized by the occupiers in 2014, Kramatorsk was developing: accessibility committees were meeting, traffic lights were equipped with audible signals, and public transport stops were announced. In April 2014, Russian militants invaded Kramatorsk and shots were heard in the city. The occupiers seized administrative buildings one by one. The Ukrainian troops tried to liberate the city from the terrorists (now the city is controlled by the Ukrainian government, but it is under constant shelling – Ed.). Those events made the couple leave their home and their peaceful, pre-war life.

“When the anti-terrorist operation began, staying in Kramatorsk was dangerous, especially for us, the blind. So we decided to move to Terny, the Sumy region and live with Anatoliy’s mother,” says Daria.

New opportunities for Sumy

The Sasses lived in Terny for a year, but then realized that they wanted to live in town and moved to Sumy. They rented an apartment and began to settle in. But very soon the couple found out that the regional center was not about barrier-free environment. However, this situation did not make the couple give up; on the contrary, Anatoliy and Daria realized that they had to act.

“The situation with accessibility in Sumy was very embarrassing, and we decided to do something about it. We met a couple of young people who also wanted changes, and we created the NGO Initiatives of Slobozhanshchyna in August 2015. Later on, audible traffic signals appeared in our city, although there are four of them so far,” says Anatoliy.

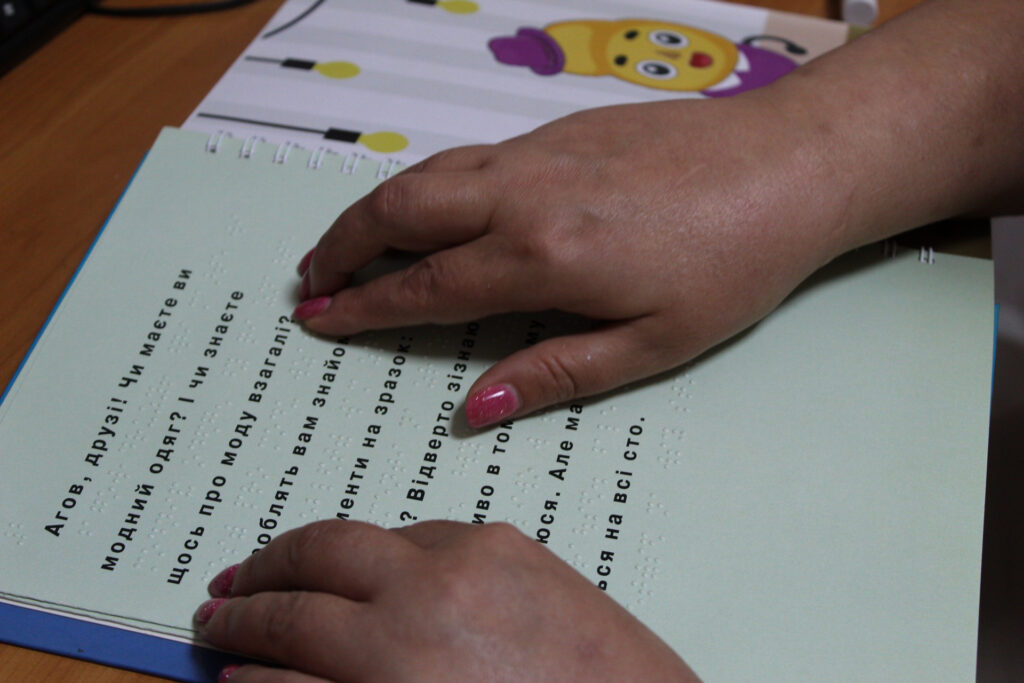

Of course, the Sass family’s activities did not end with the installation of audible traffic signals in Sumy. They initiated introducing external and internal audible announcements in public transport, because it is very hard for visually impaired people to find their way around, and they have to ask a driver or passengers to tell them the bus number and then warn them about the stop. Soon they were consulted on how to equip inclusive facilities, and the couple themselves actively helped people with visual impairments. They were approached by those who had been blind since childhood or as a result of illness, accident, injury, etc. Daria and Anatoliy helped them adapt to perceive the world by touch and hearing: they shared audiobooks, taught Braille, helped them learn to use computers and smartphones, organized joint visits to cultural events, gave advice on how to better navigate the outdoors, and helped find a job. So, the person who turned to them had a chance for a life filled with opportunities for development and self-realization.

The couple seemed to have recovered after the war had made them start their lives from scratch. But they would soon hear the sounds of enemy gunfire again.

How people with disabilities fled from shelling

The Sasses met the outbreak of the big war in Sumy. The first thing they felt was despair and confusion. Daria did not leave the house because she felt in danger. In the first days, enemy vehicles drove through the streets of Sumy, and there were fierce street battles on the outskirts of the city. Anatoliy moved around the city and helped people in need. After two weeks of encirclement and Russian shelling, the Sumy authorities announced “green corridors”. It was the first opportunity for the people of Sumy and the region to leave the war zone. On the first day, no special buses were provided for people with disabilities. And the announcement of opening the “corridors” was made an hour before, which meant that there was hardly any time to gather people and find transportation.

“We had lists of people with disabilities who want to leave the city. We had compiled them in advance in case of evacuation. On the first day, we didn’t have time to get ready, and the officials’ advice to look for our own transportation, to be honest, made me angry. Of course, I was upset, because many of my friends who are not visually impaired were able to leave that day. But what could we do? I began to address officials with this issue. I wrote to the head of the military administration, at that time Dmytro Zhyvytskyi, and I also turned to Iryna Vereshchuk, the Minister of Reintegration of the Temporarily Occupied Territories. I wrote that we were left to our own devices. The next day, the authorities did provide a special bus, and we gathered our people. Among them were people with visual and musculoskeletal disorders. Not everyone dared to go,” says Daria.

But that was not the end of the couple’s disappointment. When the bus arrived in Poltava, Anatoliy and Daria realized that the authorities hadn’t organized further evacuation of people with disabilities from Sumy. On arriving at the station, 20 people with disabilities found themselves out in the open at night. It was two in the morning, no one was there to meet them, and they had to spend the night in the waiting room, waiting for an evacuation train to Lviv.

“Just imagine, people in wheelchairs had to stay all night at the train station and then wait half a day for a train to Lviv, which departed at 3:00 p.m. It was terrible. But then we faced more trials. When the evacuation train arrived, we couldn’t get on it, because we weren’t given a separate train car. We didn’t need a whole car, but we needed a safe access to it. We couldn’t get through the crowd, because there were many people who wanted to leave. Then I called the government commissioner for the rights of people with disabilities and, ultimately, we were given a separate car,” says Anatoliy.

The Sasses stayed in Mykolayiv, a town in the Lviv region. They continued to help visually impaired evacuate from dangerous areas. Many people left for Poland then. The Sasses did not forget those who remained in Sumy either.

“Since there was a problem with medicines in besieged Sumy, every morning I would go on a tour of pharmacies and look for necessary medicines, and then send them to the city via my friends,” recalls Anatoliy.

“This is probably our calling — to help people”

In April 2022, the Sumy region was liberated from the Russian occupiers. Later, the couple returned to Sumy and significantly expanded their activities. They began helping not only people with visual impairments, but also other nosologies.

“Thanks to grants and partners, we provide humanitarian aid, assistive technologies and financially support those in need. We try not to leave any appeal unattended. Even if we can’t provide the necessary support ourselves, we tell a people where to go and send them to other organizations. We try to help everyone whenever possible. Because when a person is in trouble, you can’t ignore it. This is probably our calling — to help people. Now, we are also working on the adaptation of soldiers and civilians who lost their vision as a result of the war. We provide legal and psychological assistance to residents of the Sumy region and internally displaced persons,” says Daria.

In her opinion, the number of visually impaired people will only increase with the war. Therefore, the government should think of barrier-free possibilities and inclusiveness in every Ukrainian city. Barrier-free environment will make a blind person feel more confident and secure. The matter is that, along with the constant threat to life caused by Russian aggression, visually impaired people experience additional stress every day as they lack accessibility in town. They can hardly get to a shelter on their own: even a bumpy sidewalk or an improperly parked car can be a huge obstacle. The Sumy shelters are not equipped with tactile strips that could help to better understand the right direction, so visually impaired people can only rely on those who care to provide guidance.

Not to pass and offer help is everyone’s personal decision. People with disabilities are not used to demanding anything from society or hoping for someone’s empathy. But probably everyone dreams of arranging inclusive cities. Then they won’t have to ask anyone to help them cross the street, each time fearing rejection. The Sasses believe that caring will be not only their credo, but also the government’s concern.

Installing audible traffic signals, tactile strips, Braille is more important than ever — every citizen of Ukraine should have the right to safety. Daria and Anatoliy urge the government to consult people with disabilities when implementing ideas for making the country barrier-free. Without their involvement in the process, an accessible environment cannot be created.

“The principle of nothing for us without us should work here,” says Daria. “You don’t have to do anything ‘for show’. You should definitely consult with those for whom these actions are taken. And our opinion is important.”

Author: Anna Tolstosheyeva

Supported by the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine. The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Government.