They say that life is a road. A road that has begun and will certainly end. You can walk through a field, leaving the spring grass behind. You can go by train and watch the landscape change. And only war makes you move in sync with time.

On such days there is no time for philosophical ideas, extended reflections on what choice to make. It has already been made for you. The only goal is to run as far as you can from the roar of planes, explosions, destruction, lives taken and maimed.

Now, when you are safe and read what is happening in the occupied cities of Donbas, you understand that the instinct of self-preservation saved millions of Ukrainians. They are the force that, like a seed, will make its way out of the ground, reach for the sun, and give the necessary energy that will help dreams come true.

“All the way I covered my son, who was sitting on the car floor”

On February 24, around 5 a.m., people in Volnovakha were awakened by a powerful explosion. During the next two weeks, the town was under massive Russian shelling. Russian militants refused to negotiate any “green” and humanitarian corridors. In March, people had to leave the town under shelling, at their own risk. And after March 11, when the devastated Volnovakha was captured by the occupiers, people could leave the town only after a humiliating filtration procedure.

“I woke up early in the morning from noise and inner anxiety. Looking out the window at the glow, listening to the distant rumble of explosions, I realized that the war had begun. Friends called and said that they were leaving the town, that Kyiv was being bombed. We didn’t leave until the last moment. My husband and me looked at the crowded gas station through our apartment window and said we would not go anywhere, because our family was in Volnovakha, our home was in Volnovakha, and work was also there,” says Anna, an acrobatics coach.

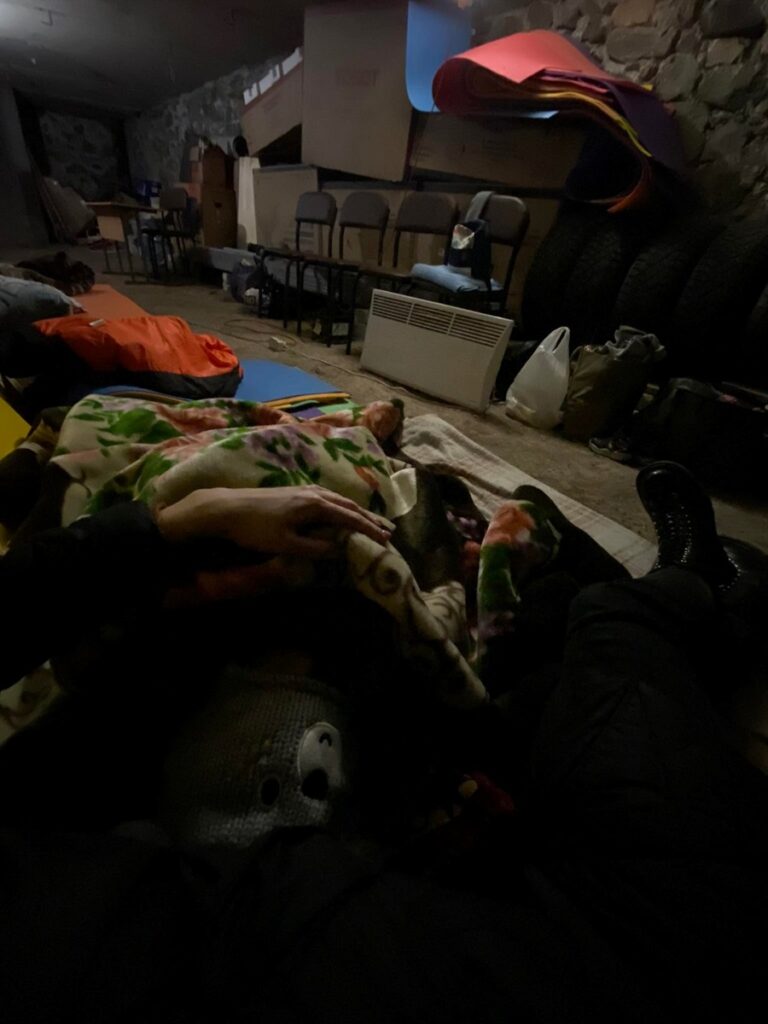

The woman collected documents, medications, the money she had saved to repair the apartment, her son’s belongings, took some food and, when the explosions became louder, the family went to her office and spent 5 days in its cold, dark basement.

“There were 11 of us, four of them children. All the food was for the children. When we ran out of food, we decided to leave. The fighting was already going on in the town, less than a kilometer away, Grads were shooting every 5 minutes,” Anna recalls. “We just got into the car and left. I don’t remember how we left. All the way I covered my son who was sitting on the car floor. We both cried.”

The road to safety was a long one. It took the family a week to get to western Ukraine. They had to sleep at strangers’ houses, in a kindergarten, and spent a lot of time in traffic jams.

“We didn’t eat anything a few days during the journey. Only on March 8, when I was far enough from the horrors of the war, I realized that all that had taken its toll and affected both my spirit and appearance. We lost a lot of weight. But that’s nothing, the main thing is that we got out and are alive,” says the woman.

Anna says that her home and gym were robbed. Everything that was not destroyed by artillery was looted by marauders. Not even children’s toys and clothing were left in the apartment.

“When light and water disappear, I start thinking about evacuation”

“At around five in the morning on February 24, I woke up – although I don’t think I’ve woken up yet – because our house was shaking. I sat up on a new comfortable bed, and my eyes were blinded by a bright glow. My daughter was sleeping in the next room,” Ksenia, an art school teacher, says.

The woman recalls sitting bewilderedly in the middle of the room and listening to constant explosions.

“I watched my husband carrying our things into the car,” Ksenia adds and says she could not realize that the war had started. She hoped naively that the explosions would stop soon, she only had to wait a little.

Ksenia says they did not pack any bug-out bags and did not discuss evacuation routes, as they didn’t believe that a full-scale invasion was possible. They thought it would be like it was in 2014, when fighting was raging outside the city, but Volnovakha lived a peaceful life: shops and hospitals were open, and the bakery continued to bake bread.

“My husband hurriedly threw things into the car: warm blankets, sleeping bags, a gas burner, a first-aid kit. Later, I started collecting my things, which are still with me,” the woman continues.

The most difficult thing in the first days of the war was to figure out where to go: “The situation changed every hour. For example, our relatives from the Zaporizhzhia region called and invited us to their place, and a few days later they were under occupation.”

The couple decided to stay in a place that was dangerous, but very close to Volnovakha, as it was so hard to leave their home like that. They consoled themselves that everything would soon be over and they would be able to return.

“First we stopped in a village in the Zaporizhzhia region. People responded to our online ad and let us live in an old house. They even gave us firewood, Ksenia says. “Information about us quickly spread through the village, so people started helping, bringing food: potatoes, lard, bread, sweets for the baby. Everyone told us how much they loved their Kinski Rozdory.”

The house in which the couple from Volnovakha settled was located in a small valley on the village outskirts at a distance of about half a kilometer to the nearest neighbors.

“We received information from a radio set which was in the house. We found out what was happening nearby when we went to the store. A few days later, the locals told us that the situation was under control and all local hunters were ready to defend the village. The woman assured us that no one would come to the village and touch us.”

A few days later, Ksenia and her daughter went to the pharmacy and realized that the situation had changed: “There were scads of soldiers in the village. The boys carried some boxes. A lot of equipment. I just started crying. I understood that they had come to defend us, but at the same time it was obvious that the russians would advance towards the village. No one knew whether our forces would hold the position and what people would have to endure.”

The next day, electricity and cell service disappeared in Kinski Rozdory, and in the evening the shelling sounds began to be heard. It was really bad without cell service, because they couldn’t even call someone from the village and find out about the situation. So the next day they deliberately went to the center of the village.

“About a week passed, and we didn’t know anything about sirens. Church bells were heard in the village, and we saw people fleeing to their basements. A tank left its hiding place.”

At 6 in the morning, Ksenia, together with her husband and daughter, were again in the car packed with blankets and stuff, which they had brought from Volnovakha: “It was scary to stay. What we feared most was that we would run into the occupiers’ checkpoint.”

Then the family came to Huliaipole, where there was no communication or electricity either. “At the hotel, we were all sent into a bomb shelter, because russians were near the town.”

Currently, Kinski Rozdory is temporarily occupied, there is no cell service in the village. Back in March, an evacuation was announced in Huliaipole, because the town was under the enemy fire.

The teacher’s family from Volnovakha lives in a relatively safe town in the Dnipropetrovsk region, but their painful experience takes its toll: “When the light and water disappear, I start thinking about evacuation.”

“Somebody squealed on me that I allegedly collaborated with the Ukrainian military and supported ‘neo-Nazis’”

Not only had the man from Volnovakha to survive the terrible shelling of the town, he also had to live in the occupied town and get out of it.

“On February 27, everything disappeared: electricity, gas, heat, mobile connection. The water supply was turned off a week before the full-scale invasion. The news pieces were passed from mouth to mouth. Most of them were russian fakes,” says Andriy (the name was changed for security reasons at his request).

According to him, about 60% of residents left Volnovakha. Most of them had a pro-Ukrainian position. The man and his family decided to leave the city when it became impossible to stay there: there was no electricity, no water, no gas. According to Andriy, it is impossible to live in that system with a pro-Ukrainian position, with love for Ukraine: they will call you “ukrop” or “neo-Nazi and either will kill you or will hand you over to the FSB.”

“Until March 12, Volnovakha residents did not have any information. Then, after the capture of the city, there were some militants of the so-called “DPR” on the square, who allowed people to use cell service and call people within the “DPR”. And who will you call if you don’t have friends who use this cell service? What is the point of calling to people in the “DPR”-controlled area? What news can they tell you? What “truth”?” the man wonders.

Andriy did not have his own vehicle, so he could not leave the town at the beginning of hostilities. He missed his chance for evacuation. When volunteers came to the bomb shelter during a lull, he was visiting his elderly relatives.

In order to get out of the temporarily occupied Volnovakha, he, like the rest of the Ukrainians, had to go through the so-called “filtration” procedure, without which it is impossible to pass any checkpoint.

“Filtration” is a piece of printed paper, with a signature and seal, where your name, surname and the fact that you are “filtered” are written down,” the man explains. “During this procedure, people are fingerprinted, photographed, their passport data are recorded, and then they are issued this filtration paper.”

“During the ”filtration” procedure, they called me in for questioning and said that somebody had squealed on methat I allegedly collaboratedwith the Ukrainian military and supported ‘neo-Nazis,’” Andriy recalls. After interrogations and searches of his home, he managed to leave the occupied Volnovakha and reach a safe place through the “DPR”: “We drove for almost three days. The worst part was crossing the border between the “DPR” and the Russian Federation, because there were few men there. What probably saved me was that I still had a Ukrainian passport despite my Donetsk residence permit. I think that if I had a “DPR” passport, I would not have been released, but sent to fight. My soul grew quiet when I crossed the border in Latvia and saw a poster “If you have witnessed crimes or aggression on the part of Russia, you can apply.” Then you realize that you are in a normal country, and that you have got out of that hellhole.”

Pavlo Yeshtokhin

July 3, 2022

Material is prepared within the project “Countering Disinformation in Southern and Eastern Ukraine” funded by the European Union.