Article by Yuriy Tereshchenko, historian. The Ukrainian Week

History of this period teaches that the ideals of national freedom and solidarity cannot be exchanged for any narratives of social justice and equality – regardless if it is under the slogan of ‘soil and freedom’ or a Bolshevik ‘land to the people’.

At the end of the XVIII century, after the termination of the cossack Hetmante and the Zaporizhian Sich, Ukraine was included into the overall imperial administration and state system, with the relevant unification mechanisms and governance of a self-governing police state. The conditions agreed upon in the 1654 Pereiaslav treaty, which recognised Ukraine under the protectorate of the tsar, kept the Ukrainian social order at the time – but now was brutally crushed by Russian tsarism, bringing an end to the cossack statehood.

A Ukrainian version of ‘to be or not to be’

The future of Ukraine relies on the question of whether the country would take the form of a separate national ‘organism’ or will be entirely engulfed by their northern neighbour. It wasn’t just a question of whether Ukraine would preserve its status as such, but a question of whether Ukrainians and their national identity would cease to exist or not. This is exactly what the Russian Empire was working on and the doctrine of ‘a common history of two nations’ is still proudly used by the Kremlin. In light of recent events, debates on whether or not Ukraine was a colony of Russia or had any other ties to it are senseless, despite being the battleground for social scientists. As the relationship between Ukraine and Russia does not characterise any forms of traditional colonialism such as that of the British Empire, France and Spain (when looking at historically annexed territories). Ukraine’s northern neighbour aims were unlike that of any other imperial power: to fully russify and exterminate the Ukrainian national identity. For more than 300 years the Russian empire, step by step, tried to exterminate the national culture and uniqueness of Ukraine through barbarism, thereby imposing its own social order and way of life.

For an extended time, Ukraine carried two names: Rus’ and Ukraine, its current name. The first thus became historic, while the second one was cemented as its present national reality. Such exchanges of nomenclature occurred in many other European nations. The lack of interest to grasp this, whether consciously or unconsciously, leads to a grave misunderstanding of the origins of Ukrainians as an ethnicity and often is used as a reason for xenophobic and speculative sentiment.

Read more: An Anatomy of Ruscism

Upon creating its statehood, Moscow cynically attempted to appropriate the ethnonym of Rus’ and arrived at the name of Russia (the Greek equivalent of Rus’), despite not having any historical right in doing so. Throughout many centuries, Russia manipulated through the use of the appropriated ethnonym with the aim of claiming the rich culture and socio-political heritage of the old Kyivan state.

The so-called moderniser, Peter I, knew that for the Europeanisation of Muscovy it was necessary to have a stronger basis of socio-cultural substratum, which in fact Russia did not have, but Ukraine did. Upon not having their own national, state-building and cultural achievements in common with Europe, Moscow tried to ‘borrow’ the legacy of the long-lasting civilization of Ukraine, the old Kyivan state’s tradition, culture and European recognition as such. During the reign of Peter I, Russia initiated the active propaganda of its name (i.e. Russia) and Russians as the people, instead of the old ‘Muscovy’ and ‘Muscovites’. On the orders of Peter I, Alexander Menshikov stated ‘In all the chimes, our state is printed mentioned as Moscow, not Russia, and for that reason, please warn yourself that you should print it as Russia, with regards to all scripts’. Throughout the XVIII, the age of the rise of the Russian Empire, its new false identity (based on the Kyivan Rus’) was established on political and cultural grounds. In the ‘dungeons’ of this imperial ideology, were the new works of a new and indivisible Russia, which ultimately led to centuries of exclusion for Ukrainians from their historical past of Rus’ and their subsequent russification.

The Ukrainian peasants as the bastion of national identity

Despite the various assimilative measures by the Russian Empire, the various methods used to oppress, the Ukrainians preserved a separate identity and maintained clear memory of their historical origins. A very important factor that helped preserve this identity was peasant Ukraine, which sustained itself on the generational passing of materialist and spiritual traditions. Peasant Ukraine, which had its origins in the earliest agricultural civilisations, created a solid and durable framework for national identity and existence, despite the tragic historical events which continued to this day.

Ukrainian peasantry was significantly different to that of Russia’s – in terms of land use, being essentially part of a pan-European system for a long time. Similarly, the rule of law, distribution of labour, lifestyle, social psychology and many other fields were in contrast to that of Russia’s. The underlying socio-economic difference of Ukraine was the wide use of local yard land (while Russia was predominantly known for communal land usage).

The centralism of the Russian Empire, despite its efforts, failed to fill the void between ‘communal Russia’ and the ‘yard land Ukraine’. Bolshevism was more ‘succesful’ in this regard, which drove Ukrainian villagers in to collective farming through genocide, in order to overcome the various forms of Ukrainian resistance against assimilation. However, despite the downfall of national statehood, peasant Ukraine preserved its usual way of life – the striving to tame new farmland, which eventually led to a relative success for Ukrainian geopolitical aims of developing farmland on the Black and Azov sea coast.

Read more: In the hands of criminals, history is a deadly weapon

In its natural reaction of resistance against Russian centralism, peasant Ukraine resorted to different forms of resistance such as violent rebellion and lynching of state appointed landlords which often happened on the national scale. In 1855, this is exactly how the cossack uprising in Kyiv came about, which engulfed 500 villages. The uprising made it clear that peasant Ukraine strongly identified with its historical past and national identity.

The worldview that was left preserved in peasant communities was a crucial component of national revival in the XIX and early XX centuries. Despite the gruesome socio-economic conditions, thanks to the conservatism of Ukrainian villagers, their dedicated spirituality, the national and historic traditions were preserved, alongside a crucial set of national values which provided hope for future Ukrainian elites, through art and other forms of resistance. Overall, Ukrainian peasantry played a crucial role in preserving national self-identification, inspiring the ‘reserves’ for future independence struggles. It was the engine of future struggles, both in terms of human as well as material and spiritual resources.

The widespread insubordination of Ukraine under imperial rule, despite the loyalty to Russian monarchy as an institution, gave birth to many iconic figures of Ukrainian resistance. ‘I haven’t found a single person in Little Russia [Ukraine], who spoke well of Russia, everyone expressed opposition spiritually’ as described by Alexander Mikhailovsky-Danilevsky (a Russian general) after visiting Ukraine in 1824.

The same kind of observations have been made by many other visitors, who described life in Ukraine in similar ways. One such observer was a German geographer and adventurer Johann Georg Kohl, who visited Ukraine in 1841. ‘The resentment of the people of Little Russians to Greater Russia was so strong, that it could be described as national hatred’ he stated. He concluded that the Ukrainian nobility preserved much of its independence: ‘In many households, there are portraits of Khmelnytsky, Mazepa, Skoropadsky as well as preserved scripts which recollect the events of that era’. Kohl observed an important role of the nobility in the everyday life of Ukrainians in the XIX century. He stated: ‘Ukrainians have their own language, their own historical viewpoint, and rarely associate themselves with their Muscovian rulers…It can be said that their national roots originate from provincial nobility, which is established in villages and is the main driver of political movements’. The German observed phenomena that the future Ukrainian intelligentsia did not want to acknowledge in the XIX century.

Provincial Nobility

A strata of Ukrainian nobility entailed with Ukrainian peasantry succeeded in preserving its language, religion, traditions and their original forms of social life. The duration of this process of preservation stayed throughout the entire XIX century, up until the turmoil of 1917-21. Throughout the first decades of the XIX century, after losing the previous way of social and cultural life, the Ukrainian cossack military elite, despite accepting the external influence of Russia, preserved many of its traditional lifestyles. This group especially, can be considered as the most active player in the national revival of Ukraine, as it encapsulated the social order and provided further means of expression for the future. The descendants of cossack officers were the backbone of Ukrainian resistance groups, where political issues were discussed as well as the desire to reinstate the cossack hetmanate – the revival of its previous might and its traditional institutional forms. Such circles were present in Novhorod-Siverskyi, Chernihiv, Poltava and Kyiv. Sometimes they formed among noble estates, such as the Kapnisty nobles in Obukhivka or the Malyshevsky’s in Ponurivka. The descendants of the old Hetmanate were concentrated around a sympathiser of Ukrainian traditions Mykola Repin, who was married to the grandson of Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky.

Among this circle, one could find Vasyl Tarnovsky, Vasyl Lukashevych, Semen Kochubey and Petro Kapnist. Mykola Repin also kept close ties with Vasyl Poletyka, Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko and Petro Hulak-Artemovsky. It is within these circles where the thought of a new idea was born on a potential new Hetmanate with Repin in charge. Other nobles such as Kapnist, Lukyanovych, Tarnovsky, Myklashevsky, Sherevytski families, which took part in the greater Russian opposition movements (they were a significant force in the Society of the United Slavs and the Decembrists), also spread a Ukraine-centric independence element into the minds of the other opposition figures of Russia.

The Ukrainian nobility was also the main partaker of Ukrainian literature at the time. The writers of romance-types of literature in the 20-40 years of the XIX century which were in fact the voices of Ukrainian spirituality, more often than not belonged to the dynasties of Ukrainian cossack officers, which played an important role in the era of the Hetmanate. They became the horsemen of this romanticism, which went hand in hand with the revival of national identities across Europe. It is on this basis, that the formation of rebellious moods against the imperial centrism brought by Russia took place.

Read more: “This War was Unavoidable”: Russian Colonialism and the Self-Deception of the West

An objective observation of the national reality of Ukraine in the XIX century, the position and role played by the Ukrainian nobility and elite, strongly echoes Vyacheslav Lypynsky’s later assessment of the class of the hereditary landowners and their contribution to the socio-political and cultural movement in Ukraine. Lypynsky, as the leader of the Ukrainian conservative movement, often criticised national democrats for their attempts to exclude aristocracy from the revival process. He emphasised the importance and the creative role of the Ukrainian nobility and landowners, which were fundamental to the political and cultural revival of the Ukrainians in the XIX century.

Some of the names that come up in this circle, as mentioned by Lypynsky are: Yevhen Hrebinka, both Gogols, Mykola Markovych (Markevich), Oleks Storozhenko, Hryhoriy Kvitka-Osnovyanenko, Ambrose Metlynsky, Panteleimon Kulish, Mykola Kostomarov, Vasyl Bilozersky, Mykhailo Maksymovych, Oleksandr Lazaretevsky, Oleksandr Lazaretensky, Pavlo (Marko Vovchok), Panas Rudchenko (Myrny), Oleksandr Konysky, Mykhailo Drahomanov, Borys Hrinchenko, Mykhailo Starytsky, Lesya Ukrainka (Kosach), Mykola Lysenko and more. In addition to this list of descendants of cossack-affiliated nobility, Lypynsky adds a list of polonised families of nobility, that were an essential part of Ukrainian social, scientific and cultural work: Zorian Khodakovsky, Tomasz Olizarowski, Tymko Padur, Mykhailo Tchaikovsky, Spiridon Ostashevsky, Anton Shashkevych, Pavlyn Sventsitsky, Konstantin Mykhalchuk, Borys Poznansky, Yosyp Yurkevich, Volodymyr Antonovych, Tadey Rylsky and more. Lypynsky further emphasises that it was at the cost of the so-called ‘landowner bourgeoisie’ that the Ukrainian Scientific Society was founded upon in Lviv (the founders were Yeizaveta Myloradovych and Mykhaylo Zhuchenko). Likewise, the Department of the Geographical Society and the Archaeological Commission in Kyiv, the History Museum of Bogdan Khanenko in Kyiv, and the National Foundation Museum of Sheptytsky in Lviv.

A close and lengthy alliance of Ukrainian nobility with its peasantry, a lengthy experience of economic cooperation, united through similarities in lifestyles, revived hopes of a future of national solidarity and identity.

Brotherhood of Saint Cyril and Methodius

In January of 1846, the Brotherhood of Saint Cyril and Methodius was founded. It was a secret society, which set the aim of promoting Ukrainian independence and a new social order under which Ukrainian culture would flourish. The absence of members that were related to the nobility, major landowners and aristocrats while being dominated by smaller officials, students and other intelligentsia meant that there was a major shift in the independence movement and its social foundation.

Christian principles of justice were subsequently a basis for envisioning historical processes – equality and the common good, which were in opposition to the tyrannical regime of Russia at the time. The Brotherhood of Saint Cyril and Methodius aimed to eliminate serfdom, governance in its form as it was, privileges of the imperial nobility and the security of civil freedom. In their envisioned community of liberated Slavs, Ukraine was to play a key role in a new federation of peoples, under the wing of a united Slavic church.

The Brotherhood of Saint Cyril and Methodius was a new beginning of Ukrainian political movement, an engine to future independence struggles and political thought. The most prominent representative of the society was Mykola Kostomarov, who became the head of Ukranian historiography. The brotherhood itself was influenced by western European ideas of romanticism as well as existing historical examples of slavic national revivals as seen in Adam Mickiewicz’s ‘The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage’. Standing firm on the issue of a separate Ukrainian ethnicity and nation and its own path of development, most of the members of the brotherhood were sceptical of the state actions of their own aristocratic elite and therefore focused more on cultural and educational tasks. One could see such tasks in the works of Panteleimon Kulish, who equated the concept of government with the concept of truth – in his critical view of Ukrainian nobility, he deemed the elite, hetmanate and cossack officers and their actions as statesmen as untrue. Despite the importance of Kulish’s work in the spiritual and cultural sphere as a form of national revival, a major flaw of his view was that he failed to outline the importance of a new substrata of Ukrainian elites which would work for a national revival and Ukrainian statehood itself.

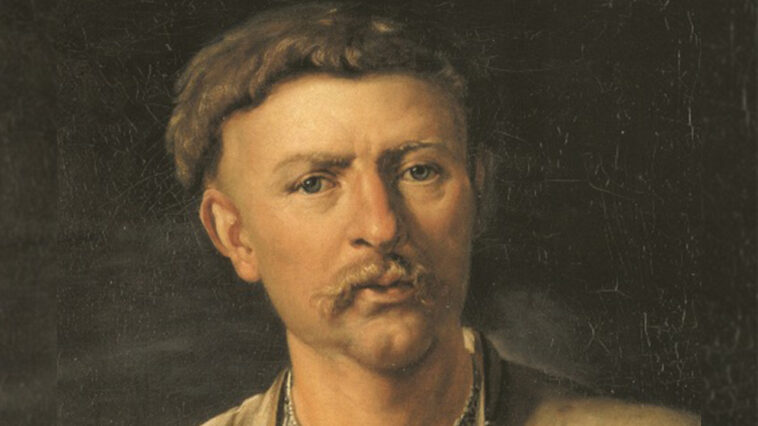

Taras Shevchenko

Another major socio-political role was played by Taras Shevchenko. His creative genius encompassed the necessity of solidarity of all social classes for a broader national revival and liberation of Ukraine and not that of a single social class or elite.

Upon the liquidation of Ukraine’s autonomy, Russian ‘reformers’ aimed for full assimilation and the disintegration of Ukrainian national elites and spiritual leaders from the rest of its people. A large chunk of the descendants of cossack elite was transformed into Russian nobility – ‘slaves with cockades on their foreheads’ as described by Shevchenko. However, this transformation was not absolute and irreversible for many aristocratic families. It is thanks to the close connections to this nobility that Shevchenko himself attributes his enlightenment to his worldview. Travelling through Ukraine, he connected with many descendants of the cossack Hetmanate and nobility, which deliberately and strongly represented Ukrainian national and cultural traditions at the time, emphatically echoing the days of the Hetmanate. It is enough to mention the following list of names who were representatives of left-bank Ukraine’s landowner cossack descendants: father and son Tarnowski, Hryhoriy Galagan, father and son Markovych (Markevych), Andriy Lyzohub, Oleksiy Kapnist, son of the famous Vasyl Kapnist (who were active members of the socio-political and cultural movement in line with Shevchenko himself). Moreover, Shevchenko’s poetic ‘Will we experience another Washington with his rule of law, yes we will, one day’ conceptualises Ukrainian opposition leaders with Vasyl Kapnist up front, which oriented themselves on the basis of American ‘separatism’ (against the English). American aristocratic opposition to England chose the path of armed resistance against English rule and ultimately succeeded by gaining independence, while maintaining its internal social dominion. For some time, Ukrainian aristocracy was somewhat successful in doing a similar feat with the support of Prussia. It is quite possible that Shevchenko was aware of an older (XVII century) strategy pursued by Vasyl Kapnist and was enlightened through his exchanges with his son Oleksiy.

Read more: Our mission is to destroy Russian imperial ideology as a political discourse, and Russia as a neo-imperial expansionist state

The first point of contact between Shevchenko and Ukrainian aristocracy could be seen as early as from his time in St. Petersburg. Moreover, it was the landowner from Lokhvytsia and Lubny counties and descendant of the cossack elite Petro Martos, with which Shevchenko cooperated in the winter of 1839-40, who financed Shevchenko’s Kobzar book (1840). He then acquainted Shevchenko with poet Hryhorii Tarnowski, a famous patron and art critic, founder of the famous collection of Ukrainian antiquities in Kachanivka, which later became an instrument of the promotion of national identity for many important figures.

Shevchenko’s relationship with the supposed Ukrainian ‘nobility’ was unambiguous, as this group often had nobles with ‘cockades on their foreheads’ as mentioned before. However, those who considered their aristocracy as a form of humane justice and consistency, as a set of principled ideas and feelings were also present. According to Alexander Konysky, Shevchenko held ‘simple, warm and sincere’ relations with Hryhorii Tarnowski, Andriy Kozachkovsky, Andriy Lyzohub and many other important figures.

If the routes of the poetic glorification of the Hetmanate are based on personal accounts (for the sake of justice, it should also be said that Shevchenko was aware of other sources of the recollection of historical events such as Mykhail Chaikovsky’s ‘Vernyhora’), then the dreams of a liberated Ukraine from Russian dominance was subsequently strongly connected with the sentiment of a revived cossack Hetmanate, which was shared by various circles of Ukrainian nobility. Because of this, Shevchenko, through the voices of his poetic protagonists, expressed hopes of a revival of the traditional form of national governance: ‘And the Hetmans will be revived in golden globes’ or ‘in the steppes of Ukraine – oh my dear God – a mace shall shine!’

Overall, Shevchenko’s connection with Ukrainian aristocracy from one hand, influenced him in his work towards his ideas of national independence (which in turn formed his opinions and perspective of national revival and was not limited to the defence of the peasantry alone). From the other hand, the work of Shevchenko itself strengthened the patriotism of Ukrainian aristocracy and created a national and spiritual network for the liberation movement – regardless of the aristocracy’s social belongings. The poetic work of Shevchenko played a crucial role in the removal of the Ukrainian elite’s isolation from the rest of society, which worked against the main aim of the Russian imperial rule.

Despite the assimilative transformation of Ukrainian elites, which in turn led to their integration into the imperial system, there are many examples of some of the members of the elite resisting the imperial regime and even attempts to retain traditional lifestyles seen prior generations. It was due to Shevchenko’s efforts that the awakening of the Ukrainian nobility took place, as the elite realised the purpose of an independence struggle, alongside the introduction of Ukrainian peasantry to this struggle. As Shevchenko said it himself ‘To the dead, living, and unborn compatriots of mine, in Ukraine and outside of it…my friendly message’. Despite his initial revulsion from the inhumane behaviour of Ukrainian nobility, Shevchenko envisioned a common goal in liberating Ukraine. This was not understood by other national figures within the movement, which distanced themselves from the perceived ‘exploitative’ social classes. Shevchenko maintained his contacts with the nobility, even more so, he was in their circles all the time, trying to convey his ideas of the importance of a national movement to them (and hence restrained his negative perceptions of interclass friction). ‘Embrace the smallest brother, my brothers…’ wrote Shevchenko. Bless your children with firm hands, and kiss the cleansed with free lips’

Shevchenko’s desire to become a central figure in Ukrainian society and national unity through the building of bridges between the elite and commoners, was also visible on a more socio-cultural basis and had its own historical implications. This relative closeness of the two different social classes was encompassed by the traditional socio-economic connection between the cossack elite and the peasant landowners, which thrived after the Khmelnytsky uprising of 1648-1654. The cossack Hetmanate was an open society that integrated the nobility and peasantry alike along with their traditions.

Throughout the course of historical events in Ukraine showed that the ideals of national freedom and solidarity cannot be exchanged for any slogans (even the most appealing ones such as ‘soil and freedom’ or the Bolshevik ‘land to the peasants’). Such ideals must be protected and promoted by different social classes of a nation. This was not understood in time by many generations of Ukrainian figures (even the ones up until the times of modern Ukrainian socialist parties).