July 2020 was marked by at least two acts of anti-Semitism in Russian Federation, including desecration of 30 tombstones at the Jewish cemetery in Saint Petersburg. Jewish community is not the only victim of recent hate crimes: there has been a string of assaults targeting Muslims as well, with the attack on Muslim cultural center and acts of vandalism at a cemetery as well. Perhaps the most tragic case of xenophobia during the summer of 2020 has resulted in death of a 17-year old Timur Gavrilov, an Azerbaijani medical student who received 20 stab wounds – his murderer, who was detained later, confessed that he acted out of national animosity.

These cases, among many others, showcase a worrying tendency: growth of xenophobic attitudes in Russian Federation, reported by Levada Center. According to their monitoring, in 2019 ethnophobia has reached 71% – compared to 54% back in 2017. Anti-immigration sentiment is also growing, while Russian government develops controversial changes to the Concept of state migration policy, which include developing a special mobile application for immigrants containing their personal data and reflecting a so-called “social trust index”.

Majority of hate crimes (according to OSCE, 576 cases were recorded by the police in 2018, not including at least 689 incidents of extremism) are committed by individuals and not by organized groups. The situation is quite different from the one Russia had 10 years ago, when non-systemic far-right movements were much more present in the local political landscape. How did it change, why – and does it mean that there is no looming threat of ultranationalism?

Brief Overview of Russian Far-Right in 1990ies-2000ies

Radical nationalist groups were active in Russia in 1990ies. Ideologically speaking, they could be divided in two major categories: ones built on Soviet nostalgia and romanticization of Stalinist era, combining communism with ideas of Russian superiority – and ones rooted in monarchist sentiment, a manifestation of blackhundredist ultranconservatism (for example, National Patriotic Front “Memory” that originated back in the USSR and started promotion of monarchy restoration in 1994). It was also the time when neo-Eurasian ideas, primary ideologist of which is Alexandr Dugin, started gaining popularity.

The middle and second half of 1990ies were marked by the growth of skinhead groups and neo-Nazi movements, which shared aggressive racism and xenophobia. Examples include but are not limited to “National Socialist Russian Labor Party” operating in Kazan during 1994-1997 to “United Brigade-88” in Moscow, which united participants of other smaller groups akin to “Slavic Brotherhood” and “Blood and Pride”.

Activity of ultranationalists – which could be neo-Nazi, national-bolsheviks or, more often than not, those without any ideology except for violence – spiked in 2000ies and resulted in a tremendous amount of bloodshed. Extremist group “Mad Crowd” was active in 2002-2004, promoted neo-Nazism and assaulted at least 3 people before some of the representatives were arrested. Those of its members who were not, established a Battle Terrorist Organization (2003-2006), combining anti-Semitism with pagan religious views. Shults-88 (2001-2003) operated in Saint Petersburg – its leader was released in 2019 due to the partial decriminalization of provisions under which he was held in custody. It should be noted that many participants were engaged with more than one radical group. National Socialist Societywas created in 2004, had a number of regional branches, its members also explicitly shared Nazi ideology and were accused of committing 27 murders as well as 50 cases of assault. Lincoln-88, 2007, organized 2 murders and 8 assaults. White Society members, 2008, committed 4 murders.

These cases do not constitute a conclusive list. Rather, they are a demonstration of how active the ultranationalist groups were during the time. Subsequently, however, their role diminished. In 2008, Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs created a subdivision known as “Center E” – Department on Countering Extremism. It became heavily involved with countering the far-right along with Federal Security Service, which enjoyed ever-growing influence under Putin, – among other things. How Center E – and legislation on countering terrorism and extremism in general – became a tool of political repressions in Russia is a subject of separate research. The role of security services in curbing ultranationlist movements was undeniable, because Kremlin developed a two-fold strategy to deal with them. They could be eliminated – or instrumentalized.

Instrumentalization of Nationalist Movements

Putin’s coming to power coincided with growth of xenophobic sentiments in Russia, level of nationalist rhetoric in mass-media grew substantially – and much of nationalist agenda was incorporated in the new system that gradually becomes more conservative. From the active role of Russian Orthodox Church and anti-LGBT+ legislation to the recent developments in immigration field, Kremlin encompasses much of these sentiments. While bringing neo-Nazi to heel, Presidential Administration made an attempt to utilize the resource of “street politics” in the best interest of the solidifying regime. The most exemplary case is “Nashy” movement, formed in 2005 under direct patronage of then Deputy Head of Presidential Administration Vladislav Surkov. While “Nashy” portrayed themselves as “antifascists”, among other things, they often took anti-immigration stand and targeted (sometimes physically) liberal politicians and activists. In case of this movement nationalism served as ideological decorum – “Nashy” were, first and foremost, a political tool designed to prevent grassroots revolution in Russia, fear of which grew dramatically after 2004 Orange revolution in Ukraine.

While the movement essentially disintegrated by 2013, it arguably has a successor, although a less popular one, – South East Radical Block (SERB). Founded in 2014, it was focused from the very start on supporting Russian aggression against Ukraine, promoting annexation of Crimea, advocating for “Novorossiya” in South-Eastern Ukraine and taking part in attempts to seize local administrations. Interestingly enough, SERB (formally) did not even originate in Russia – it was established by Igor Beketov also known as Gosha Tarasevich, a Ukrainian national who later fled to Russian Federation, were SERB adapted an started targeting local liberals and sabotaging opposition rallies. However, it has been widely recognized that the organization is financed by Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs – and curated by that very “Center E” which is supposed to combat extremism.

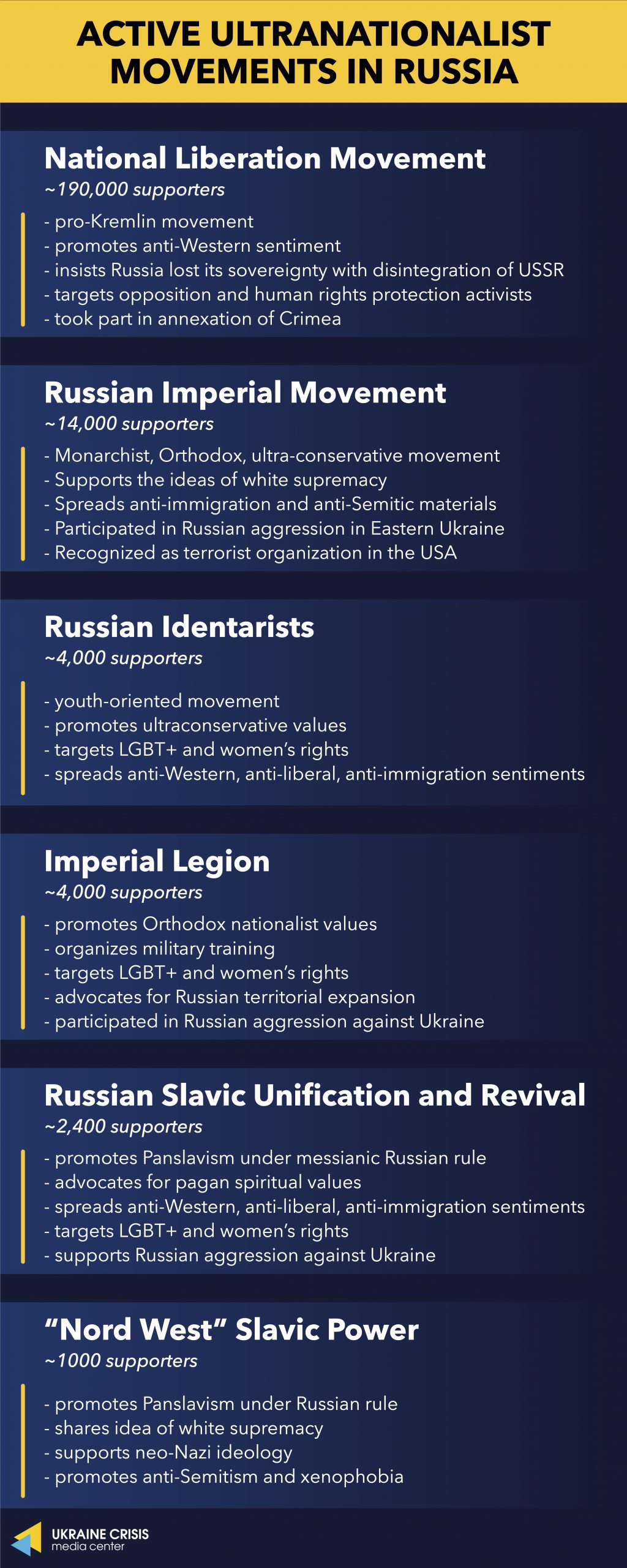

“Nashy” and “SERB” manifest a key trait of organized nationalist movements in modern Russia – majority of them may function only if they share the crucial points of Kremlin’s agenda. It stands true for those groups, from monarchist to those promoting Panslavism under Russian rule, which are still operational today.

Evidently, these movements (which do not constitute a conclusive list) share several common traits. First, they are typically anti-liberal and anti-Western. It well fits the current political framework in Russia, where Moscow consistently foments hostility towards the West. It is also useful for Kremlin that tries to discredit all possible opposition as pro-Western and reshape the whole idea of liberalism as a negative phenomenon resulting in moral decay of society (see, for example Alexey Pushkov, Chairman of the Federation Council committee on information policy, on “oppressive tolerance”).

Second, these movements tend to actively support (and even take direct part in) Russian aggression against Ukraine, which makes them a useful instrument of hybrid warfare. It involves many proxy actors, from paramilitary biker groups to representatives of Russian Orthodox Church, and looks like modern nationalist movements have also found a place for themselves in this chaos – which remains carefully controlled by Kremlin. It appears that a country which appointed itself as a vanquisher of Nazism and a leader in fighting against its revival (while accusing everyone of promoting it and supporting the European far-right at the same time), has a significant problem with ultranationalism itself.