One-fifth of Ukraine’s lands are under temporary occupation. And although everyone believes that these territories will be returned, it is too early to say when it will be – this war will not end quickly. What should people do if they are kept hostage? Of course, run at the first opportunity and at their own risk.

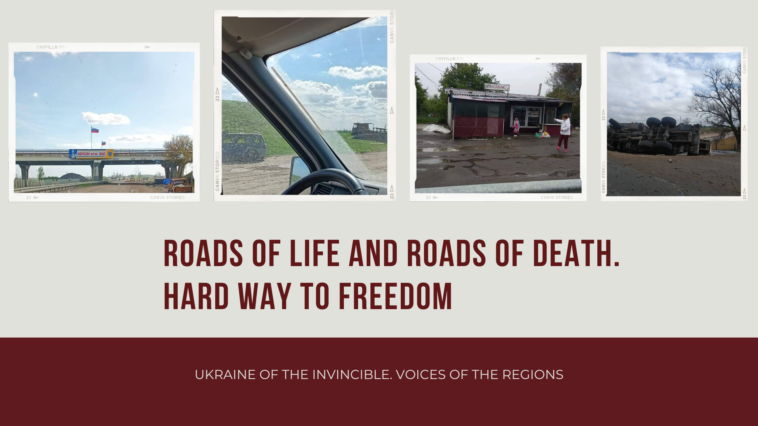

Roads of life and roads of death

Despite the fact that Russian occupiers are blocking exits from Kherson region and there have been no “green corridors” from the region for more than three months of full-scale Russian military invasion, people continue leaving their homes en masse.

There were several unofficial evacuation corridors or, as they are often called, “roads of life” from the south of Ukraine. First, people from Kherson region broke into Mykolayiv through Oleksandrivka of the Stanislavska territorial community. The last time occupiers allowed this passage was on March 28.

Later people managed to find another way – through Snihurivka of Mykolayiv region. They were able to take that road from April 2 to April 20. Then the route became much longer – it went in the direction of Kryvyi Rih through Beryslav and Davydiv Brid. The last time it was used was on May 13. However, people tried to pass there in the following days and for some it became a “road of death”: in the evening of May 17, the Russian military fired Grad missiles at a convoy of civilian vehicles in the vicinity of Davydiv Brid. At least three people were killed and a lot of people were wounded.

After that, Zaporizhzhia region is perhaps the last possible way to enter the territory of free Ukraine. It was that way that a resident of one of the villages of the Kakhovka territorial community chose at the end of May.

“There were 12 people in our car, six of them children, including children with disabilities. In front of Vasylivka in Zaporizhzhia region, the Russian military held us for 24 hours. They were drunk and often fired into the air. In the morning another “shift” came and our drivers managed to agree with the occupiers that they would let us through for money. We paid 100 hryvnias per car and they let us through. Then we passed two more checkpoints, but at the penultimate they kept us again for over 24 hours and also collected 100 hryvnias per car. At the last Russian checkpoint, they simply noted down how many women, men and children were in a car. It was very scary to drive; we heard repeated shelling at night. On the way to the controlled area and along the forest belts we saw many mines. Our way to freedom took us three days. When we first saw our soldiers, we were very happy. They helped us with an escort to Zaporizhzhia, gave us food and organized a night stay,” she said on condition of anonymity.

Extortion at Russian checkpoints is common. For the most part, they demand cigarettes and something to eat. But often they take valuables and even money. There were cases when the Kherson residents had to pay $ 5,000 per person for passing through enemy checkpoints.

“Now I can’t go to the Ukraine-controlled area. I was held captive for half a month and tortured for being a former Ukrainian serviceman, and now my whereabouts are being closely monitored. The occupiers told me I could leave Kherson region, but they demanded $ 3,000. I don’t have such money,” said a resident of the region, whose name we cannot reveal for security reasons.

“A few of my acquaintances had money demanded at Russian checkpoints. Judging by the accent, they were Chechens. Fortunately, my acquaintances managed to leave all their “stash”: they used cigarettes and food to buy off. But one car in their convoy was unlucky: people had to pay $ 400. There were cases when Russians took away cars at checkpoints,” an administrator of one of the chat rooms on social networks dedicated to the evacuation from Kherson region said on condition of anonymity.

According to the deputy of the Kherson city council Yuriy Stelmashenko, the road on which people leave Kherson and Kherson region isn’t coordinated with anybody. They all decide to leave at their own risk.

He says that people’s safety on the route cannot be guaranteed, as the whole territory of the region has been an active theater of military operations since February 24. But Yuri Stelmashenko understands why people are leaving, especially after we learnt about the Russian occupiers’ crimes against civilians in Kyiv region, Kramatorsk and Mariupol.

For some people, the mass desire to leave Kherson region has become a way to profit from the misfortunes of others. Since not all have their own vehicles, in March, charlatans began appearing in numerous social media groups, demanding prepayment for transportation across the front line. After people transferred the money, they disappeared. If you are lucky and manage to find a reliable carrier, you will have to pay from UAH 5-6 thousand per person for travel from Kherson to Mykolayiv or Odesa. Before the war the cost of travel from Kherson directly to Mykolayiv did not exceed UAH 100.

As for the shelling near Russian checkpoints, it happened not only in May, but in all previous months.

“On March 26, we managed to drive through Oleksandrivka. I was driving in a convoy of 10 cars. All with children. Everyone managed to slip through. But it was a real challenge – “life or death.” On some sections of the road, just on the front line, we had to drive at a speed of 130 km/h. A projectile fell and exploded about 30 meters away from my car. I drove blindly through a totally black cloud of smoke. But those who followed us on the same route were unlucky. Many cars came under fire. I know of at least a few victims. Other drivers said that in the following days they literally had to drive over the top of dead people. They said that the road reminded them of an open-air morgue. I think that’s when the road was closed to traffic,” a resident of Kakhovka district said on condition of anonymity.

The family of a teacher from the Kakhovka territorial community also came under fire.

“We tried to drive to Snihurivka for several days. We were kept near checkpoints for a long time. Then we realized that Russians needed us there as a human shield. So that our soldiers could not fire on their positions and counter-attack them. Later, as we approached one of the bridges, the Russians hit it. We miraculously survived,” she said on condition of anonymity.

Hard way to freedom

A large number of residents of the region managed to escape to the government-controlled area through the temporarily occupied Crimea.

“After the Russian military abducted most of my friends and acquaintances, I realized that it would soon be my turn. There was no time to wait and I decided to leave the next morning. But in those days all exits from Kherson region were blocked, so I had to go through Crimea. I paid 1,500 hryvnias to the minibus driver for the trip from Kakhovka to the administrative border with the peninsula. There was another bus waiting for us, which was to take us to Warsaw for $ 600. The trip was very difficult and took us almost 4 days. We drove through Krasnodar, Rostov-on-Don, Moscow and Pskov regions. We got out at the Ubylinka checkpoint, crossed the border with Latvia, where another bus was waiting for us, which took us directly to Warsaw. From there I went to Lviv,” a resident of Kakhovka said on condition of anonymity.

According to him, Russian FSB officers interrogated him and all other men for 12 hours at the Crimean “border” and at the Ubylinka checkpoint.

“Most of the time we were just sitting and waiting for our turn, but in general, Russians held us for a long time. They asked me whether I had relatives and friends in the territorial defense, SBU, local authorities, among ATO veterans, the military. They stripped me from neck to waist, checked my things and a mobile, asked about all the contacts in it. All FSB officers wore balaclavas and did not show their faces. One of them asked me: “Why are so many men leaving Kakhovka? Only today we have checked 1,700 persons.” I replied that I did not know the reasons for this. And he said to me: “You, Kakhovka residents, are so interesting! You all are giving almost the same answers to all questions. And almost all have equally clean phones.”

But most often they mentioned the guys from Kopany, Mali Kopany rather than Velyki Kopany. They said that they were “the most interesting” because they had “a lot” in their phones. There were cases when they found some photos with the Ukrainian flag in the mobiles. They hassled those men the most, in particular, one teacher from the Tavriysk city community,” he said.

While the occupiers continue to terrorize Kherson region inhabitants and demolish some settlements, people continue to look for opportunities to leave for the government-controlled area.

“All my friends and acquaintances have already left the city. Kakhovka seems dead, and the streets so dear to me from my childhood, seem foreign to me now. But we can’t leave, because our old mother stays here. She simply will not endure a difficult trip either through Crimea or through the front line. If we have to die, we will die in our hometown,” said Kakhovka resident Valentyna, who wished to remain anonymous.

Spouses Olena and Valentyn Bilozorenko could not leave either. They refused to abandon their goat farm in Stanislav. Despite fierce fighting and constant shelling around the village, they continue to make cheese and take care of their farm. And wait for the guests. After our victory.

Oleh Baturin, journalist, Kakhovka, Kherson region

01.06.2022

The material was created under the joint project of Ukraine Crisis Media Center and the Estonian Center for International Development with the financial support of the US Embassy in Kyiv and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Estonia.