Almost 150 years later, Kazymyr Malevych remains one of the most legendary avant-garde artists in the world. His “Black Square” (which was, by the way, actually made in 4 different versions at least) still sparks passionate debates about the nature of art. Yet, despite being known for this minimalist masterpiece – or similarly complicated in its simplicity “White on White”, – he also embraced warm bright colors and shapes, the unexpected combinations of which in a way correspond to the puzzle of his life. Adored by some, denied by others, Malevych may be admired, misunderstood, questioned – but never ignored, and his influence is still all but palpable in the modern art.

And one of the things about Malevych that is especially misunderstood is his origins. Celebrated worldwide as a Russian artist, he was, in fact, of Ukrainian origin and born in Kyiv. Up until he turned 18, he lived in Ukraine and traveled throughout it, dwelling mostly in the small towns. In a way, they introduced him to traditional Ukrainian art, crafts and folklore, which were, years later, reimagined and brought back to life by Malevych in a daring, yet distinctly recognizable form. Countryside has influenced him deeply – he even tried to recreate the wall paintings from village houses, especially furnaces, back at home (and got scolded for that, so he would probably send warm regards to all the kids who still paint on the wallpapers nowadays).

With his father Severyn being an engineer in sugar production, which caused the family to travel a lot in the first place, Malevych was expected to pursue a similar career. Nevertheless, with encouragement from his mother that helped to conceal this passion for art from the dissatisfied father, he decided to focus on painting. The first professional steps in this direction were made in the Kyiv School of Art – an establishment founded by Ukrainian artist Mykola Murashko and financially supported by local patron Ivan Tereshchenko, ironically involved in sugar production Malevych was destined to delve into. His teacher was Ukrainian artist Mykola Pymonenko, internationally celebrated back in his own time.

Pymonenko and Malevych shared one important trait – both of them, at a certain point of their lives, where pushed to move from Ukraine, which was under imperial Russian rule, to the colonial center, as it was the only opportunity to build a proper career. Malevych moved to Russia and Belarus, also a part of the empire at the time, due to his father’s obligations, but seized a chance to develop his own career. Logical move in the historical circumstances, unfortunately, it lays ground for cultural appropriation that Russian government still adopts today, claiming that Malevych was a Russian artist.

His early works were a combination of cubism, futurism and expressionism – he himself would sometimes describe the style as cubofuturist. Cubofuturism united many artists Malevych would naturally grow very close to, from Ukrainians Volodymyr and Davyd Burliuk who Mayakovsky considered his teacher, to Mayakovsky himself, with whom he would later cooperate to create a daring avant-garde play.

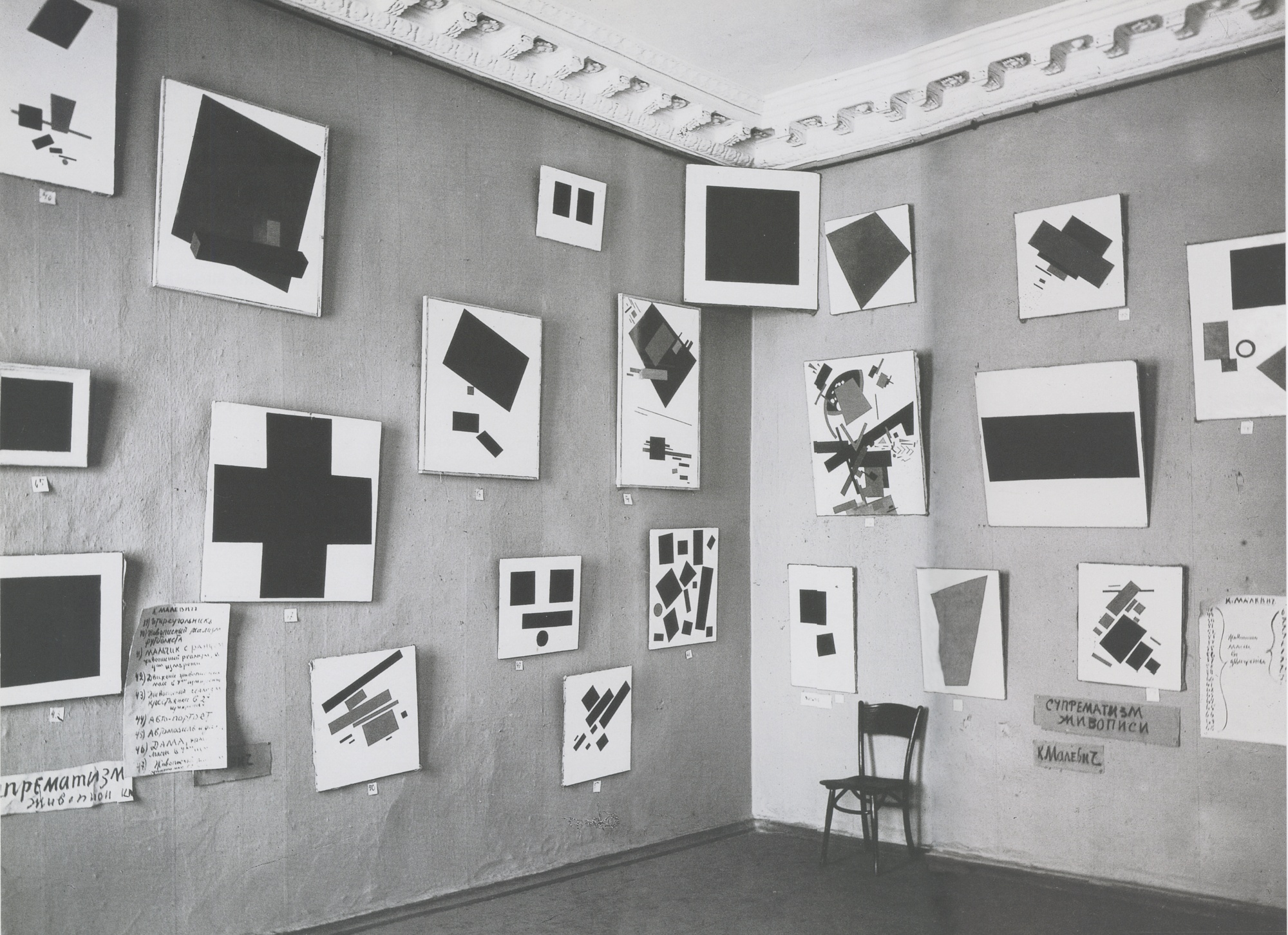

And yet the true inner discovery took place in 1915, when Kazymyr Malevych founded suprematism. Explaining it as the ultimate separation between art and the portrayal of real world, he insisted that all effort should be dedicated to color, form, texture – and we will be able to perceive the object of art as it is only after we stop trying to see fragments of reality within it. Malevych published his manifesto, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism, where he argues that “There is no longer love of little nooks, there is no longer love for which the truth of art was betrayed. The square is not a subconscious form. It is the creation of intuitive reason. The face of the new art. The square is a living, regal infant. The first step of pure creation in art.” And he has, indeed, made square regal – by exhibiting the yet unfinished “Black Square” at the The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10. Interestingly, among 39 pieces that were presented at the exhibition, the “Black Square” was positioned in a place that was traditionally reserved for the holy icons – and, in time, it became an icon of avant-garde itself.

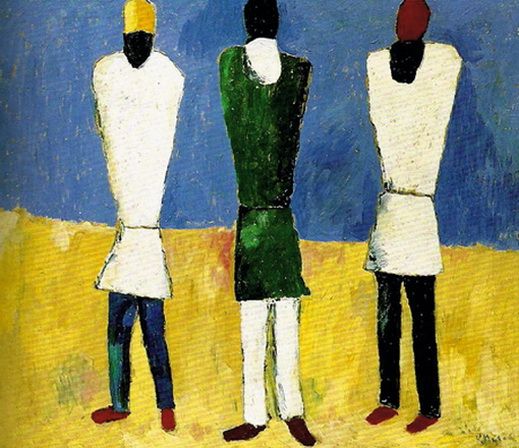

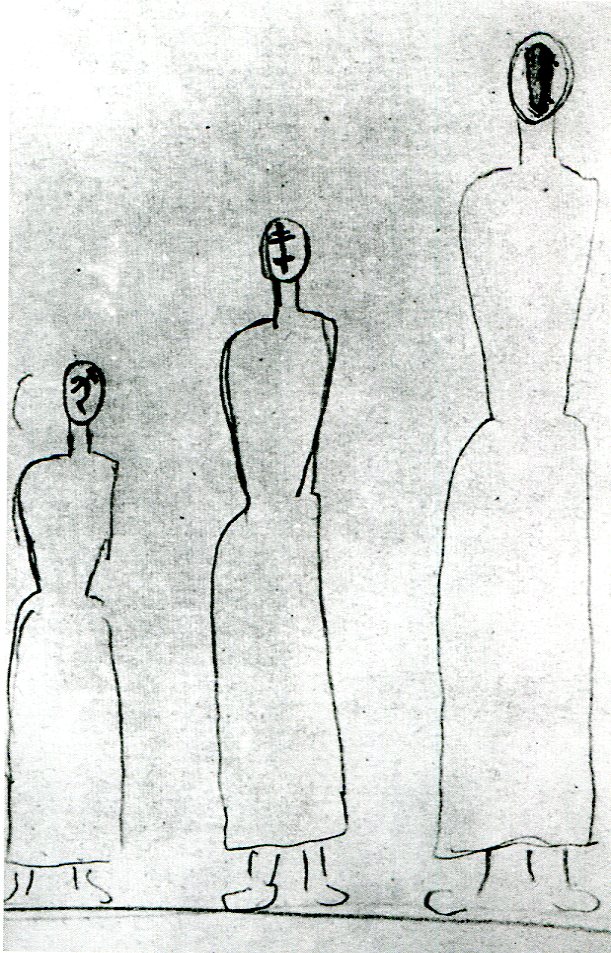

After moving from Vitebsk to then-Leningrad, Malevych returned to Kyiv in 1927, as he started feeling pressure from the authorities. He spent 3 more years in Ukraine, teaching at the Kyiv Institute of Art and writing for the Kharkiv magazine “New Generation” – an iconic supremacist outlet. Still, he was forced to leave the country once more due to the intensifying repressions of the Soviet government against Ukraine. In 1932-33, they would reach their peak with Holodomor; one of the most tragic aspects of massive death by famine, orchestrated by the central government in Moscow, was for how long this topic remained under ultimate censorship. Malevych was the only Ukrainian artist who dared to not so subtly mirror the horror in his paintings. Many of those belonging to the “peasant” series feature special hints to the tragedy, such as handless and faceless pictures of Ukrainian peasants.

Interestingly, many of the paintings touching upon this topic where dated wrong, usually with an earlier date, to avoid repercussions for the artistic protest.

Despite moving out of Ukraine – and seriously considering to start a new life in Europe, where he was deeply respected – Malevych remained under scrutiny of the Soviet secret services. He was tolerated by the regime due to his international fame, but the increasing dominance of “socialist realism” that Malevych despised left no place for avant-garde art, which was considered bourgeois. Treated with suspicion, he was on several occasions arrested by the authorities; in 1930 he was accused of being a Polish spy and questioned by NKVD. During the questioning that featured information on his nationality, Malevych allegedly insisted he was Ukrainian.

His contribution to art is global. Yet, to truly understand it – which is often quite a challenge when it comes to avant-garde! – it is essential to keep the origins in mind.

Go on a journey to discover more about Ukrainian culture in our materials within the #UkraineExplained project.

We are on this ride along with Euromaidan Press, Stopfake , Internews Ukraine, and Texty.org.ua.