Russian blogger Maxim Katz is searching for Ukrainians to participate in his new ‘Voices of War’ project, which seeks to gather personal stories from those who have been affected by the ongoing conflict.

However, not everyone is convinced of Katz’s motives. Otar Dovzhenko, a media expert and chairman of the Independent Media Council, has criticized the project as Russian propaganda aimed at absolving the Russian nation of responsibility for its aggression against Ukraine.

Dovzhenko argues that initiatives like ‘Voices of War’ are part of a wider campaign to portray Russians as victims and equate their suffering with that of Ukrainians. He believes that Ukrainians must speak out against such manipulations and make it clear that they are offended by them telling how these ‘projects’ are “Russian propaganda. Not Kremlin propaganda, but Russian propaganda”.

Dovzhenko also notes that while initiatives in Ukraine and abroad are often analyzed by the Kremlin media, there is little scrutiny of non-Kremlin Russian media. He suggests that a closer examination of these media outlets would reveal that many of them are also promoting a version of Russian propaganda. “These are cynical manipulations, and we must constantly debunk them,” tells Dovzhenko.

Maxim Katz is a Russian politician and public figure, author of the Maxim Katz YouTube channel.

The Institute of Mass Media tells how, In October 2022, Maxim was added to the database of the ‘Myrotvorets’ (Peacekeepers) website for promoting “Russian fascist Nazism and chauvinism”, considered a threat to Ukraine’s security because of his posts on social media.

Here are a few reminders:

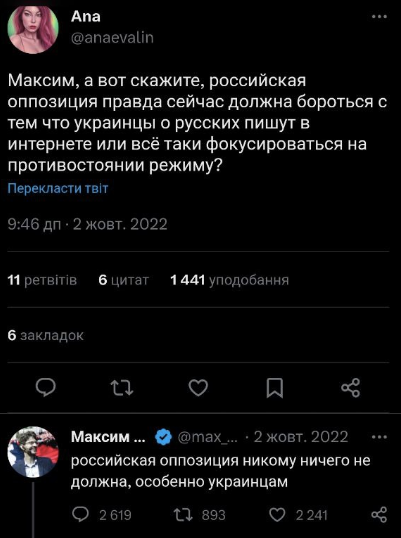

Russian Opposition

“Maxim, tell us, does the Russian opposition really have to fight with what Ukrainians are writing about Russians on the internet or instead focus on opposing the Russian Regime?” a Twitter follower asks. “The Russian Opposition has no obligation to do anything for anybody, especially Ukrainians,” he responded.

We can infer from this conversation that Maxim does not necessarily support Ukraine or prioritize the issue of Russian aggression against Ukraine in his work, implying that he does not believe the Russian opposition has any obligation to support Ukrainians or engage in online debates about Ukraine-related issues.

It’s also worth noting that the Twitter follower’s question assumes a clear distinction between opposing the Russian regime and opposing Ukrainians’ negative portrayals of Russians on the internet. Maxim’s response does not directly address this assumption, but it begs the question: why launch an initiative involving Ukrainians to hear their war stories if he has no intention of prioritizing the Ukrainian narrative over Russia aggression?

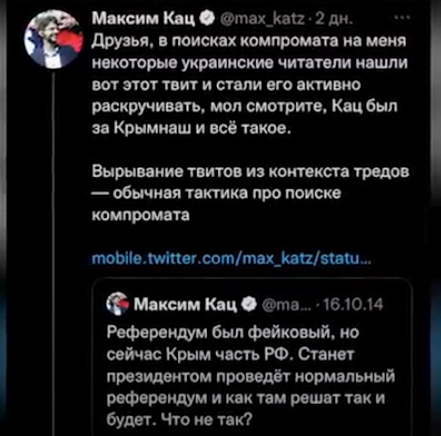

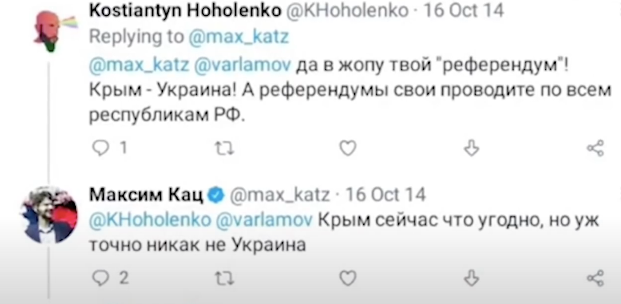

Crimea

We can infer from this conversation that Maxim is anti-Ukraine and supports Russia’s annexation of Crimea. He admits that the referendum was rigged, but he still recognises Crimea as a part of Russia. This indicates that he is opposed to Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Furthermore, his response to the suggestion that a referendum be held in Russian Federation republics rather than Crimea demonstrates a lack of interest or support for democratic processes in his country. Instead, he simply reiterates his belief that Crimea is no longer part of Ukraine.

“It is true that there was no significant protest, though Crimean Tatars attempted to protest, but the lack of large-scale protests indicates that the population was not so opposed to the regime that they would risk their lives.” Maxim says in a YouTube episode dedicated to Crimea.

The mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944, which affected an estimated 191,044 people, naturally, made significant protests difficult. During this time, the Soviet Union imposed a “Russification” policy on the peninsula, prohibiting the study of Tatar, erasing ancient Tatar names, burning Tatar books, and destroying their mosques.

Maxim is incorrect in claiming that the absence of mass protests in Crimea during Russia’s annexation demonstrates that the population was not opposed to the regime. The historical context of the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944, as well as the Soviet Union’s Russification policy, played a significant role in shaping the political landscape in Crimea. These actions made it difficult for the public to organize large-scale protests. The fact that more Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea does not necessarily imply that they supported Russia’s annexation. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 violated international law, and the peninsula remains a part of Ukraine.

Manipulation and Lies

A prominent debunker of Maxim’s claims, Vitalik Gordienko, recently criticized Maxim’s YouTube videos about Russian security services. Maxim often dismisses well-documented acts of the FSB, such as attacks on buildings in the 2000s, as conspiracy theories due to a lack of concrete evidence. However, Gordienko finds it strange that Maxim records videos presenting these claims as possibilities. He points out that it is difficult to believe Maxim’s skepticism when Putin has already been responsible for the destruction of thousands of Ukrainian homes.

Gordienko goes on to recount how on the 16th day of the war, Maxim once again repeated Russian propaganda, claiming that the Russian military had no intention of destroying cities, and that any damage to civilian infrastructure was merely a ‘mistake.’ Gordienko expresses disbelief at Maxim’s position, highlighting the evidence to the contrary

Here is a photo of Russia’s mistake as believed by Maxim, which shows the entire inhalation of a Ukrainian city 18 days after Russia’s large-scale war on Ukraine began; a mere two days after Maxim’s statement.

Despite these criticisms, Katz’s ‘Voices of War’ project may still attract many participants, including some Ukrainians who are eager to share their stories with a wider audience. The project highlights the ongoing complexities and tensions between Ukraine and Russia, and the challenges of navigating these issues in the media landscape of the region.