Written by Matt Wickham, HWAG/UCMC analyst

With the Paris Olympic Games approaching, the Kremlin’s propaganda choir continues to sing innocence and foul play for the IOC’s decision to exclude Russian athletes from the 2024 games. The Kremlin and its propaganda stooges have pushed the narrative that sport should be and always has been, beyond politics. Any blurring of these lines, they say, violates international sporting principles and jeopardizes the effectiveness of international institutions – a classic narrative of Russian propaganda. The credibility of this ‘separation’ rhetoric, however, would be far more compelling if Russian athletes (past and present) actually kept their sporting careers separate from politics.

The Kremlin has tokenized their athletes to garner support for Russia’s genocidal war on Ukraine, particularly for reaching segments of the Russian population that standard propaganda struggles to influence, not to mention to make it the people’s war, not just Putin’s.

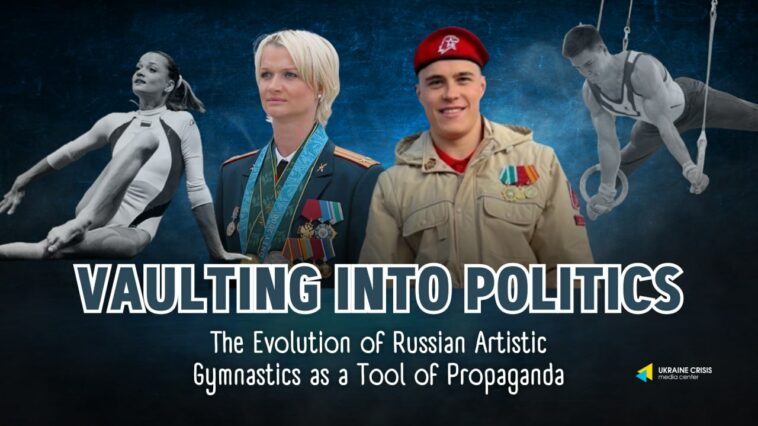

Gymnasts, both past and present, have been no exception. In this article, we aim to analyze these ‘tokenized’ gymnasts and their rhetoric, which blends sport with politics, justifying the IOC’s decision to keep Russian gymnasts out of the Olympic Games. In addition, we will prove how the state has integrated itself so deep within the gymnastics apparatus by singling out several Russian gymnastics champions, leaving the rhetoric that ‘sport beyond politics’ is nothing more than a Russian fallacy used to serve its narrative.

Artistic Gymnastics – A Soviet Delicacy?

A sport beloved by Russians for its fusion of grace, reminiscent of elegant Russian ballerinas, and inherent strength, along with its historical dominance during the Soviet Union, instilled a sense of pride in the Soviet people during times of despair and hardship. The success of Soviet gymnastics is an embodiment of how Russians wish to (and do) consider themselves on the international stage – a cultured, powerful, and graceful nation capable only of winning. The sport’s achievements were pivotal in shaping Soviet national identity, leading to a certain level of arrogance and an inflated self-perception of the ‘greatest nation on earth.’

Russia, however, has struggled to reclaim its former position as an Artistic Gymnastics powerhouse over the last two decades. While it had produced stars such as Khorkina, Mustafina, and Nemov, and current champions such as Nagornyy and Dalaloyan, it had failed to sweep the medals as once did for decades. Like the Russian Federation, the Union played a role in identifying and developing young gymnastics talent. Those with a promising future were frequently recruited into specialized sports schools, where they received rigorous training under the supervision of the state, such as the CSKA (the state-controlled militarized club of Russian elite athletes).

Gymnastics As a ‘Soft Power’

In the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, gymnastics served a variety of political purposes, with its first national federation established in 1883 by founding member and well-known author, Anton Chekhov. The sport gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, being, then, viewed by authorities as a means to improve physical fitness and prepare individuals for military service. However, as time passed, the legacy of Artistic Gymnastics, which combined athleticism and artistic expression, became a powerful symbol of the Soviet system’s strength and excellence on the international world stage.

During the USSR athletes such as Larisa Latynina (Russian), Stela Zakharova (Ukraine), and Olga Korbut (Belarus), exemplified the nation’s prowess and marked the era of the USSR’s world dominance, albeit in sport. These victories were then (much like today) used for propaganda, highlighting the socialist system’s superiority and ‘untouchableness.’ Gymnastics, therefore, became a form of “soft power” used to build or break diplomatic bridges whilst conveying political messages.

The Soviet Way

Gymnastics, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, saw Russia churning through huge numbers of female gymnasts to keep up with the era of USA dominance in the sport. Russia’s rising stars’ careers were cut short due to devastating injuries from overtraining, burnout (even before reaching senior competition age – 16), or the athletes frankly becoming disenfranchised with the sport. This was due to its grueling and abusive toll on the body and mind from both the sport and the trainers. The impact of being put through arduous training with little regard for psychological or mental health, all for the sake of victory, no matter what – this is the Soviet way. Interestingly enough, much like Russia’s approach in war – throw all you’ve got at it with little regard to the human factor in the hope of a win—a mere resource. It is a strategy, however, and sometimes successful, but one that takes into little, if not no, consideration of the human factor.

Puberty was often deemed a career-ending impediment for female gymnasts during the Soviet era due to complications in the gymnasts’ coordination and weight, making many skills that much harder for a taller, heavier athlete. Soviet coaches, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, took advantage of smaller, younger athletes. They created a culture in which coaches exercised control over every aspect of athletes’ lives, including diet and the use of drugs to suppress puberty.

In Soviet gymnastics, competition was always fierce and a dirty battle for dominance, especially for the chance to fight for Olympic gold – a rare ticket for prestige and a luxury life in the times of struggle in the USSR for both the athlete and coach. But the talent pool was vast, and only a select few were chosen to compete, making the pressure intense not only for the athletes but also for the coaches. This pressure led to coaches abusing their position of power and intimidating the gymnasts before elite competitions.

Yelena Mukhina wanted to retire from sports a year before she suffered a life changing spinal injury, yet feared her coaches reaction and knew she had no other choice but to continue. “I couldn’t stand it any longer. Not so much the physical as the psychological strain.”

In 2020, Svetlana Khorkina, former multi-olympic medalist and vice-president of Russian Gymnastics Federation, was asked about the latest charges of abuse in gymnastics (worldwide), to which she turned her nose up to the allegations, claiming that those who did not speak up earlier were merely seeking self-promotion.

“Why didn’t they sue? It’s just self-promoting. Ugh. Such questions don’t even arise with normal coaches and athletes – they understand on their own how they need to behave in training and observe the rules….Then why did they stay silent for such a long time? How little respect did they have for themselves [to stay silent]?”

Svetlana Khorkina

Her answer shows how her Soviet sporting indoctrination is deeply ingrained in her approach to leading Russian gymnastics, thus downplaying Mukhina’s tragedy, the Soviets’s gymnastics ‘sweetheart’ Olga Korbut’s sexual abuse, and all other gymnasts abused by the sport. This, therefore, raises concerns about how abuse and psychological well-being are being ignored and downplayed in Russian gymnastics for the sake of creating a champion.

Moreover, just like any other sport, gymnastics evolves and necessitates significant funding to produce champions. With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, a negative impact on sports investment was felt, and the challenge was exacerbated by the dispersal of athletes who had previously competed for the union, then, overnight, competed for other nations. Russia was therefore faced with the task of rebuilding its gymnastics legacy. But it wasn’t all dire for the federation… Rebuilding comes with its perks; the state control could tighten its grip, and so it did.

Khorkina the ‘Great’

Svitlana Khorkina, married to Oleg Kochnev, a former general in Russia’s Federal Security Service, suffered a loss to the United States’ Carly Patterson in the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, All-Around (AA) title. Following this defeat, a classic Russian conspiracy theory emerged, showcasing a reluctance to accept defeat and the belief in a premeditated coup. Khorkina expressed her frustration, stating:

“I’m just furious. I knew well in advance, even before I stepped on the stage for my first event, that I was going to lose. Everything was decided in advance. I had no illusions about this… I practically did everything right, yet they just set me up and fleeced me… I think it’s because I’m from Russia, not from America.”

Svetlana Khorkina

This was in 2004, when Russia wasn’t considered the enemy as it once did throughout the Cold War and years before Russia invaded Georgia in 2008. But still, the mentality that ‘everyone is against us, and it is not fair’ deeply rooted in the Russian and Soviet propaganda machines was present. And so started the era of Russian gymnastics, believing the international sporting system was out to get them, flawed, and worked only in the interest of the Americans – a rhetoric shared by modern-day propaganda.

Colonel Khorkina

Khorkina’s transition from gymnastics to politics exemplifies the undisputed connection between the two worlds. From 2007 to 2011, she served as deputy chairperson of the state duma’s committee for youth affairs. During this time, she met Alina Kabayeva, a former Rhythmic Gymnastics champion, rumored to be Putin’s long-term lover.

Later, Khorkina took the lead in Russia’s ‘Yunarmia’ program, a youth initiative ostensibly aimed at instilling patriotism but, in reality, served as a means of indoctrination. Once her term as a state deputy ended in April 2011, Khorkina remained in politics, holding a somewhat murky position under the wing of the Administration of the President of the Russian Federation, for whom she doesn’t attempt to hide her fondness.

In 2016, she was appointed first deputy head of the ‘Central Army Sports Club’ (CSKA), a Ministry of Defence club founded in 1923, and as the vice president of the Russian Artistic Gymnastics Federation. She publicly defended Russian gymnast Ivan Kulyak, suspended for sporting the letter Z during a World Cup competition on his leotard.

“I like how he thinks and acts. If he did it, he must have had a good reason. That’s just how he sees things.”

Svetlana Khorkina’s comments on Kulyak’s wearing of the military Z symbol

Suppose there were doubts about Khorkina’s ability to separate sports from politics…In that case, one must look no further than the military parade she attended as a colonel in the Russian army, proudly wearing her military costume adorned with her numerous Olympic medals. This visual representation emphasizes her deep integration into both the military and sporting spheres, demonstrating that the rhetoric of ‘sport beyond politics’ is far from realistic for Khorkina and, thus, the Artistic Gymnastics enclave of the Russian Federation.

Nikita Nagornyy

Nikita Nagornyy, part of the 2020 Olympic champion team in Tokyo, has ventured into the political arena since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Their 2020 victory marked a significant moment for Russian male artistic gymnastics, ending a drought of gold medals that had persisted since the turn of the millennium. Nagornyy has since become an outspoken athlete, falling under Western sanctions after entangling himself in the political propaganda processes of the federation. Yet it seems this is precisely where he wants to be.

Following his Olympic success and Russia’s gymnastic resurgence, Nagornyy’s stance on the cry of ‘unfairness’ directed at Russians competing without a flag drew attention from the Kremlin. Subsequently, he activated a public Telegram account on February 27, 2022. Yes, just three days after Russia launched its war on Ukraine. A coincidence? This lends the impression that someone ‘from above’ ordered Nagornyy to join the propaganda front, posting pro-war and Kremlin-pushed posts. These posts include meetings with politicians, interviews with Z symbols in the background, and pictures of his visit to wounded soldiers who participated in the so-called ‘SMO.’

Chief Nagornyy

Nagornyy’s support for the war is intertwined with his past, his military conscription service, and his belonging to the state-controlled CSKA club. This club, home to many other Russian athletes wanting to compete at the 2024 games, provides ‘humanitarian aid’ to those at war (delivered by Military SUVs sporting the Z logo).

The CSKA approach exposes athletes early on in their careers to the state’s values and ideologies – unwavering loyalty instilled during gymnastics training under the guidance of Kremlin-backed trainers from a young age. This, therefore, underscores the depth of his commitment to the state. Nagornyy questions why young Russian men are disenfranchised by the idea of serving in the Russian military; he continues :

“I used to be in the army. Every man has to go through it at some point in his life. And now, more than ever, our youth require such movements.”

Nikita Nagornyy

Nagornyy, who is currently training for Paris, over the line of ‘sport’ and into the world of Russian politics.

Moreover, to prove the point as to why allowing Russians to compete, even under no flag is not enough as, Nagornny told,:

“They took away our hymn and flag, attempting to label us as not Russians, but we nevertheless fought for Russia because it is our homeland and the hym is in our hearts.”

Nikita Nagornyy

Rumors of Nagornyy entering politics, possibly as a State Duma deputy, suggest a trajectory set in motion, fueled by his support for the war on Ukraine and his role as the head of the youth group “Yunarmia.” While Nagornyy denies his immediate political aspirations, his actions, and affiliations point toward a future in Russian politics, reinforcing the notion that, for him, and therefore the current Russian gymnastics apparatus, sport and politics are intertwined.

To Summarize

Russia uses major sports and athletes not only for sporting purposes but also to spread its influence on the world stage, put pressure on international opinion, and raise its profile in the world through lies, manipulations, and a frenzy of patriotic propaganda.

The Russian leadership, like the Soviet propaganda machine, uses the sporting achievements of past greats such as Irina Rodnina (figure skating), Anatoly Karpov (chess), Vyacheslav Fetisov (hockey), and Khorkina (artistic gymnastics). Simultaneously, Russian ideologues are transforming these athletes into moral authorities for young people. They have become the Kremlin’s mouthpieces by being given high-ranking positions in the State Duma, international sports federations and high salaries. The Kremlin appropriated their sporting authority and high sporting achievements and uses them to zombify its own population and lobby on international platforms for a narrative about the unfair punishment of Russian sport.