A year ago, this tiny picturesque town near Kyiv looked like a setting for a film about a carefree life. People came here to relax, take a walk in the pine forest, and gather strength for another stressful week in the capital. Now people are coming here for a different reason – to see the place where the brutal war for Ukraine’s independence has crossed the line beyond which the attempt to avenge the enemy becomes irreversible.

And where are you from?

…

?

I’ve never thought that one day it will be so difficult to pronounce the name of my city and that no one – neither an American, nor a Pole, nor a Frenchman – will need a long explanation where it is – a small spot on the map. I’ve never thought that this single word can instantly change an expression on my interlocutor face – the pupils will dilate, the smile will disappear, the eyebrows will rise:

Are you from Bucha?

And red-hot tin of the name of my hometown, where more than 1,200 people were tortured, will come to my throat. Those people’s souls are still restless, as are those who mourn the dead. I could have been among them, had I not dared to evacuate. If those monsters did not spare babies and grandparents, would they have refrained from abusing a poetess who writes in Ukrainian?

We were among the people who did not believe up to the last minute that such a brutal war may happen in Ukraine. I still wake up every morning with a heart-wrenching feeling: can there really be such an eruption of hell in the center of Europe today, in the 21st century? Will the occupier who coveted another country not stop even before cutting off women’s breasts and tearing off their nails, raping a two-month-old girl to death in front of her mother … with a spoon, politely letting cars with families who want to evacuate into a minefield and laughing as they exploded, and then shooting to kill survivors? How did this become possible? At what point of their evolution did the demonic in the people who had decided to come to us with fire and sword become so pronounced?

I am reluctant to go back to my own experience of staying in the occupied Bucha, when the house shook from incessant explosions somewhere very close by, when I daily saw with my own eyes dreadful black swirls of smoke stretching into the sky. But there’s no escaping this experience, these memories. They can no longer be taken out of the soul like graphite out of a pencil.

Our family had stayed for two weeks in the basement of our house in Bucha since the beginning of the war. It was a dire time. At first we thought that everything would soon be over and we would be able to return to the house. Our friends from the neighboring town of Irpin, where they lived on the 7th floor of a high-rise, also came to wait it out. But other people asked the friends all the time to evacuate urgently, not to linger. However, we couldn’t do it in the first days, and then it was no longer possible. The roads to our city were cut off, bridges were blown up, and people who tried to get out by car on their own were often shot, even if there were women and children. So we found ourselves cut off from the world and going somewhere was as scary as staying where we were.

Active hostilities in our city began from the first days, they were very close by. On some days and nights, the fighting continued incessantly and didn’t stop for even a second. On the second day, a huge shell – a smerch – fell on our street close to our house. Luckily, it did not explode, but got stuck in the asphalt.

My friends managed to arrange their leaving Bucha on the 10th day. Someone called them and said a car was on its way from the city and could pick them up. But they had to walk a few streets. My daughter (18 years old) went with them. They were running under fire. As soon as they left our house, electricity and phone service disappeared while gunfire and explosions intensified.

As it turned out later, they weren’t able to go far. The road to the gathering place was strewn with corpses of civilians and broken vehicles. When they arrived at their destination, a terrible battle broke out right on their street. The house where my friends and daughter found themselves was gaping with broken windows. It was freezing outside. They hid in the basement. There was almost no food or water. A total of eight adults were trapped there. They ate tinned food – some cucumbers and tomatoes. They also had ten eggs for five days and very little water. Tea was brewed in the same water in which the eggs were boiled… But they couldn’t go back either – it was incredibly dangerous.

It was a miracle that they managed to escape – they accidentally learned about a “green corridor” and set off immediately. Fortunately, they got through safely. But those who were behind them were unlucky – they were shot at by machine guns…

My son, my husband and I were in our house at that time. We didn’t know anything about the “green corridor” either, because there was no connection and the mobiles were dead. Only when we looked out, for the first time ever, we saw people moving somewhere. Soon our neighbors came out – there were 18 people with children in their basement. I rode my bike to the city center. There were several thousand people standing there – with children, dogs, cats, belongings… They were waiting for buses but Russians didn’t let the buses into the town that day.

From those who had telephone connection, I learned that it was not safe to use the “green corridor” – many cars with people were shot.

When I returned home, I hesitated for a long time – what shall I do? I had a feeling that it was safer in my own house, because home was safer and would not let us die. And if we were to die, it would be quickly … Nowhere was safe. We could die at any moment and anywhere. And where should we go? There is war everywhere. Everyone is hard up for food and money. Can we live off anyone? I hesitated. I even decided to stay with my husband, because he flatly refused to go anywhere.

However, when the next day a neighbor offered us to go with him in his car, my son and I ventured out. It took us 5 minutes to pack. We took only the essentials and left in what we were wearing.

During our stay in the basement, we heard everything – Russian Grad missiles over our heads, gunfire, and a Russian mortar attack behind private houses. We saw a neighbor’s house on fire and there was nothing we could do, because we soon found ourselves without any communication or connection with the world. And no one would have come… It was unbearable to realize that my husband was alone in that hell.

The departure was also a very critical moment. We trudged in a convoy of evacuation vehicles, having left home for the first time during the war. I felt like a snail that had its protective shell ripped off. Only a gaping wound remained. A piece of me was ripped off quickly, without painkillers. Outside the house, a black winter was dying. Dozens of burned-out houses stood in front of us. There were flattened military vehicles on the broken roads, and abandoned shot cars on the roadside. Looted shops crumpled like sheets of paper, metal walls of hangars … Dirt and ashes. And – metal, metal, metal …

I was afraid of looking back. And I could not help but look back. When I did it for the last time, I saw a small white speck of our town and a tarry smoke rising above it. It was as thick as a white speck of the town… And our whole life remained somewhere there, in that speck …

That was when I got overwhelmed with everything at once: despair, fear, realization of the extent of the tragedy of our people. I did not understand how to live. For the first time during the war, I could not stop crying. I wanted to get out of the car and go back home across the fields. But other women in the car talked me out of doing that. I did not understand where to go and what to do… Then I began to pray: “O Lord, I give myself to You. Please guide my path through life because You know better …”

We spent a night in the basement of a church in Kyiv. The next was in the children’s center in Cherkasy region, then in a hospital ward in Chernivtsi. Volunteers, acquaintances, and just caring people, took turns taking care of us. Those days were full of worry for my husband who was out of contact, for the occupied Bucha, where fighting was intense, and for my parents, who, living in Chornobayivka (Kherson region), were also under occupation, like all other relatives and friends in Kherson.

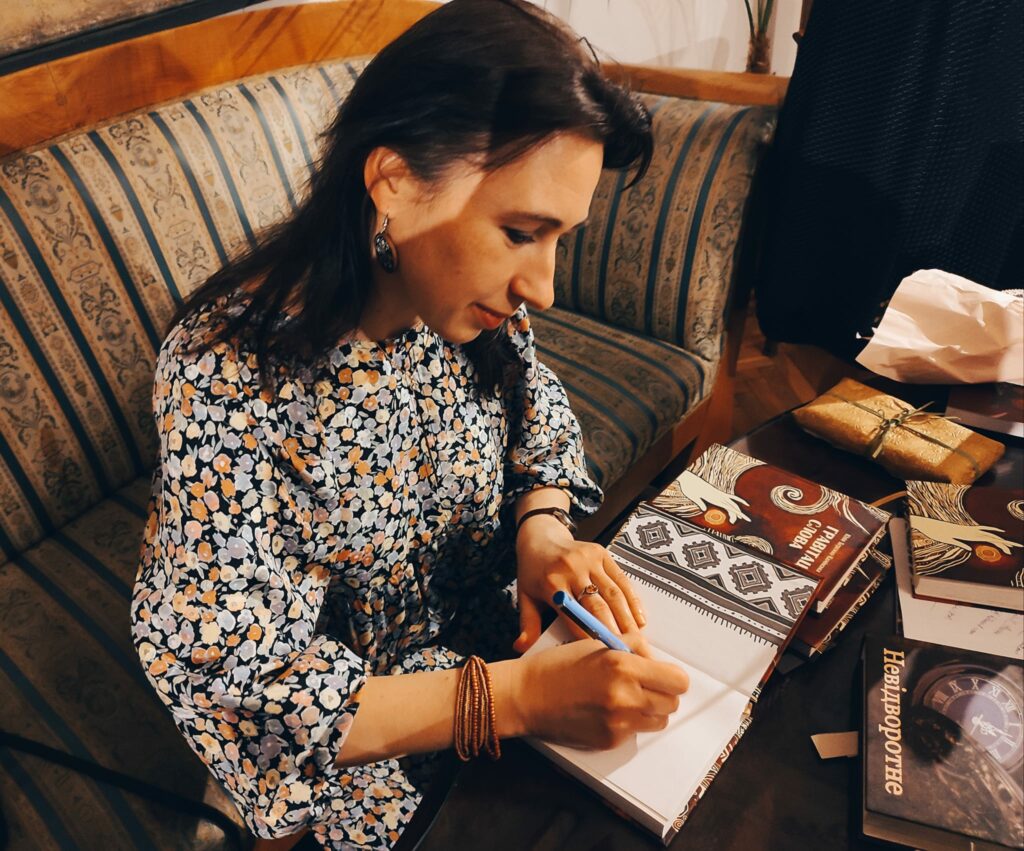

What’s now? I am learning to live in a new reality. To find a balance between excruciating pain for my country and our people and the need to do something for the future. The Lord led me to Krakow (Poland), to wonderful people, kindred spirits – also artists. They opened not only their hospitable homes but also their hearts to us, and we became very close. I am involved in our struggle for freedom through promoting Ukrainian culture, in particular literature, abroad. I have established cooperation with Polish literary organizations and hold creative meetings with Ukrainian writers who have been forced to leave Ukraine for Poland. But, like in Bucha, I wake up every day and fall asleep with a hot thought about the victorious end of the war. The only thing is that I haven’t learned to calmly pronounce the name of my town yet. Because you cannot learn it. It must be reborn from within and richly layered with the amazing good at least to balance the grief that permeates our streets today. But this time will come.

***

Звідки я — не питайте — пручається слово,

В горлі коле:

Ні проковтнути,

Ні викашляти, ні сплюнути, як отруту, —

Воно застрягає, голкасте, знову,

По колу ходить в мені, по колу,

Розтікається по жилах гарячим болем.

А замружу очі — й це слово мені — в усьому,

Починаючи з мого дому,

З обійстя мого в невикошених травах,

З магнолій, цвіт яких — на порожніх лавах,

З віконниць випалених, з огрому

Каміння, цегли, котрі — ні комин

Тепер, ні дім, ні ласкавий спомин…

Не питайте, людоньки, звідки я,

Не питайте…

На тих вулицях — ночі в вінках колючих.

На тих вулицях кожен, хто цілився, — влучив.

На тих вулицях танки асфальт місили,

Що не двір — то братська могила.

Я спокійно сказати його не в силах, —

Те слово здригається від озвучень, —

Я — із Бучі.

Yulia Berezhko-Kaminska

25.05.2022

The material was created under the joint project of Ukraine Crisis Media Center and the Estonian Center for International Development with the financial support of the US Embassy in Kyiv and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Estonia.