President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko (left) and Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople.

This week the President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko addressed the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, the spiritual leader of the world’s Orthodox Christians, requesting autonomy for Ukraine’s Orthodox Church. Earlier leaders of two Ukrainian Orthodox Churches addressed the Patriarch with the same request. On April 19, the Ukrainian Parliament voted in support of the President’s respective initiative. Should the Patriarch agree, the so-called Ukrainian “pomisna” Orthodox Church (Ukraine’s own independent Orthodox Church or the national Orthodox Church) can be established, the issue has been subject to public discussion for the past quarter-century since Ukraine became independent. UCMC explains what this step would mean for Ukraine, why the issue is also a political one and, what one may expect in the future.

What is Ukrainian Orthodox Church and why Ukraine needs it? The Ukrainian Orthodox Church is to unite all Orthodox believers in the country and is being created based on the territorial principle. A local church is juxtaposed with the world one, it becomes independent and self-governing in the territory of a certain state and usually coincides with the administrative division and the borders of the state. Ukrainian politicians advocate for the need to have the local Orthodox Church by saying that Orthodox believers are longing for unity as well as emphasizing the need for Ukrainians to consolidate. At the same time, a political component is obvious here. Despite the constitutional separation of the Church and the state, the Church is actively taking part in Ukrainian politics. It became evident back in 2004 when priests of one of the confessions – the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate – were encouraging people to vote for Viktor Yanukovych, while priests of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate, the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church and Ukraine’s Greek-Catholic Church supported the Orange Revolution. Today, when Russia is waging the war against Ukraine, Ukrainian Orthodox Church would be expected to weaken Russia’s impact upon Ukraine.

History of the problem. The creation of Ukrainian Orthodox Church has been discussed for a quarter of the century, since the 1990s. A considerable part of the church leaders, politicians, and religious experts are convinced that the way to Ukraine’s own unified Orthodox Church goes through the Constantinople Patriarchate (based in Istanbul). The Ukrainian Church used to be formally subordinated to it before 1686 when the Patriarch of Constantinople Dionysius agreed to have its jurisdiction transferred to the Moscow Patriarchate (based in Moscow). According to some historians and experts in religious studies, the decision was approved with some of the canons violated. That’s why in 2008 the then President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko invited the Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople to Kyiv bringing up the possibility of granting Ukrainian Orthodox Church an autonomy from Moscow. During his visit, Bartholomew made no concrete promises as he was trying not to spoil the relations with the Russian Orthodox Church – world’s biggest and most powerful Orthodox church. In 2015-2016 former Ukrainian presidents Viktor Yushchenko and Leonid Kravchuk made at least two private visits to Istanbul to meet the Patriarch. Finally, in 2016 the Ukrainian Parliament approved an appeal to Bartholomew calling “to recognize invalid the act of 1686” as well as to grant autocephaly to Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

President Yushchenko (left), Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople (center), and President Kravchuk

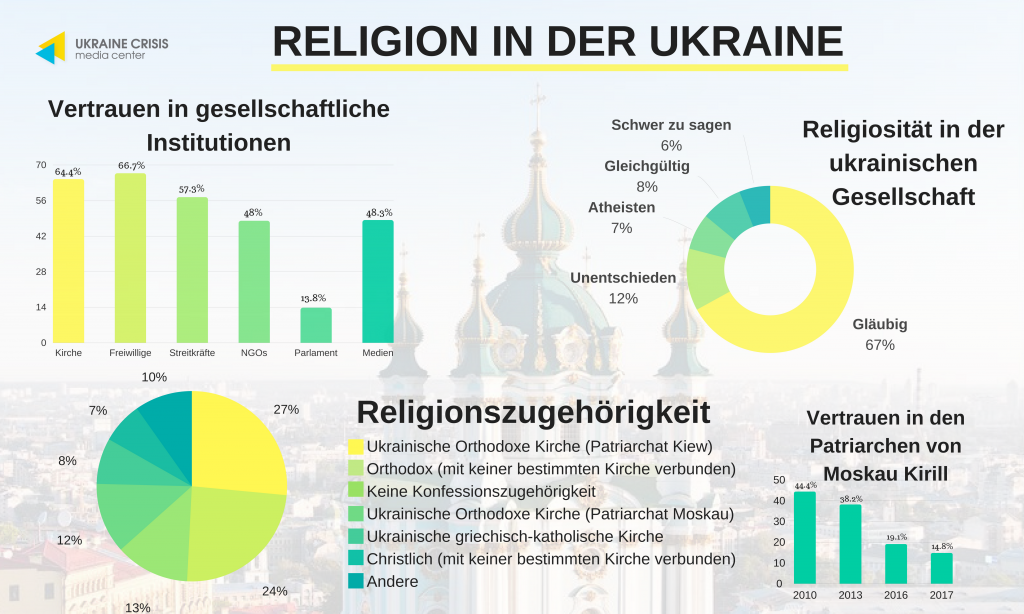

Why is the church issue important for Ukraine? Being a country with the long Soviet past, where religion was proclaimed “the opium of the people” and was something that the communist regime was violently fighting against, Ukraine got the freedom of religion only after it became independent in 1991. Opinion polls of the recent years produced convincing results demonstrating that church is one of the social institutions that enjoy the biggest trust by Ukrainians. Thus, according to an opinion poll by the Razumkov Centre (2017), 66,7 percent of respondents trust volunteers, 64,4 percent – the church, and 57,3 percent – the Army. The number of people trusting the President is almost 2,5 times lower (24,8 percent), trust in the Government and in the Parliament is even smaller (19,8 and 13,8 percent respectively). The above figures demonstrate the political capital church possesses in Ukraine. The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians (61,7 percent) consider themselves believers (61,7 percent), 2,5 percent are atheists, the number of non-believers slightly exceeds four percent, 8,2 percent are indifferent to religion.

Churches in Ukraine: what are they? There are numerous denominations represented in Ukraine, with Christianity, Islam, and Judaism co-existing. But the most widespread religion is Orthodox Christianity. At the current moment, there are six Christian Churches in Ukraine – the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (12 percent of population declared adherence to it), the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate (26,5 percent), the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church (1,1 percent), Greek-Catholic Church (7,8 percent), Catholic (1,1 percent) and Protestant churches. Many Ukrainians (24 percent) identify as Orthodox Christians not affiliated with any particular church. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate headed by Metropolitan Onufriy is formally considered to be autonomous, while it actually keeps close ties to the Russian Orthodox Church in terms of organizational and administrative matters, canons, and ideology. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate headed by Patriarch Filaret emerged in 1992 after part of the clergy left the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate in pursuit of independence from the Russian Orthodox Church. Its canonicity or “lawfulness” has not been settled yet, as the canonical churches do not recognize it as official. Currently, in Ukraine, it’s only the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate that is canonical, while the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church are self-proclaimed and thus considered non-canonical. Co-existence of three Orthodox Churches has never been peaceful as they have always been competing with each other for believers, support from the authorities, and financial resources. Moreover, the political dimension is crucial in this rivalry.

Religion and politics. The matter of the churches’ influence on political processes became even more crucial in 2014 when Russia started its military aggression against Ukraine. The majority of Ukrainian politicians would like to neutralize the influence of the Russian Orthodox Church on Ukrainian believers. “In Moscow, no one denies the fact that the religious and church frontlines of this hybrid warfare are very important. Patriarch Kirill of Moscow said that he would never let Ukraine go from under Moscow’s control. He said that the borders of the Russian Church are not subject to change. (…) The church is a broadcasting channel. In some parishes, you might be able to hear even Kremlin’s propagandist messages, or the version of them slightly adapted to our conditions by the Opposition Bloc. They used the same talking points,” said Ukrainian expert in religious studies Volodymyr Yelenskyi. This is why the trust of Ukrainian believers in the Moscow Patriarchate Church has been falling over the recent years: Patriarch Kirill of Moscow has been losing credibility as public trust in him has decreased from 44 percent in 2010 to 14,8 percent in 2017.

Patriarch Kirill of Moscow (center) and Vladimir Putin

How Ukraine’s Orthodox Churches reacted to the idea of establishing the local church. Two of Ukraine’s three Orthodox Churches support the idea of establishing the local Orthodox Church. The Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate and Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church have been long negotiating on unification. If the Constantinople Patriarchate issues the Tomos (a church decree) on autocephaly at the request of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate and of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Church, it might de-facto resolve the issue of their non-canonicity. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Moscow Patriarchate took the idea with no enthusiasm – its leader Metropolitan Onufriy did not sign the respective appeal to Bartholomew. The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate considers itself the only canonical Orthodox Church in Ukraine and thus insists that others must join it. “Canonicity” comes as Moscow Patriarchate’s best card in the negotiations.

Vladimir Putin (left) and Metropolitan Onufriy, head of Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate

Who has been criticizing Poroshenko’s initiative on establishing unified Ukrainian Orthodox Church? In addition to the Moscow Patriarchate, opposition Bloc (former Party of Regions) spoke against Poroshenko’s idea. Their main arguments are: President’s initiative is the interference of the state into the church life, President’s main motivation is publicity ahead of the campaigning, while the scenario of unification of churches is unrealistic. “I think, the Church has to decide on their own, and believers need to choose themselves which Church to attend,” one of the leaders of the Opposition Bloc faction Yuriy Boiko said in a comment to BBC.

Is this scenario realistic? Throughout the 26 years of Ukraine’s independence, no President succeeded in consolidating Orthodox Churches in Ukraine. The reason behind it is the constant resistance on the part of the church community of the Moscow Patriarchate. At the same time, President Poroshenko voiced a hope that the decision to grant autocephaly to the Ukrainian Church will be issued before the 1030th anniversary of Christianization of Kievan Rus’, namely by July 28, 2018. Many experts tend to think that Patriarch Bartholomew is likely to support the cause as the confidence expressed in Poroshenko’s statements may hint on the existing preliminary agreements. It is thus not to be ruled out that during the President’s latest visit to Patriarch Bartholomew in early April there was a certain “hint” given. “If the President is making such a statement, apparently some diplomatic church talks did take place and were successful to some extent,” said Mykola Kniazhytskyi, head of the parliamentary committee on culture and spirituality. Bartholomew might have been pushed to change his mind by the actual escalation of the situation around Russia and further isolation in the world.

The following months will show whether this scenario is to come true and how the Moscow Patriarchate will respond.