Propaganda has been a powerful tool for governments and organizations to shape public opinion and promote their agendas. One common strategy used in propaganda is portraying children as symbols of innocence, purity, and hope. This strategy aims to evoke emotional responses from the audience and create a sense of trust and legitimacy for the propagandist message.

With a long history of state-controlled media and government propaganda, Russia has been known to use this strategy frequently.

This research aims to analyze children’s use as symbols in Russian propaganda through content analysis, a method that allows for a systematic and objective examination of media content.

By analyzing a sample of Russian propaganda materials, including news articles, social media posts, and videos, this research aims to answer the following questions:

• What types of messages are associated with children in Russian propaganda?

• What emotions and values are being conveyed by using children as symbols?

• How does the portrayal of children in Russian propaganda differ from other countries’ propaganda?

The findings of this research can contribute to a deeper understanding of how propaganda works and how it affects public opinion, especially in the context of Russia’s political and social environment. Additionally, the research can shed light on the ethical implications of using children as symbols in propaganda and the potential impact on children’s well-being.

Why propaganda?

Jowett and O’Donnell proposed the most appropriate general definition of political propaganda:

“Propaganda is the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist.”

Further explanation allows us to understand that the fundamental difference between propaganda and persuasion lies in its more powerful systematic nature and, most importantly, in shaping the world’s perception and anticipation of the response.

The anticipation of response as a criterion for defining propaganda allows us to assume its deliberate creation and dissemination and assert that propaganda can exist independently of whether it elicits a response.

With sufficient information literacy among the population, propaganda will not act with enough force or not at all, meaning the expected response of the recipient will not occur. However, in this case, the absence of a response will also be considered a response, but it will indicate the ineffectiveness of propaganda.

Why Children?

Due to several factors, children are often seen as a significant target audience for state propaganda. Firstly, children are considered more vulnerable and impressionable than adults and may be more easily swayed by propagandist messages.

This vulnerability is heightened because children are still developing their critical thinking skills and are less likely to question the veracity of the information presented.

Secondly, children represent the future of a society and its values, making them a key target audience for those seeking to promote a particular ideology or agenda. By targeting children with propaganda, propagandists hope to instill specific values, beliefs, and attitudes that will shape how they think and act as they grow up, ultimately contributing to forming a particular social or political culture.

Moreover, children are often seen as trustworthy and innocent figures, which can legitimize the propagandist message. Using children as symbols in propaganda, the propagandist seeks to evoke positive emotions, such as compassion and protectiveness, to create a sense of identification and trust with the target audience.

Finally, children can be used to appeal to the emotions of adults, who are often concerned with the well-being and prospects of the next generation. By portraying children as victims or beneficiaries of a particular policy or ideology, propagandists hope to tap into the emotions of adults and encourage them to support their cause.

In summary, children are vital recipients of state propaganda due to their vulnerability, role in shaping society’s future, perceived innocence and trustworthiness, and potential to evoke emotions in adult audiences. This makes using children in propaganda a powerful tool for those seeking to shape public opinion and promote their agenda.

Why content analysis?

Content analysis is the most effective research method to analyze propaganda as a set of manifestations in communication. It allows for a detailed examination of media messages while forming a general understanding of the subject of the study.

In this research, we will use the AttackIndex service to form a study of the general information background in Russian media that features children. To do this, we created a query with the main keyword “Children” and specifying “Russia, Ukraine.”

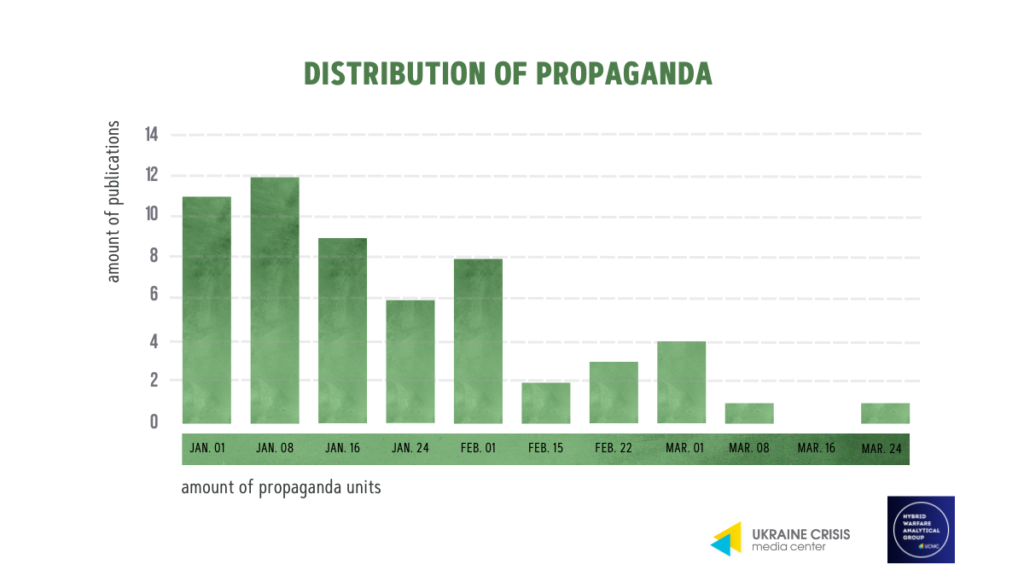

Thus, we obtained a sample of 78,402 publications from January 1st, 2023, to March 30th, 2023. The likely audience coverage reached 2,589,520 people who viewed the publications in the sample.

The report from the AttackIndex service indicated that the highest activity occurred during February 2023.

Therefore, for a more detailed examination, we will review all news articles with the tag “children” from 18-28th February 2023 on one of Russia’s most popular media outlets, Izvestia.ru. We will analyze these news articles using the following ten propaganda techniques outlined by Jowett and O’Donnell:

• Resonance

• Source Credibility

• Opinion leader

• Direct contact

• Reward and punishment

• Group norms

• Visual symbols of power

• Figurative language

• Propaganda through music

• Emotional appeal

The unit of account is the appearance of a category in the text. They can be expressed in text and visually in photo or video materials. Accordingly, if there is a mention in the text, we assign a value of “1” to that text, and if not, “0”.

Overall Overview

The first noteworthy point from the report is that the majority (64,9%) of news publications were partially or entirely borrowed. Partially, this may indicate that the dissemination of information in the Russian information field is mainly homogeneous, allowing propaganda to use it for its purposes.

The report also states that out of all the media sources collected in the sample, 5226 were marked as propaganda, while 2213 were deemed relatively objective.

All other sources were marked as subjective, non-objective, media emulators, and others (a total of 2481). Only 53 of them were identified as truly objective media. Therefore, the absolute majority of Russian media are involved in promoting Russian propaganda narratives.

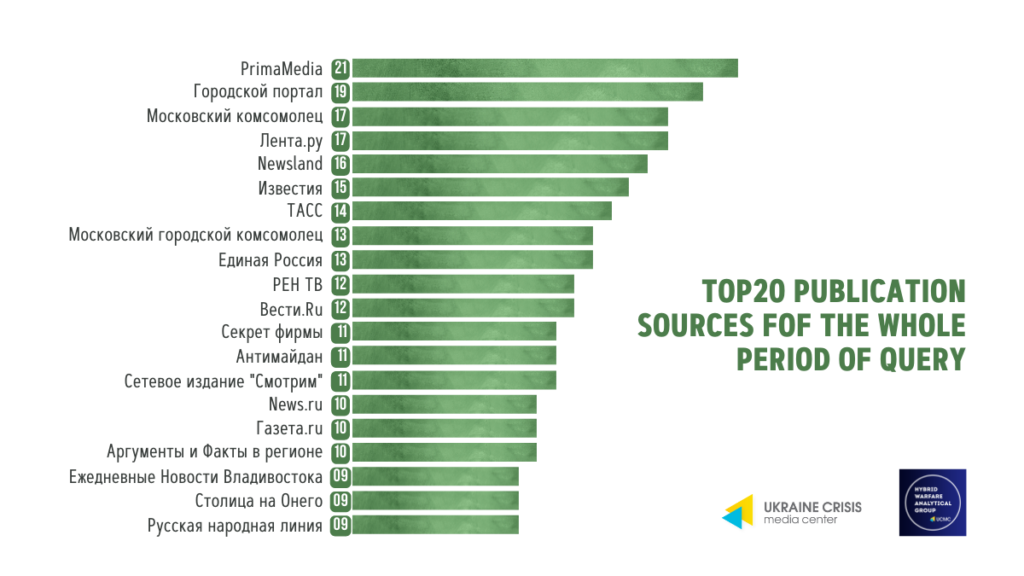

This list further confirms that the most active media in Russia covering the topic of children are primarily pro-government. For example, PrimaMedia is a large media holding company that branches in the temporarily occupied city of Sevastopol.

The online newspaper “Moskovsky Komsomolets,” in turn, constantly disseminates anti-Ukrainian stories, refers to the war as SMO, and provides a list of “foreign agents and extremist organizations” on its website for “convenience.” The same can be said of Lenta.ru, Izvestia, and TASS.

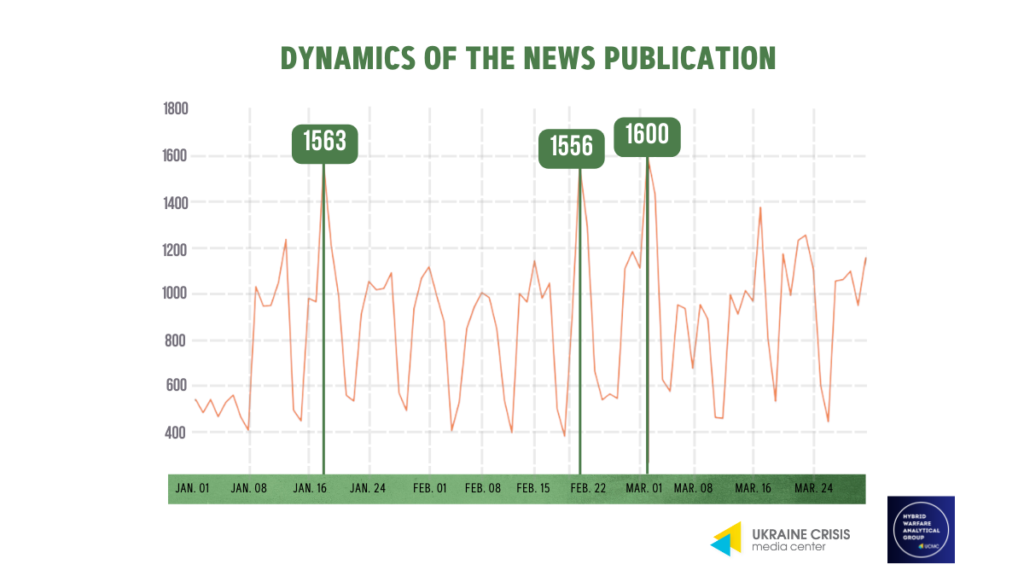

It is also important to note that according to the dynamics of the news publication, three days stand out significantly during the analyzed period when activity was at a very high level. These are January 18th (1563 publications), February 21st (1556), and March 2nd (1600 news).

The first date coincides very accurately with the tragedy in Brovary when a helicopter carrying the leadership of the Ministry of Internal Affairs crashed. The second date corresponds simultaneously with the hosting of the “Children of Asia” sports competition in Russia, which was actively covered in the news.

This date also coincides with the preparations for Defender of the Fatherland Day, in which the Yunarmiya youth organization actively participates. The third date corresponds to the day when, according to Russian media reports, Ukrainian military personnel sabotaged the Bryansk region, allegedly leading to a school bus shooting.

The Russian information environment becomes heavily saturated with publications involving children precisely when there are manipulative information triggers.

Russian propaganda, in the first and third cases, clearly positioned Ukraine as a threat to the safety of children. At the same time, the Russian regime seeks to weaponize children and legitimize itself in the second case.

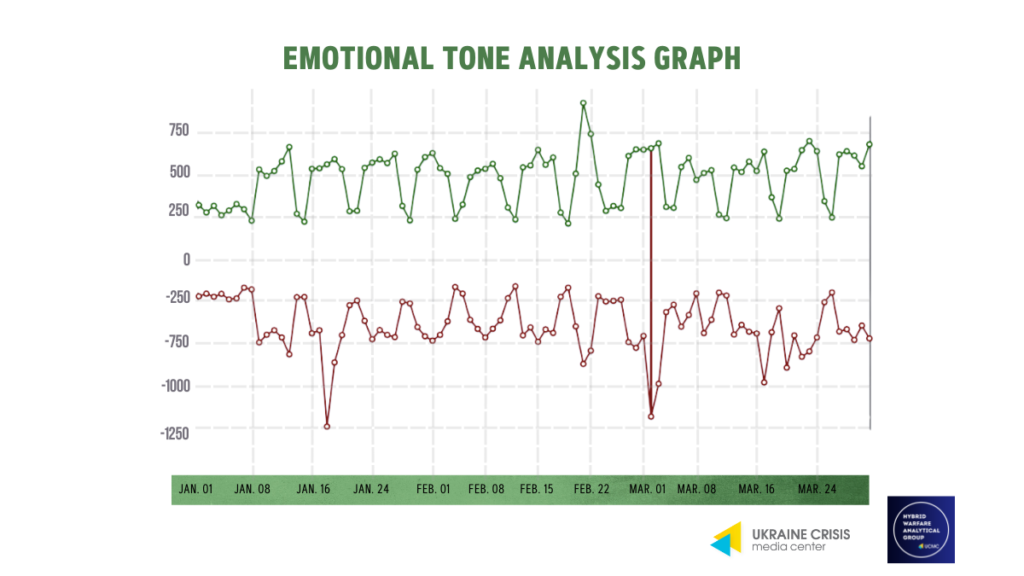

An additional argument supporting the previous statement is the correspondence with the emotional tone of the publications. The graph shows that the peaks of negatively toned responses in January and March coincide with the dates of the information triggers. Meanwhile, in February, the emotional tone of the publications regarding children reached its highest level.

It is worth noting that Russian propaganda attempted to create positive narratives simultaneously in the case of the information trigger involving the diversions. This was achieved by fabricating the myth of the “heroic boy Fyodor,” who supposedly helped save the girls affected by Ukrainians.

It would not be surprising if, over time, Russian media acknowledged this was a fabrication, just like the crucified boy in underwear.

Content-analysis of Izvestia media

From February 18th to 28th, 2023, 64 news articles were published with the tag “children.” Most of these news articles were related to criminal incidents involving children in different regions of Russia.

Additionally, the news publications were often connected to the state’s social policies. Overall, the news articles in the sample appeared to have the sole purpose of informing the population, but was everything as straightforward as it seemed?

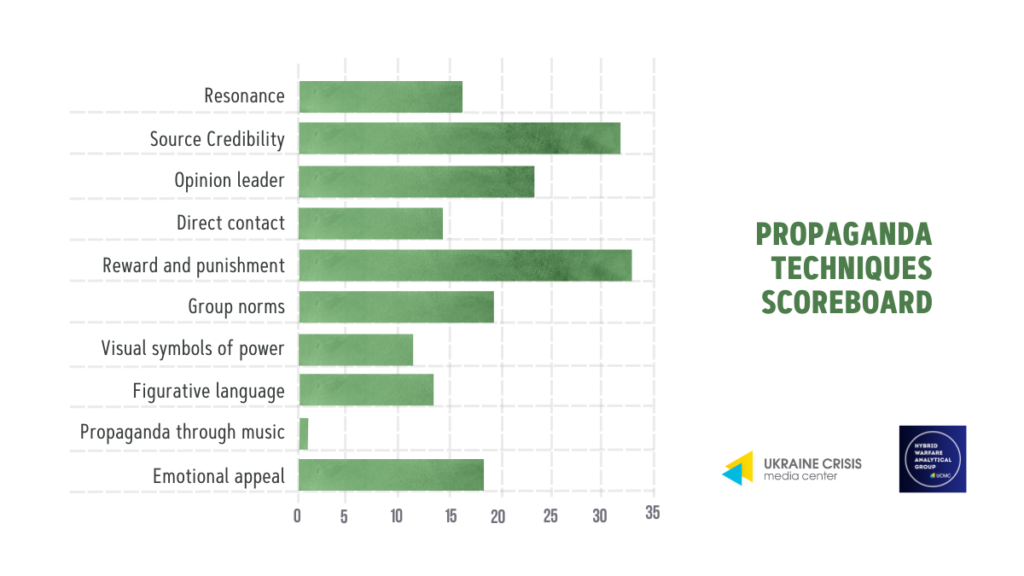

By analyzing each news article for the presence of those mentioned ten typical propaganda techniques, it was determined that out of 640 possible instances of propaganda, they were identified 189 times, accounting for 29.5% of the cases. For a news portal, the occurrence of one-third of the possible instances is quite significant.

The graph demonstrates that the most frequently used propaganda techniques on Izvestiya were “Source credibility” and “Reward and punishment” (33 and 34 instances, respectively). “Source credibility” was typically established through references to government resources or testimonies from personal media sources.

This was aimed at fostering greater trust in the media. On the other hand, “Reward and punishment” was manifested following the published materials. Thus, in the criminal chronicles, there was often an emphasis on individuals being punished by “brave police officers.”

Additionally, the methods of “Opinion leader” (24 instances), “Group norms” (20 instances), and “Emotional appeal” (19 instances) appeared approximately 20 times each. “Opinion leader” was manifested through appealing to various experts and regional political leaders. “Group norms” shaped the perception of community and shared mentality within Russia.

On the other hand, the overall emotional tone of the news articles created a specific emotional background, making it easier to influence the population. Thus, quite often, “Emotional appeal” was accompanied by the technique of “Figurative language” (10 instances out of 14 possible).

This graph demonstrates the distribution of publications based on the number of propaganda instances found within them. It shows that out of the 64 publications, only 11 news articles had no detected instances of propaganda. Therefore, propaganda manifestations were present in 53 publications, accounting for 82.7% of the cases.

Notably, the number of publications containing 1 to 4 instances of propaganda is 35, which accounts for 55% of the cases. This suggests that the intensity of propaganda on this resource is low.

However, in 28% of the cases, there are 5 or more instances of propaganda, including 4 publications with 7 instances and 2 with all 10 propaganda markers.

Here are a few headlines from Izvestia, an online media outlet, with the most evident propaganda manifestations:

- Lvova-Belova expresses confidence in Russia’s bright future following Putin’s message;

- Poles outraged by refugees from Ukraine walking around with Nazi symbols;

- Ukrainians in Spain attempted to disrupt a rally in support of Donbas;

In all these publications, the techniques mentioned above and basic logical manipulations are used. In combination, they deceive the reader and create a negative perception of Ukrainians and Ukraine as a country.

Classic manipulations such as “Nazi symbols,” “killing of the people of Donbas,” and “Russia’s concern for children” are present here. It is important to note that arrest warrants have been issued by the International Criminal Court for Lvova-Belova and Putin themselves.

Summary

1. Types of Messages Associated with Children in Russian Propaganda: Russian propaganda utilizes various techniques and logical manipulations in association with children. These messages often aim to deceive the readers and create a negative perception of Ukrainians and Ukraine. They include references to Nazi symbols, the alleged destruction of the people of Donbas, and Russia’s supposed concern for children.

2. Emotions and Values Conveyed through the Use of Children as Symbols: The portrayal of children in Russian propaganda evokes emotions of sympathy, fear, and nationalism. Children are used as symbols to invoke a sense of empathy, victimhood, and patriotism among the audience. The propaganda aims to strengthen support for the Russian government’s policies by highlighting their vulnerability and emphasizing their connection to the nation.

3. Differences in the Portrayal of Children in Russian Propaganda: The portrayal of children in Russian propaganda differs from that of other countries propaganda in terms of the specific narratives and techniques used. Russian propaganda frequently combines emotional appeal, source credibility, reward and punishment, opinion leader endorsements, and appeals to group norms. The manipulative tactics employed alongside these techniques contribute to a distinct portrayal of children, often presenting them as victims or heroes in the context of geopolitical conflicts.

These conclusions provide an overview of the messages associated with children in Russian propaganda, the emotions and values conveyed through their use as symbols, and the differences observed compared to other countries’ propaganda.